The science behind online dating profiles

- Published

Dr Xand van Tulleken: 'Writing a profile is the hardest and most unpleasant part of online dating'

Around the world, 91 million people are on dating websites and apps. Finding "the one" among them may seem daunting - but some tips based on scientific research might help, writes Dr Xand van Tulleken.

I'm 37, and for years I've been dating in London and New York, looking for Miss Right.

Some people enjoy being single but, perhaps because I'm an identical twin, for me it's purgatory. Nonetheless I found myself single having - wrongly I suspect - prioritised work and travel for too long.

So for the BBC's Horizon, I decided to see if using a scientific approach on dating sites and apps could help boost my chances of finding a match.

My first problem was getting noticed. For me, writing a dating profile is the hardest and most unpleasant part of online dating - the idea of having to endure the kind of dreadful introspection (and accompanying self-recriminations) that would be involved in coming up with a brief description of myself was extremely unpleasant.

Added to that, I would also have to describe my "ideal partner" in some way and this has always seemed like an unappealing (and vaguely sexist) exercise in optimism and imagination.

So I took advice from a scientist at Queen Mary University, Prof Khalid Khan, who has reviewed dozens of scientific research papers on attraction and online dating. His work was undertaken not out of pure scientific curiosity but rather to help a friend of his get a girlfriend after repeated failures.

It seemed testament to a very strong friendship to me - the paper he produced was the result of a comprehensive review of vast amounts of data. His research, external made clear that some profiles work better than others (and, into the bargain, his friend was now happily loved-up thanks to his advice).

Take the test: Discover the secrets to online dating

For example, he said you should spend 70% of the space writing about yourself and 30% about what you're looking for in a partner. Studies have shown, external that profiles with this balance receive the most replies because people have more confidence to drop you a line. This seemed manageable to me.

But he had other findings - women are apparently more attracted to men who demonstrate courage, bravery and a willingness to take risks rather than altruism and kindness. So much for hoping that my medical career helping people was going to be an asset.

He also advised that if you want to make people think you're funny, you have to show them not tell them. Much easier said that done.

And choose a username that starts with a letter higher in the alphabet. People seem to subconsciously match earlier initials with academic and professional success. I'd have to stop being Xand and go back to being Alex for a while.

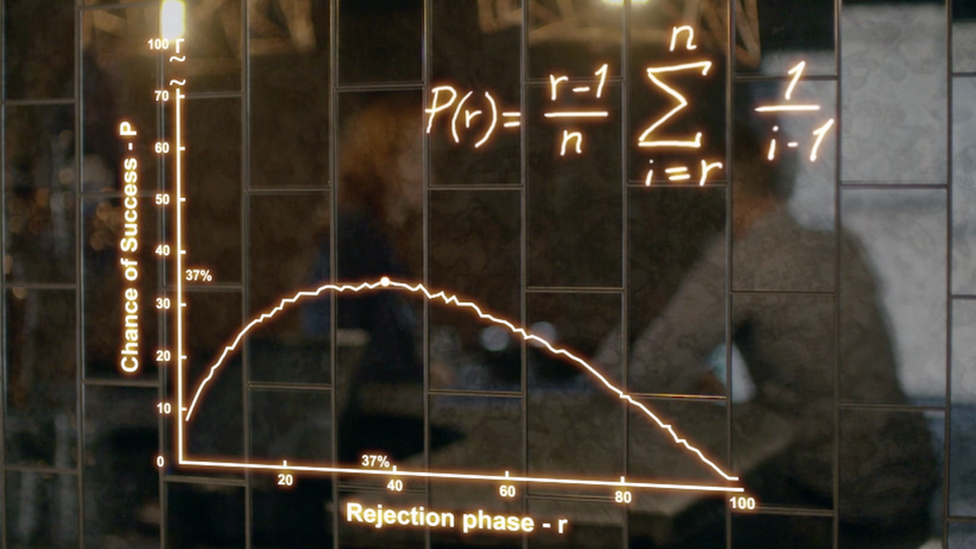

The Optimal Stopping Theory suggests a formula for using apps like Tinder

These tips were, surprisingly, extremely helpful. Don't get me wrong - writing a profile is a miserable business, but I had a few things to aim for that helped break my writer's block and pen something that I hoped was half-decent.

With my profile out there, the next problem became clear. Who should I go on a date with? With a seemingly endless pick of potential dates online, mathematician Hannah Fry showed me a strategy to try.

The Optimal Stopping Theory, external is a method that can help us arrive at the best option when sifting through many choices one after another.

I had set aside time to look at 100 women's profiles on Tinder, swiping left to reject or right to like them. My aim was to swipe right just once, to go on the best possible date.

If I picked one of the first people I saw, I could miss out on someone better later on. But if I left it too late, I might be left with Miss Wrong.

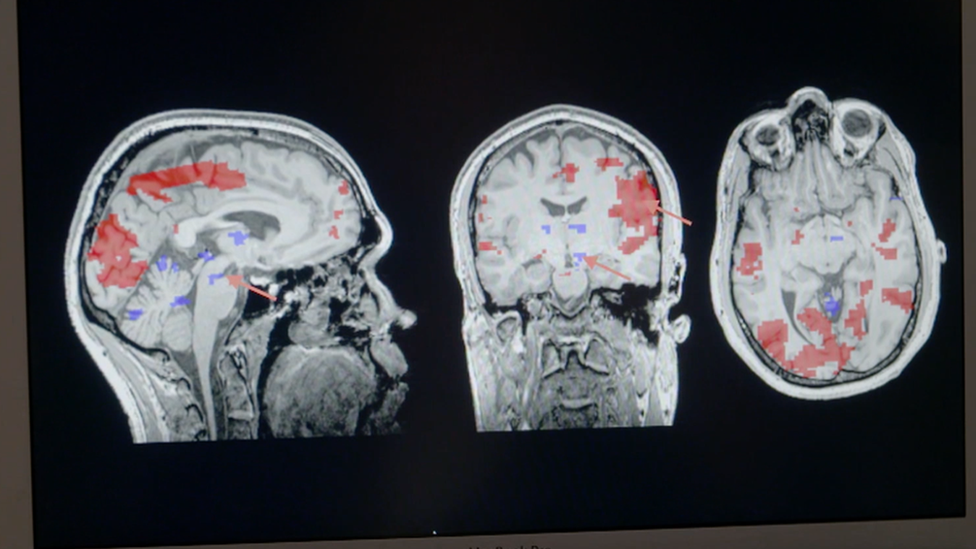

Xand's twin Chris had a scan to detect his brain activity while holding a photo of his wife

These were the results

According to an algorithm devised by mathematicians, my chance of picking the best date is highest if I reject the first 37%. I should then choose the next person that's better than all the previous ones. The odds of that person being the best of the bunch are an astonishing 37%.

I won't lie - it wasn't easy rejecting 37 women, some of whom looked pretty great. But I stuck to the rules and made contact with the next best one. And we had a nice date.

If I applied this theory to all my dates or relationships, I can start to see it makes a lot of sense.

The maths of this is spectacularly complicated, but we've probably evolved to apply a similar kind of principle ourselves. Have fun and learn things with roughly the first third of the potential relationships you could ever embark on. Then, when you have a fairly good idea of what's out there and what you're after, settle down with the next best person to come along.

But what was nice about this algorithm was that it gave me rules to follow. I had licence to reject people without feeling guilty.

And on the flip side, being rejected became much easier to stomach once I saw it not just as a depressing part of normal dating but actually as proof (again, Hannah demonstrated this a mathematical truth) that I was doing something right. You're far more likely to get the best person for you if you actively seek dates rather than waiting to be contacted. The mathematicians can prove it's better not to be a wallflower.

Once I've had a few dates with someone, I naturally want to know if it's there's anything really there. So I met Dr Helen Fisher, an anthropologist and consultant for match.com, who's found a brain scan for that.

I offered my twin brother Chris to go under her MRI scanner with a picture of his wife Dinah in hand. Thankfully for all involved, he displayed the distinctive brain profile of a person in love.

A region called the ventral tegmental area, a part of the brain's pleasure and reward circuit, was highly activated. That was paired with a deactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which controls logical reasoning. Basically being in a state that the scientists technically refer to as "passionate, romantic love" makes you not think clearly. Chris was, neurologically, a fool for love.

Interestingly, Dr Fisher also told me that simply being in a state of love doesn't guarantee you a successful relationship - because success is very subjective. And that really epitomises my experience of online dating.

It's true that it's a numbers game. And a little bit of mathematical strategy can give you the tools and confidence to play it better. But ultimately it can only deliver you people you might like and hope to give it a go with.

Additional reporting by Ellen Tsang

Watch BBC Two's Horizon: How to Find Love Online now on BBC iPlayer.

Take the test: Do you know the secret to getting a date online?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.