Viewpoint: The pioneering women of the BBC's early years

- Published

Cleaners leaving the BBC's Broadcasting House in 1932

The BBC has announced that it aims to get more women into positions of authority by 2020, but what was the situation in the early years of the organisation? Dr Kate Murphy has been researching the era for a new book.

The 1920s were a time of great contrasts for working women. On the one hand the vote had been won in 1918 (for those aged over 30) and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 had removed most barriers to the professions.

On the other hand, there was entrenched discrimination such as unequal pay and enforced retirement on marriage - the Marriage Bar - in occupations such as teaching and the civil service. The adage "a woman's place is in the home" was true for most women, once they were married.

Newsreader Elizabeth Cowell listening to a recording of her voice at Maida Vale in 1936

So who were the women who came to work at the early BBC?

When it was founded at the close of 1922, broadcasting in Britain was virtually unknown. Those who arrived at Savoy Hill, the BBC's home until 1932, were part of a brand new industry, toiling together to get the first broadcast schedules on air.

Few were actual producers, most worked behind the scenes, with women providing the vital secretarial and clerical support. As one official wryly observed "the telephones never stopped ringing, the typewriters never stopped clicking, the duplicating machines duplicated for dear life".

It was the birth of broadcasting.

Sorting the post at Savoy Hill in 1930

Because the BBC was brand new there were no set employment practices, unlike teaching and the civil service, two of the most common occupations for middle-class women in the 1920s.

Radio broadcaster Ursula Eason in 1937

An unknown typist at work in 1932

In 1926, John Reith, the BBC's managing director, issued a statement declaring that women should be "on the same footing as men", with the same chances for promotion. Women were on the same salary scales as men, and there was no Marriage Bar, at least not until 1932. Even then, the BBC made allowances for exceptional women to remain on the staff list.

In 1939, the three highest earning women - Mary Somerville (director of school broadcasting), Mary Adams (television producer) and Barbara Burnham (drama producer) - were all married. Mary Somerville and Mary Adams were also both mothers.

In fact it was the announcement of Mary Somerville's pregnancy that prompted the BBC to introduce maternity leave in 1928, at a time when this was almost unheard of. She got three months on full pay, three months on half pay - and an above average pay rise on her return.

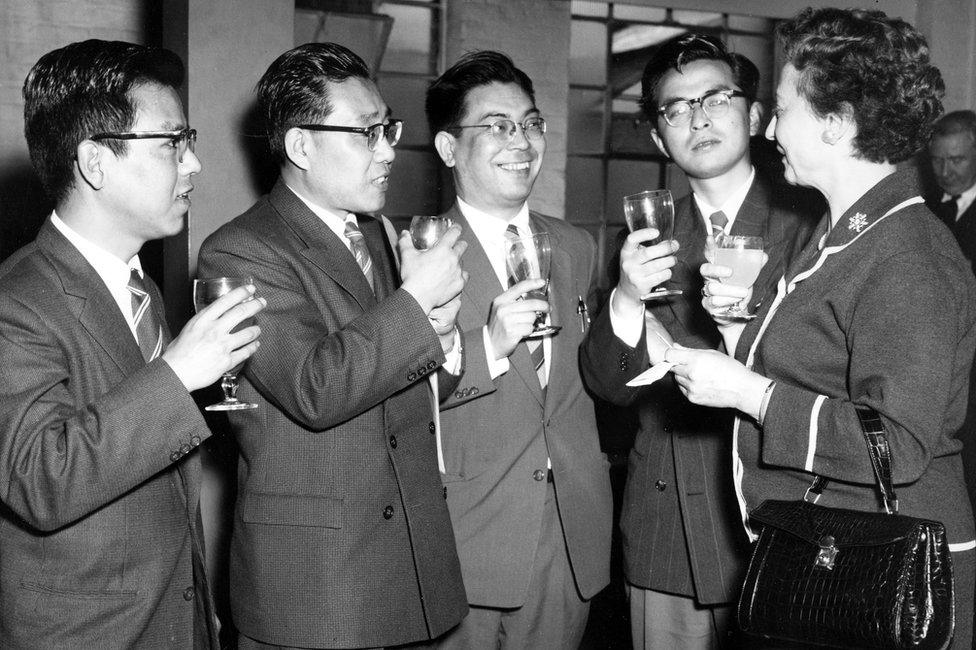

Mary Adams pictured in 1954 at a cocktail party

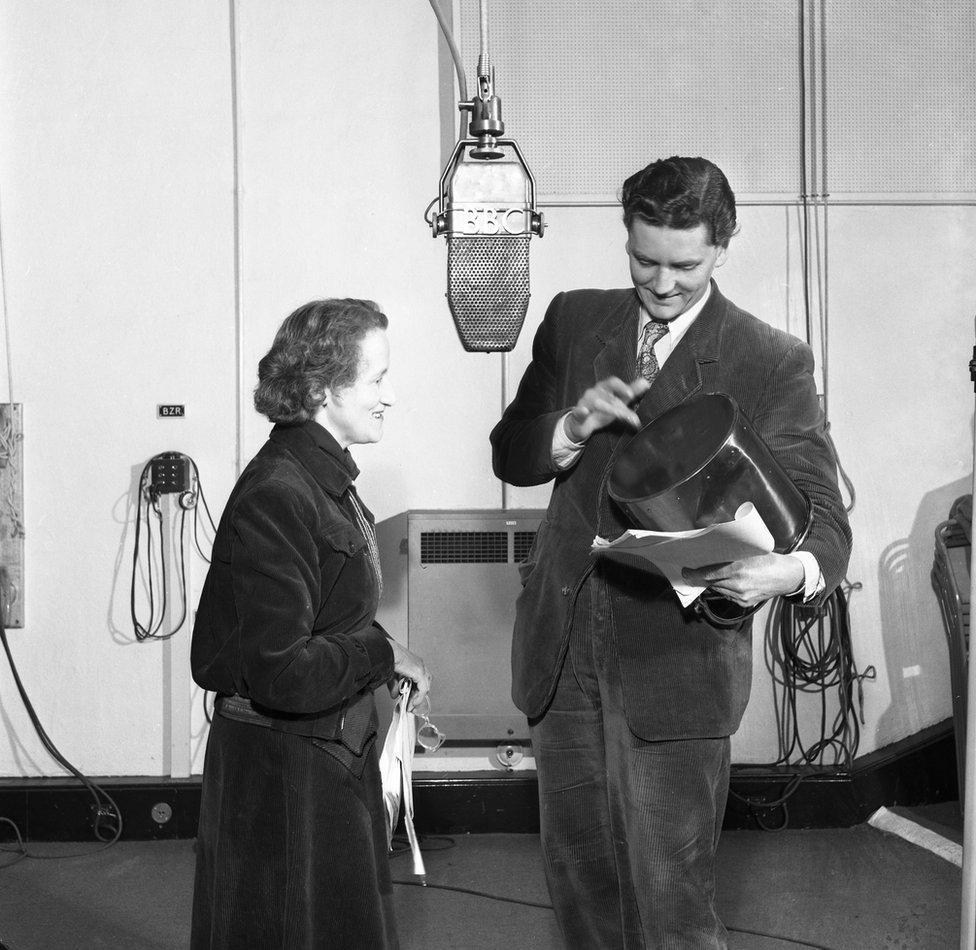

Barbara Burnham in 1952 with actor Robert Eddison

Mary Somerville and Mary Adams are just two of the colourful women who rose to significant posts at the BBC before World War Two. Others include Doris Arnold who started as a typist and became a variety star, Florence Milnes, who began the library and was its head for 33 years, Janet Adam Smith who brought modernist poetry to The Listener, Olive Shapley who pioneered social documentaries, Kathleen Lines who was responsible for all BBC photographs and Mary Hope Allen who worked on experimental radio features.

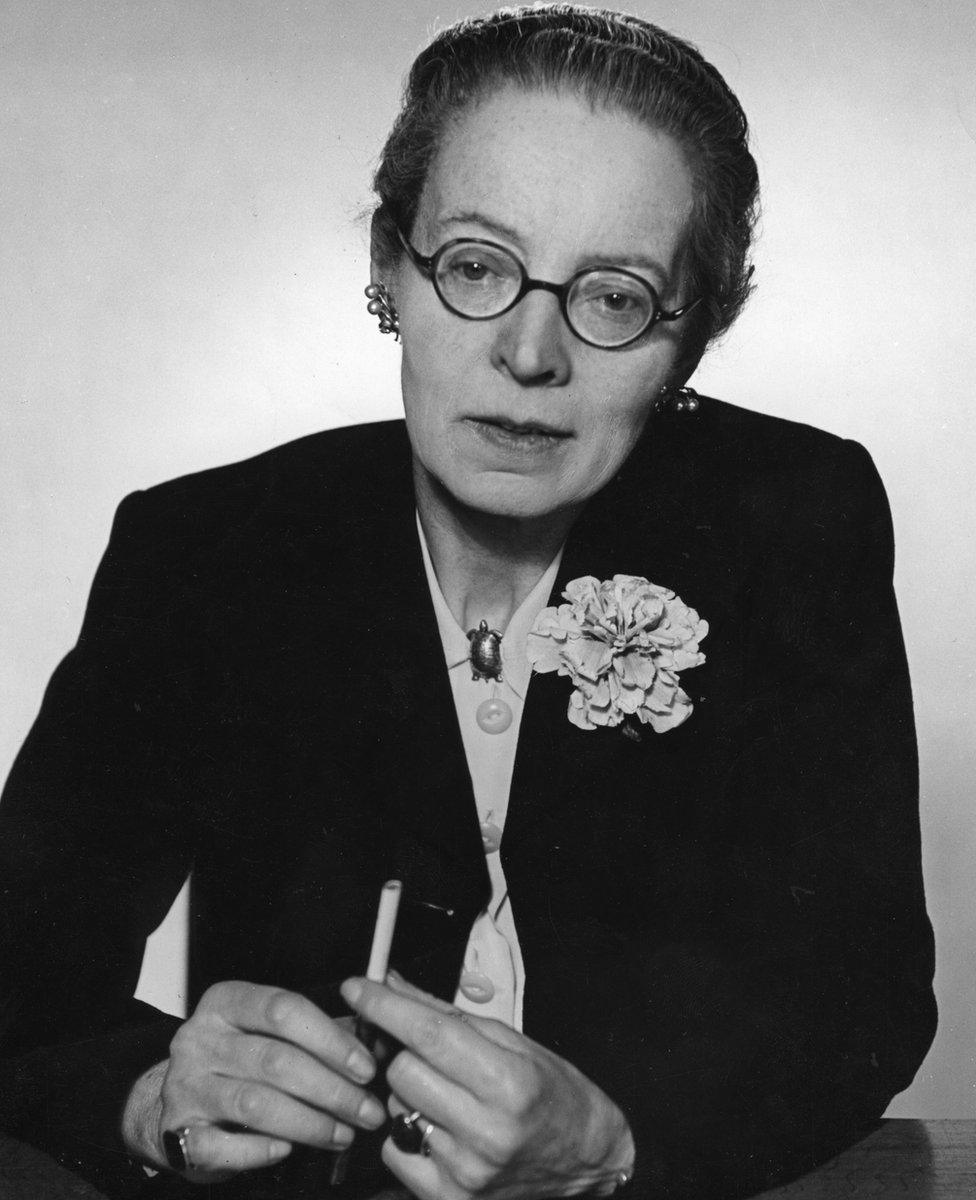

Mary Somerville pictured in 1943 was director of school broadcasting

Florence Milnes in 1937. She began the BBC's library

Janet Quigley produced Women's Hour, pictured in 1936

There was also a succession of women who produced the daily output aimed at female listeners - Ella Fitzgerald, Elise Sprott, Margery Wace and Janet Quigley. This included an early programme called Women's Hour (not to be confused with today's Woman's Hour) which, in 1924, initiated what was probably the first "listener vote". Fewer talks on domesticity was the outcome.

The Week in Westminster (still broadcast on Radio 4 today), was another talks programme aimed at women, which at first used only female MPs. It was introduced in 1929 to inform those who were newly enfranchised about the workings of parliament following the extension of the vote to all adult women (those aged 21 and over) in 1928.

Isa Benzie, pictured in 1936, was foreign director

Along with Mary Somerville, who is acknowledged as the key player in the development of school broadcasting, two other women held director-level posts in the interwar BBC. Isa Benzie started as a secretary in the Foreign Department in 1927. In 1933, as foreign director, she became its head, which included representing the BBC at the International Broadcasting Union - the sole woman in an otherwise male "club".

Hilda Matheson with Lord Hailey, a British peer, pictured in 1938

Hilda Matheson was the only woman to have been head-hunted by John Reith. In 1926 he persuaded her to leave her job as political secretary to Nancy Astor MP to take up the post of director of talks.

This was a hugely influential job and Matheson is credited with changing the way that the spoken word was delivered (she understood the importance of production) and also with enticing the big names to the wireless. Eminent individuals such as HG Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, flocked to Savoy Hill to broadcast. In 1931, Hilda Matheson famously fell out with Reith, largely over "dumbing down", and she resigned.

Miss B Everest with the studio allocation book in 1937

In 1934, in a special Women's Broadcasting Number of the Radio Times, the BBC Governor Mary Agnes Hamilton boasted that at the BBC "men and women work on a genuine basis of equal and common concern". She was right, there was an ethos of equality at the BBC. But, behind the scenes, many women did face hidden discrimination, particularly in terms of pay.

Although a few women earned more than the men they worked alongside, most earned less, partly because they were not so adept at salary negotiation, something that continues to be an issue today.

And, while John Reith might have championed some women he never dreamt of one being in his Control Board, his top executive team. The first woman on the BBC Board of Management wasn't until 1990.

Mary Hamilton in 1945

So what happened to the early BBC's enlightened attitude towards women? As it grew in size, it became ever more bureaucratic. Rather than the label of modernity and progressiveness, it wanted to be seen as part of the establishment.

The move to the grandeur of Broadcasting House in 1932, for instance, coincided with the introduction of the Marriage Bar. The increasing professionalisation of the BBC, and its growing attraction to career-minded men, perpetuated a creeping marginalisation of women.

Although they made further inroads during World War Two, post-1945 it became harder for women to get on. There were notable exceptions, like Grace Wyndham-Goldie, the executive of television, and Joanna Spicer, a TV programme planner, but it took the demands of the women's movement of the 1970s to shake the BBC out its complacent state and it wasn't until the mid-1980s that equal opportunities policies began to be put into place.

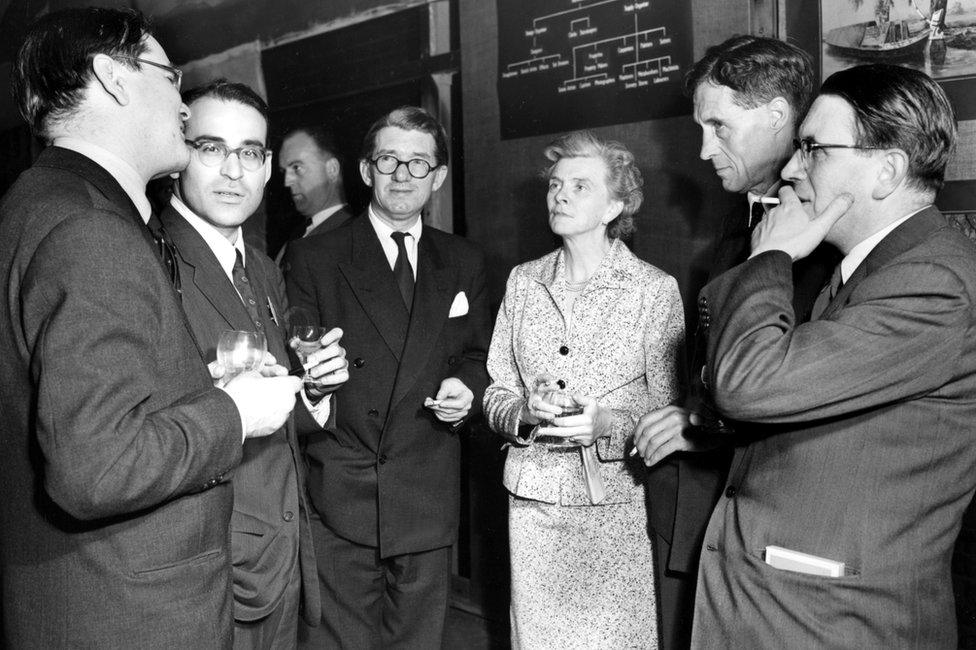

Grace Wyndham-Goldie with broadcasting visitors to the BBC in 1959

It is intriguing to speculate what the pioneering women of the 1920s and 1930s would make of the BBC today - I'm sure they'd applaud the new directive - but at least now their lost voices are finally being heard.

Kate Murphy, a lecturer at Bournemouth University, is the author of a new book, Behind the Wireless: A History of Early Women at the BBC. Listen to an interview with her on Radio 4's Woman's Hour on the iPlayer.

For more from the BBC's archives visit Rewind on Facebook, external and Twitter, external

All photographs copyright BBC Archives.