What are US university 'honour codes'?

- Published

When a young American woman told police she had been raped, her university started to investigate whether she had violated its "honour code" before the attack took place. At some US colleges even having a man in your room or drinking alcohol is an offence. What is an "honour code" and how is it supposed to work?

Madi Barney was so terrified she would be thrown out of Brigham Young University (BYU) she waited four days to tell police in the city of Provo, Utah, that she had been raped in her own flat.

"I just remember sobbing and telling the police officer I couldn't go forward because BYU was going to kick me out," Barney, 20, told the New York Times.

Her fears were borne out when she was summoned to the university weeks later. She learned her police file had been passed to university officials and they had launched an investigation into "honour code" violations.

BYU is a Mormon college, and in order to enrol there Barney had signed up to a strict code of conduct.

By committing to the honour code, students promise not to drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes or take illegal drugs. They must refrain from drinking tea or coffee or wearing skirts or shorts above knee-length. And unmarried students must not have sex - even having a member of the opposite sex in their room is a serious offence.

Barney says was told she could not register for any future classes at BYU while its inquiry into her honour code violations was pending. When she complained publicly about her treatment, several other female students said they too had been subjected to investigations after reporting sexual abuse.

Protesters stand in solidarity with rape victims on the campus of Brigham Young University

This sparked protests at the BYU and a US-wide debate about how victims of rape or sexual assault are dealt with on religiously conservative campuses.

Teresa Fishman, head of the US-based International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI), describes BYU's honour code as "an extreme case", which is "misaligned with mainstream culture". Most US universities have an honour code to uphold ideals of honesty academic fair-play, rather than a dress code or sexual abstinence, she says.

The first honour code dates back to 1736, adopted by the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. During enrolment week, entering students still gather in the university's Great Hall and pledge not to lie, cheat or steal.

Brigham Young University Honor Code

"We believe in being honest, true, chaste, benevolent, virtuous, and in doing good to all men... If there is anything virtuous, lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy, we seek after these things."

Be honest

Live a chaste and virtuous life

Obey the law and all campus policies

Use clean language

Respect others

Abstain from alcoholic beverages, tobacco, tea, coffee, and substance abuse

Participate regularly in church services

Observe dress and grooming standards

Encourage others in their commitment to comply with the Honor Code

As most of America's earliest higher education colleges were founded by religious denominations, many codes have a "distinctly moral" focus, says Fishman. When they work, they can help students feel a part of their university system and encourage a process of self-policing, she adds.

Under Princeton's honour system, in place since 1893, professors leave the room during exams - trusting students not to cheat and to report anyone who does. This system of students turning in others is a core principle of honour codes in most institutions. The accused will normally go before a panel of peers or faculty members, which then decides on a verdict and a punishment ranging from community service to suspension or complete expulsion.

Despite a number of cheating scandals at US universities in recent years, Linda Trevino, a professor of organisational behaviour and ethics at the Pennsylvania State University, says that over the past 20 years, honour codes have had a positive effect. How well they work depends on whether they become "integral to the culture", she adds.

Some universities have adopted new honour codes as they struggle with preventing students from copying information from the internet. Harvard University introduced a more formal code last year after dozens of students were suspended for cheating.

Not all US universities have an honour code. And only a handful of privately run institutions, such as BYU, use the code to demand students live in accordance with religious beliefs.

Harvard, with a motto "veritas", meaning truth, is making its students take a pledge of honesty

Liberty University, a Baptist university in Virginia, has a code of conduct called The Liberty Way, which limits students' hairstyles, clothes and any public displays of affection. Also against the rules are sexual relations "outside of a biblical ordained marriage between a natural-born man and a natural-born woman".

Other universities, including the Southern Virginia University and BYU, espouse the teachings of the Mormon church, and this is reflected in their honour codes (which apply even to students who are not active members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

BYU's strict code has created headlines in the past, with basketball star Brandon Davies expelled in 2011 for having sex with his girlfriend.

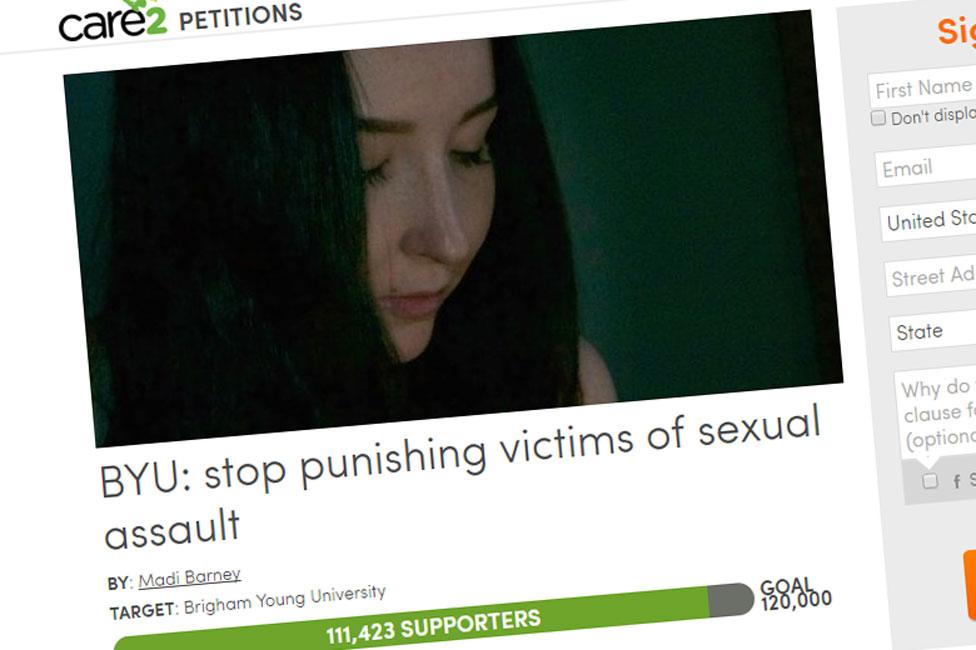

Madi Barney has started a petition calling for immunity for students who report assault

The latest news about the treatment of sexual abuse victims has stirred up an even greater controversy.

Most outsiders see disciplining a student who has already suffered sexual assault as unnecessary punishment of the victim, says Ryan Cragun, a sociologist who specialises in Mormonism at the University of Tampa.

However the university's Mormon administration separates the events - the student is not considered at fault for rape, but she is at fault for being intimate with a man, he says.

Students at BYU must regularly take part in church services

It comes down to the university interpreting its code to the letter, he says, rather than considering the overall aim to help and protect students.

BYU President Kevin Worthen has admitted a "tension" created by the honour code system and announced a review, following the protests at the university.

In a petition that has attracted more than 111,000 signatures, Madi Barney calls for immunity for students reporting attacks.

Her main objective is simply this: "I don't want anyone to have to go through what I'm experiencing."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox