Creating the world's new chess capital

- Published

Chess is a global game, enjoyed by millions around the world. For much of the 20th Century the nucleus of chess was the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. But now a new chess capital of the world is emerging - the American Midwest city of St Louis.

It's a beautiful spring evening and Chuck is sitting opposite me, outside the St Louis chess club. He's an African-American in late middle age who, during the day, runs a business selling meat. But this is where he comes after work. Between us is a beautiful inlaid chess board, on which stand elegant wood-carved pieces.

I'm forcing Chuck's king back: "Check, check, check." Then his king finds a safe haven. "Damn," I say, "I've run out of checks."

"No worries," he says, without pausing for breath and grabbing a pawn: "I'll take a credit card."

Chess is a tricky game to start with, and it's not made any easier by having to think and talk at the same time. But in speed games - blitz games, as they're called - trash-talk is all part of the competition. The aim is to outwit your opponent verbally as well as on the board. And Chuck is the King of Trash.

It's a skill shared by Maurice Ashley, the world's first black grandmaster, who grew up with chess and trash-talking in the parks of New York."The best trash-talkers blend themes on the board with themes from life, with politics, with music - they quote Shakespeare," he says. The real art, he says, is to put down your opponent - but in jest, not malice. "If you're actually insulting someone while trash-talking, you're probably not doing it right."

Find out more

Checkmate Me in St Louis is broadcast on Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 on Thursday 12 May. You can catch up on the iPlayer.

Over the past couple of years, St Louis has been in the news for all the wrong reasons. In August 2014, a white policeman shot dead a black teenager, Michael Brown, in the northern suburb of Ferguson. The riots that followed received global coverage. Here was a story about one of the most violent cities in the country, a story of racial segregation. But chess is an unusual game in that it transcends race, in a way few things in America do. "Chess has exploded in the black communities here," says Ashley.

The city's mayor, Francis Slay, wants to rebrand St Louis. If the world knows about St Louis for its black-white tension, he'd rather it was celebrated for its black and white squares. "It's a great cultural attraction. By itself it's not going to change our image. But it adds to the mix of things that make our city unique," he says.

The US Congress has officially declared the city the chess capital of the nation. In central St Louis, the plush three-storey St Louis Chess Club and Scholastic Center, external now hosts elite grandmaster tournaments - during my visit, it was the American championship.

Next door is the Kingside Diner, where instead of baseball on its giant TV screens, as in a traditional bar, you can follow chess commentary. Opposite the club is the Chess Hall of Fame, difficult to miss because at its entrance stands a 4.5m-high chess piece (a king). It offers classes, including "Toddler Tuesdays", where nought-to-three-year olds can use chess for, to quote the leaflet, "cognitive development".

Bullet chess

At the award ceremony for the US championship one of the world's best grandmasters played some fast and furious games of "bullet chess" - where each player is allocated 60 seconds at the start of the match.

Much of this has to do with one man. Rex Sinquefield, a grey-haired man in his early 70s, is sitting in the audience watching the US Chess Championship. He's in his shorts, wearing a baseball cap, and fuelling his concentration with glass after glass of Diet Coke. Sinquefield is a rich man, and he likes chess. He likes it so much he's put tens of millions of dollars into the game. No, he's not partially responsible for the renaissance in American chess, former US champion Yasser Seirawan corrects me - he's entirely responsible.

The scale of Sinquefield's wealth is unknown. He claims, a bit implausibly, that he himself has no idea. Unlike other super-rich, he's not one to brag about his bank account, though it's widely assumed he's a billionaire. The money comes from a career in finance - he created some of the first index funds, funds that are cheap to run because they simply track the performance of a stock-market index.

In Missouri, Rex is a deeply contentious figure, a looming giant of local politics -Tyrannosaurus Rex, he's been called. He pushes a radical free-market agenda and wants to abolish the state income tax. He's funded right-wing think tanks and backed selected candidates to the tune of $40m (£28m) - no-one in the state has ever given more. Missouri is the only state in the United States which has no limits to campaign donations, a freedom Sinquefield has exploited to the full. Laura Swinford of Progress Missouri, an advocacy organisation, believes his power in politics is pernicious: "I think we would all throw ticker-tape parades down the centre of the city if he would only focus on chess and his charitable donations," she says.

But Sinquefield says his political donations are small change compared to the sums he has spent on chess and other charities.

At the weekend, Sinquefield lives on a vast countryside estate. During the week, home is a handsome stone mansion, complete with an extensive art collection, just round the corner from the chess club. A solid but not expert player himself, he thinks about chess every day. He has about 18 online games going on at any one time, with opponents from around the world (he uses a pseudonym, so they have no idea who they're playing).

It's not easy to fathom what motivates his philanthropy - Sinquefield rarely speaks to the local press, and quickly deflects personal questions. But a clue is to be found a 20-minute drive from his city home - St Vincent's orphanage, where his mother sent him after his father died and where he spent much of his childhood. It was run by strict German nuns - the children slept in big dormitories, had to wash the dishes, clean the rooms and scrub the floors with steel wool. He's oddly nostalgic about his time there. "It was regimented, it taught me self-discipline," he says.

He did well at school, getting 100% in many of his tests, though he still smarts at his 97% for spelling, when he was downgraded for writing "judgement" with an "e", the British way. He went on to do graduate work at the University of Chicago, where he was taught "rational economics", and the idea that individual investors can't outwit the markets. It was this that eventually inspired him to set up index funds - the foundation of his fortune.

A regular at the St Louis chess club, eight-year-old Arjun Puri is already beating his father

But just as he credits the orphanage with strengthening his character, so he believes in the transforming power of chess. "It carries over into all aspects of a child's academic life," he says.

Around St Louis there is now an extraordinary clustering of chess activity. Three local universities offer chess scholarships, covering the tuition fees of top players. They include Webster University, which houses SPICE, the Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence. Brainy Spice herself, Susan Polgar, was the first woman in history to earn the grandmaster title by successfully competing in chess tournaments. She's built a college team at Webster that would trounce almost every national chess team in the world.

And chess is not just funded at university level. It's been introduced in after-school classes in more than 100 local schools, including all the schools in the Ferguson-Florissant School District, where the riots took place.

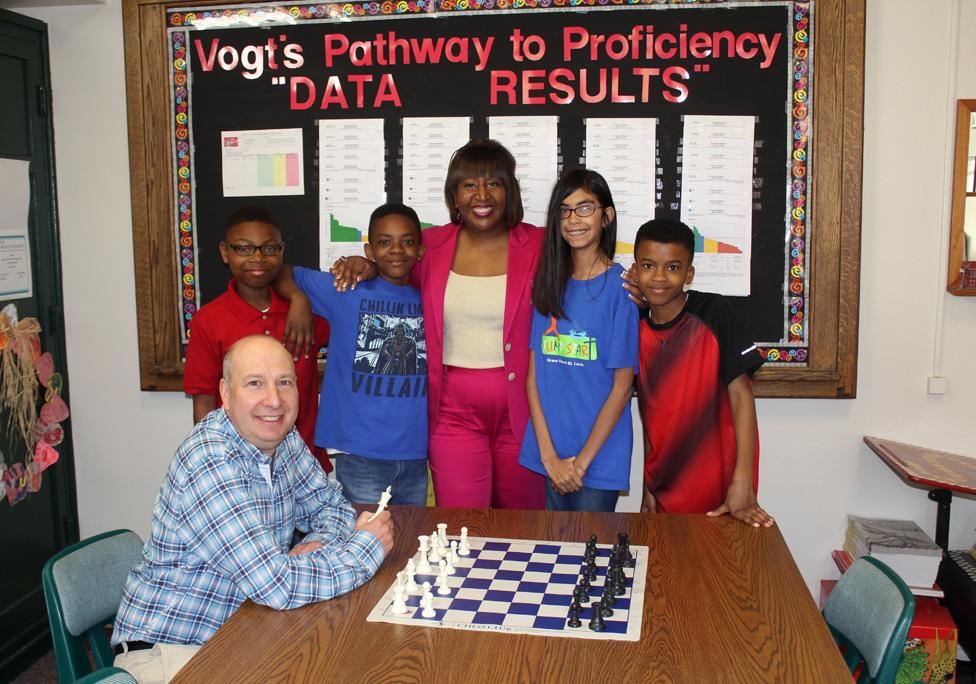

At Vogt Elementary School in Ferguson, I meet the principal, Dr Leslie Thomas-Washington. She's wearing a vivid pink trouser suit, and in the morning greets each of her students with a hug. Vogt is part of a rigorous study designed to assess whether chess really can improve attendance and test scores.

The full results won't be known for several years, but Washington says she's already noticed a difference among the children playing chess. "I've seen a dramatic change in grades. The children look at things with a more critical lens."

Back at the club, the US Chess Championship concluded with victory for Fabiano Caruana - or Fabulous Fabi, as the commentators call him.

This tournament attracted the strongest field in US chess history - the country now has three players in the top 10 in the world. They include Wesley So, who was raised in the Philippines, and Caruana, who, though born in the United States, later moved to Europe and played for Italy. Both players now compete under the Stars and Stripes. Caruana is sponsored by the St Louis Chess Club - his move back to the US is all part of the Sinquefield effect

Outside the club, the chess tables - paid for with Sinquefield money - are all occupied. I await my turn and decide to take on Chuck in another blitz game. He talks incessantly. It's the sedate game of chess - with a loud running commentary. "I'm in your house," he says, as a rook enters my half of the board. "I didn't want to break in, but you left the back door open and I'm in your house." And with that, he captures another pawn.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.