Fleeing Saddam with the Kurds

- Published

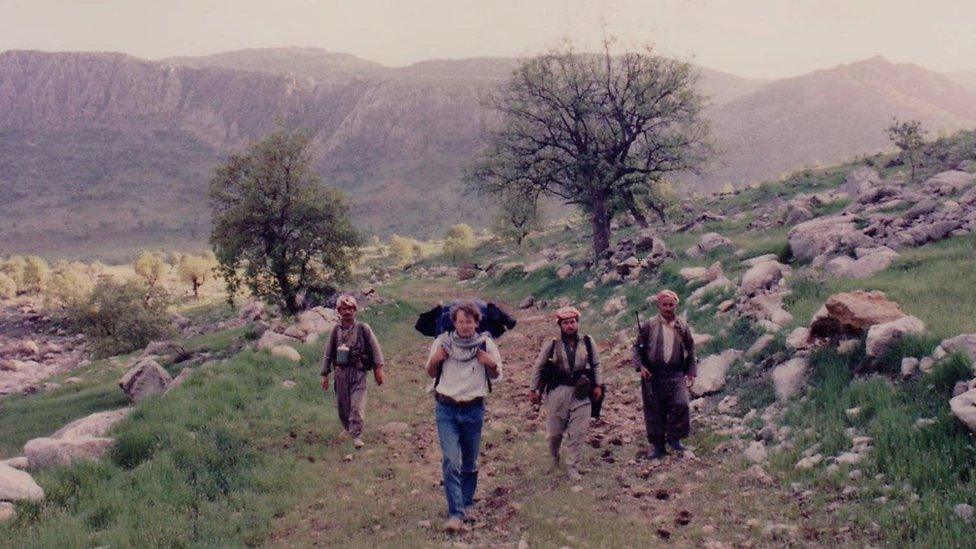

Jim Muir leaving for Turkey after six weeks with the Kurds

Twenty-five years ago, virtually the entire Kurdish population of northern Iraq fled the forces of Saddam Hussein. BBC Middle East correspondent Jim Muir, who witnessed it first hand, recalls the dramatic exodus.

I arrived in Kurdistan, crossing the swollen border river in a tiny boat, armed with the technology of the day - two notebooks, a tape recorder and four cassettes.

The Kurds had taken over the whole of the area they regard as theirs, including the big cities of Erbil, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah and Dohuk. The Iraqi army had fallen to pieces. The Kurds were jubilant - generations of struggle against the central government in Baghdad had, it seemed, suddenly been magically rewarded.

But disaster lay only days ahead. Saddam struck back, sending tanks, artillery and helicopter gunships to attack the big cities on the flatlands. A vast flood of humanity, several million strong, poured out of those cities and up into the mountains, heading for the Turkish and Iranian borders.

They travelled in every kind of vehicle you can imagine. A patient being trundled out of Dohuk on his hospital bed, still hooked up to an intravenous drip. Children being carried out of Erbil in the scoop of a bulldozer. And of course, many just walking, often barefoot, past the vast queues of stalled vehicles, stretching from the borders 9,000ft up in the mountains all the way back down to the plains.

Iraqi Kurdish refugees cross the Iraq-Iran border in April 1991

The weather was foul and freezing. Many died of hunger, exposure or dysentery. Dead children were being buried at the roadside.

While the civilians fled, the Kurdish Peshmerga guerrillas stayed behind and I witnessed several of the battles in which they pushed back Iraqi forces trying to advance into the mountains.

But the plight of the Kurds, meanwhile, had caught the world's attention. The western powers imposed a no-fly zone and a safe haven in northern Iraq so the Kurds could stay and return to their homes.

Nowadays, of course, there would have been satellite trucks and the internet, and all of this would have been transmitted live minute-by-minute.

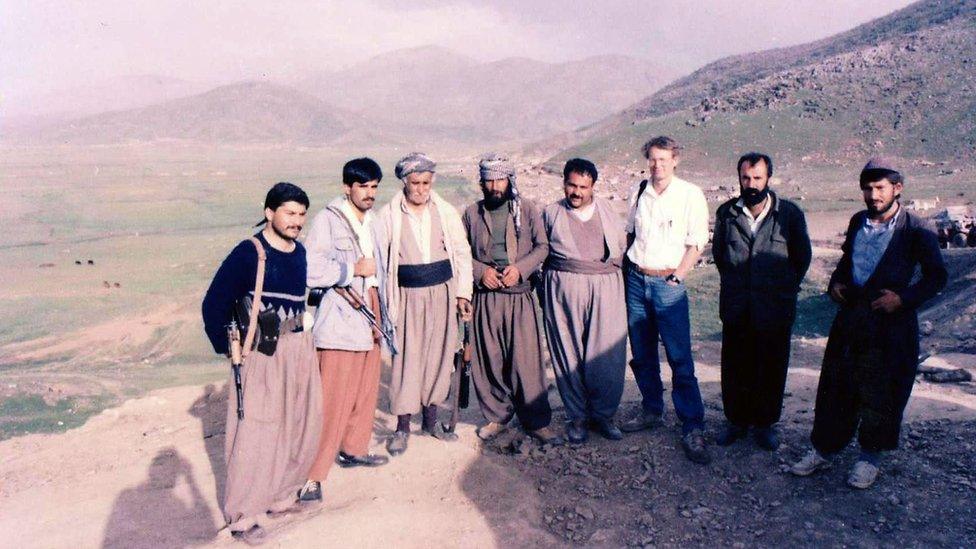

But all I could do to get the barest news out, if I was with Masoud Barzani's KDP fighters, was to shout despatches down a Peshmerga backpack military radio to an office in Damascus that somehow managed to pass them on to London - or, if I was with Jalal Talabani and his PUK, I could shout them down what may have been the only satellite phone in Iraq at the time. But, meanwhile, I was recording on my four cassettes, descriptions of what was going on, interviews, and battles.

When I eventually left, walking up through the mountains across into Turkey, I carried those unheard tapes with me. Things had, of course, moved on by then. There were new stories to cover, so those tapes remained unheard, sitting in a drawer, for 25 years, until we decided to make a programme with them.

Find out more

Jim Muir with Kurdish fighters, 1991

Listen to Iraq's Kurds: From Flight to Freedom on the BBC iPlayer

I was full of trepidation. How much of what I had experienced would be there on the tapes?

The answer was, a great deal. Many interviews with Barzani and Talabani as the story unfolded, and with another Kurdish leader, Sami Abdul Rahman, whose elderly father died as the family fled from Dohuk. A larger-than-life actor called Hama Ali, who the last time I saw him in the mountains, had lost his own wife and children in the chaos of the mass flight. Many other voices and commentaries that brought it all flooding back.

To bring the story up to date, I went back to Kurdistan a quarter of a century later to see what had happened to some of the characters.

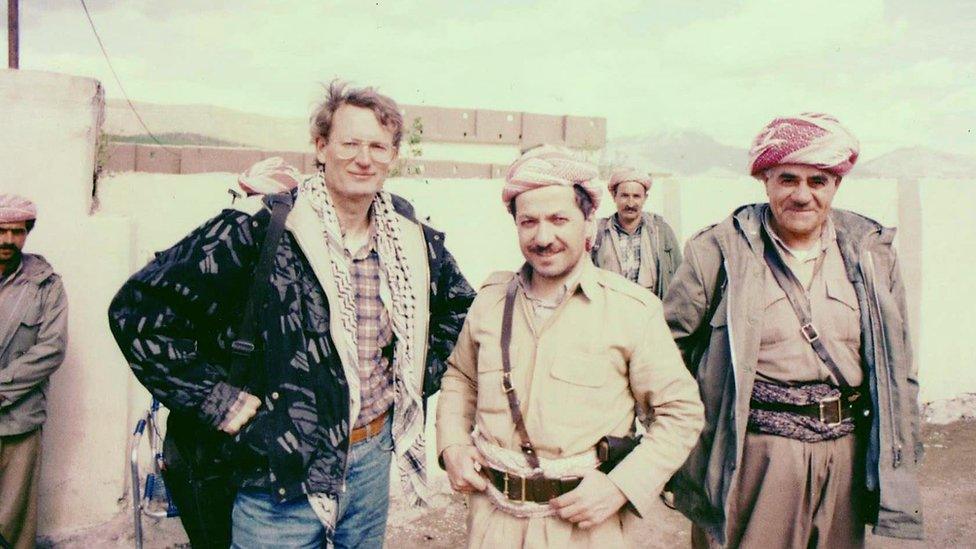

Jalal Talabani, of course, succeeded his adversary Saddam Hussein as president of all Iraq. He's now sadly handicapped after suffering a severe stroke some years ago. Masoud Barzani became president of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, and still is.

Sami Abdul Rahman, the other leader, was killed along with one of his sons by a suicide bomb attack in 2004. His name is immortalised on a huge public park in Erbil, and I interviewed his son Sirwan there.

KDF fighter Masoud Barzani (centre) is now president of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan

Hama Ali, the ebullient actor, I tracked down in Sulaymaniyah. He did find his family, and the two-month-old daughter he was so worried about is now married and about to produce his first grandchild.

But I wasn't able to find out two things. There was a badly-wounded Iraqi soldier who'd clung to life for two days among dead comrades on the battlefield and had the same deathly pallor as them. The Peshmerga put him in a car and sent him back to the government side. Did he survive?

And up in the mountains, there was a little boy, about eight, clutching a tiny suitcase containing all the possessions he had left. He'd lost his family during the exodus. What became of him?

These are things I'll never know.

Listen to From Our Own Correspondent on BBC World Service or on BBC Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 and Saturdays at 11:30. Or catch up on the BBC iPlayer or get the podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.