The secret life of a transgender airman

- Published

Transgender people are banned from serving in the US armed forces, yet an estimated 12,800 do, the vast majority in secret. Jane, a master sergeant in the Air Force, has hidden her gender identity from the military for 25 years. She hopes a policy review announced last year will allow her finally to be herself.

Jane likes to run early in the morning, really early, when the light is thin and the overnight air is still cool. A little before 5am she pulls on a light pink jersey, tucks her hair under an old US Air Force cap and heads out into the quiet, pre-dawn streets. When she runs she can forget for an hour what others think of her. She can let her mind wander and lose herself in thoughts of the future. And there's a lot to think about, she is getting ready for her life to change.

Jane is waiting for the day she can finally tell the Air Force that she's transgender. Assigned male at birth, she has served her country for 25 years as a man. She has flown in every major conflict since the first Gulf War and earned medal after medal along the way. And she loves her job, she calls it an "honour and a privilege". But it has forced her to live a double life.

There are an estimated 12,800 transgender people serving in the US military, in violation of Defense Instruction 6130.03, which prohibits what it calls "psychosexual conditions". The Department of Defense announced in October it would review the regulation and a small number of transgender service members have since come out. A handful are even openly undergoing hormone therapy. But the rules are applied inconsistently from unit to unit and thousands continue to hide their identities.

If Jane's commanders were to find out she had received treatment from a civilian doctor she would be instantly grounded, she says. She agreed to speak to the BBC on condition that the nature of her treatment, as well as her real name, were not published. But changes to her body are becoming harder and harder to disguise and her efforts to cover them up more and more exhausting.

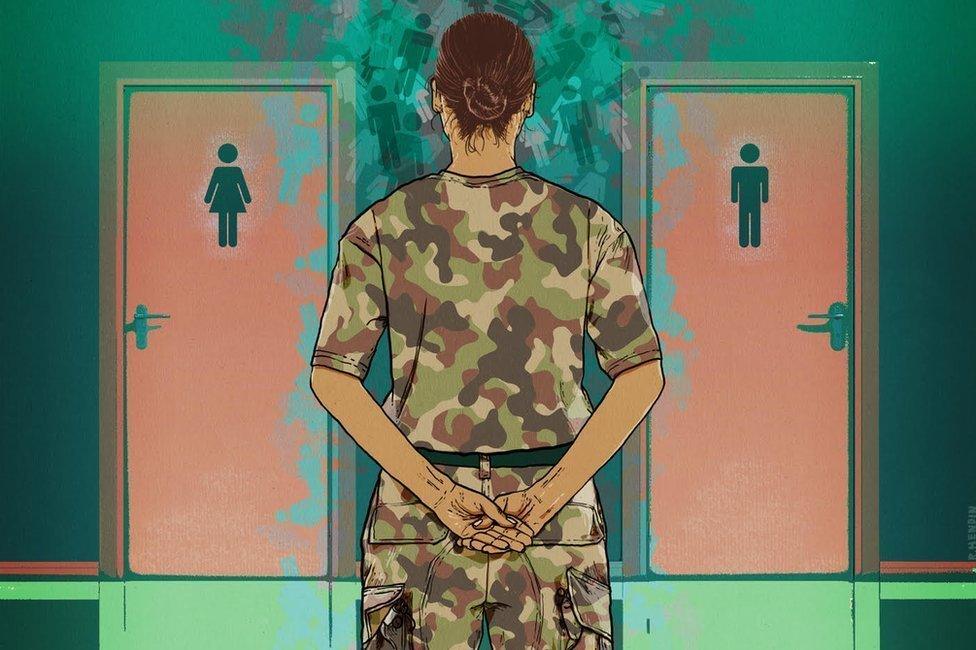

Off base, Jane is free to live and dress as she likes, with the caveat that she avoids anywhere she might run into a colleague. On base, she has to wear a man's uniform, maintain a regulation men's hairstyle and use the men's toilet.

She longs for the day she can be open with her colleagues. She longs to have the surgery that will complete her transition. But until the military changes its regulations both remain out of reach. "I don't know how much longer I can hold it back," she says. "I don't know how strong I can be."

"Picture yourself in the cockpit of an aircraft. You've got gauges, switches, dials. You need focus. But all the time you're thinking: How's my voice? How are my mannerisms? Am I doing anything to give myself away?"

At work, Jane can't afford to let her mind wander. Take a group run, for example. Leading the bunch one day, her thoughts beginning to drift, she hears a shout that snaps her back into the moment: "Hey Sergeant, you know you run like a girl!"

Suddenly she can feel eyes like pinpricks on the backs of her legs, which are completely smooth. She starts to scrutinise every movement. Then someone else, an ex-marine, sidles up alongside her. "Hey, I'm thinking you'd make a pretty good woman," he says, "so if this thing doesn't work for you, you could always go get a sex change."

Jane's voice is soft and warm but it dips a note as she remembers: "I mean, what can you say to that?" What she wants to say, to shout aloud, is "OK here's the deal! I'm transgender!" But she has too much to lose, she's too frightened of the reaction. "Especially the people in the special ops community," she says. "They are unforgiving with this sort of thing."

One member of her unit stopped speaking to her after a water survival test, which requires airmen to swim a length of a pool in full flight gear. Emerging from the water that day, drenched from head to toe, Jane anxiously scanned the area for changing rooms. There weren't any. The men would just change by the van, someone said casually. Nobody else blinked an eye, but underneath her flight suit Jane wears a sports bra and soaking wet it sticks to her skin like shrink-wrap.

"It was my worst nightmare. I went round to the other side of the van and opened the door to hide behind. I had my clothes all laid out so I could change super quick, but sure enough, as I'm trying to peel off my sports bra I look up, and one of the guys is right there." He saw, turned around, and walked off. All Jane could do was wait and prepare for the worst. "I was sure he would tell someone," she says. "I wanted to die."

Fortunately for Jane, he didn't. But what her colleagues make of her could have as much of an impact on her career as being discovered by her commanders, she says.

"They say there isn't a no-fly list but really there is. Because everybody says, 'I won't fly with this person or that person,' because they don't get along or whatever. The next thing you know I would be on everybody's no-fly list, and there would be no record of it.

"You can legislate some sort of guarantee that people are protected," she says, "but you can't legislate acceptance."

In 2011, the US military ended its controversial "don't ask, don't tell" policy which had prohibited lesbian and gay people from serving openly in the armed forces. But thousands of transgender soldiers, sailors, and airmen were left hanging, forced to continue hiding their identities.

And yet, studies suggest that transgender people are more than twice as likely as the general US population to serve in the military. A 2014 paper by the Williams Institute at the University of California found 21% of transgender people in the US have enlisted in the military compared with just 10% of the overall population. The Transgender American Veterans Association, Tava, estimates that there are about 135,000 transgender veterans.

Some argue that integrating transgender servicemen and women would damage unit cohesion, and that hormone treatment and gender reassignment surgery are incompatible with active service. But 18 countries around the world already allow trans people to serve in the military, including the UK, Canada, and Australia.

A spokesperson for the Department of Defense says integration is "a very complicated issue with health care, individual and service readiness, and cost implications".

Aaron Belkin, the director of the Palm Centre, a think tank that studies gender in the military, disagrees.

"This isn't rocket science, there is a set of best practices developed by various other organisations including the British military," he says. "On the spectrum of difficult things the US military has to do, this is at the very bottom in terms of difficulty."

Jane discovered two things about herself aged eight. One: she wanted to be a fighter pilot. Two: she was in the wrong body. The first made her a stereotypical boy in small-town USA, the second made her feel like "the weirdest kid ever". Then one day a transgender character appeared in the daytime soap Love Boat, and something clicked. "I felt so alone at that time," she says, "then I saw Love Boat and it was just earth-shattering."

For her parents, both committed Christians, the easiest thing was to pretend it wasn't happening. For Jane, the best thing was to stay quiet and hope the same. She tried to do some covert research but this was pre-internet, and where Jane grew up "they didn't exactly have stuff on this in the library". When the internet finally turned up, years later, it mostly rewarded her efforts with porn, which she was not interested in. She wanted to connect with people. More than anything though, she wanted the feelings to go away.

So, as a misfit teenager with a secret she didn't fully understand, Jane signed up. "I thought if I just do basic military training it will go away, but it didn't," she says. "Then I thought maybe when I qualify it will go away, but it didn't. So I thought OK, maybe if I go into a dangerous career field it will go away..." Getting a flying position was a long shot, she says - "spitting in the wind" - but she got one. She was elated. It didn't go away.

In 1988, a former military psychiatrist, George R Brown, coined an expression, "flight into hypermasculinity", to describe the counter-intuitive attraction of the military for transgender people. "For some, the mere act of enlisting was not enough," he wrote, outlining the cases of several trans fighter pilots. "The patients deliberately chose the path of greatest danger while in the service."

Amanda Kerri, an army veteran who grew up in small-town Mississippi - "where there was not exactly a lot of understanding about what transgender was" - and transitioned from male-to-female after leaving the army, remembers feeling that she had to "double down on being tough and macho". So, aged just 17, armed with an underage waiver signed by her parents, she joined the Mississippi National Guard.

But when the unwanted feelings don't disappear, a macho environment can become a hostile one, especially for transgender women. "If you look at the articles that have been published about trans people serving openly, most or all are about female-to-male," Kerri says. "They can be one of the guys, one of the dudes."

Kerri, who retired from the army in 2003 and now writes about LGBT issues, says coming out while she was serving would have been inconceivable - "the culture back then was not conducive at all".

Now, depending on where, and perhaps who you are, it can be. About 80 active service members are thought to have come out as transgender, although there are no reliable figures. "I'll tell you, that takes some incredible courage," says Kerri. "It's ballsy as hell."

For years, Patricia King was terrified of telling even one person the most important thing about herself. Then one day last year she made a decision: she would tell someone new every day for 100 days. "And I didn't even have that many friends!" says Trish, or Staff Sgt King as she is known in the infantry.

So that's how Staff Sgt King ended up telling her new hairdresser one day that she was transgender. Three months later, after she'd told 100 people, chucked out all her male clothes and deleted her old Facebook account, she was ready to tell the army.

Telling the infantry, which until a few months ago didn't even accept women, that you are really a woman, is not like telling your new hairdresser. Especially if you're the first person to ever do so. But King's immediate superiors were sympathetic, she says, and so were many of her peers. Her military doctor even took over the provision of her hormone treatment.

In that sense, King has been fortunate. But now, after 16 years in service and three deployments to Afghanistan, she is in limbo, forced to continue serving as a male soldier even as she continues to transform her body.

Staff Sgt Patricia King was the first openly transgender woman in the infantry

Her new existence as a woman in a man's world can be a lonely one, she says — "How can I put this, It's 50,000 men and me." And there is "absolutely" sexism against trans women, she adds. Among the things she has heard called out on group runs:

"Hey there's that Bruce Jenner dude."

"There's that dude that thinks he's a chick."

"Hey shemale!"

And worst of all, she says: "Tranny".

"There is an ease in accepting trans men but a much larger challenge in accepting trans women," she says. "It comes down to a cultural misogyny maybe. The concept that you would want to give up male privilege and power is something that I don't think people can wrap their minds around.

"It's especially bad in the infantry, I think. The concept that I'm going to become a woman and give up all that they hold to be important, but still continue to do that job, that's hard for people to swallow."

For years Jane has studied the macho guys in her unit, "gathering information and cues on how to act". She has learned to pay "super close" attention to detail. "Everything little thing you do is about promoting the fact that you are normal," she says. Ironically, she swears it is this attention to detail that has made her an exemplary airman.

Evan Young, a transgender veteran and the president of Tava, the trans veterans association, says he sees this again and again: "We have so much to lose that we are overachievers. We try to do the best we can so we don't draw attention to ourselves. There are so many of us who receive awards and are the best in our fields, yet so many who have to hide."

Young was investigated by the army after beginning hormone therapy in 2013 but retired before he could be discharged. He would "absolutely" still be serving today if it weren't for the ban, he says, and he knows a lot of veterans who would re-enlist.

Jane now re-enlists every two years, and when she does she has to raise her right hand and swear to defend the US constitution. She loves serving her country, but every time she raises her right hand she wonders how many more times she can swear to defend the rights of others to live as they please, when she can't.

"There's that little clause that says we love everything about you but just don't be that one thing. Well, I am that one thing."

The last time Jane was due to re-enlist she was ready to quit. But then came talk that the ban might be lifted and she felt compelled to stay in, both for herself and to help others. There may be an informal no-fly list but there are also powerful, informal support networks. Trish King runs a weekly group which sees transgender people converge on her home or dial in from all parts of the country by Skype. Young works with veterans who are being denied access to hormone treatment through their healthcare package. Many active service members reach out to others for support, says Jane.

"Sometimes you really struggle to deal with things and you can be dragged down," she says. "Depression can become an issue, but we've built our own networks to help each other."

On an eight-mile circuit near her home, Jane meticulously plans the coming day as she runs. But she also turns over other plans, contingency plans for situations that are harder to predict: plans for what to say if she is asked certain questions; plans for what to do if certain people in her unit find out; plans for how to finally tell her mother.

As her neighbours are slowly waking up, she rehearses lists of her friends and family, dividing them into those she thinks will welcome her and those who will reject her. She has already begun to distance herself from some. "People speak plainly when they don't think they are offending anyone," she says. "That's when you see where their hearts really are."

The anchor in Jane's life, someone whose heart has been in the right place for 20 years, is her wife, Anne. When she eventually comes out to the Air Force, she will draw on the nerve-wracking experience of telling Anne, before she proposed, that she was really a woman inside. Together they have planned for the moment when so much will change.

The career that Jane loves has forced her to put part of her life on hold. She is desperate now to fully become the person who first flickered to life 35 years ago in front of a TV screen in a small town.

She has a plan worked out in her head. It involves waiting patiently for the regulations to change, leaving her unit for another, and making a fresh start with Anne somewhere new. It involves using the leave she has piled up to take time off for surgery, so she can finally have the body she wants. It involves having her chosen name printed on her retirement papers, when the time comes. Above all, she says, it involves doing everything in a way that puts the needs of her unit before her own.

"It's not going to be like turning a light switch off and on and instantly a person changes from one thing to another, it's going to be tough," she says.

"But all I want is to serve my country as me, and for people to recognise me for who I am."

Illustrations by Rebecca Hendin

Follow Joel Gunter on Twitter: @joelmgunter, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

.