The Americans who 'adopt' other people's embryos

- Published

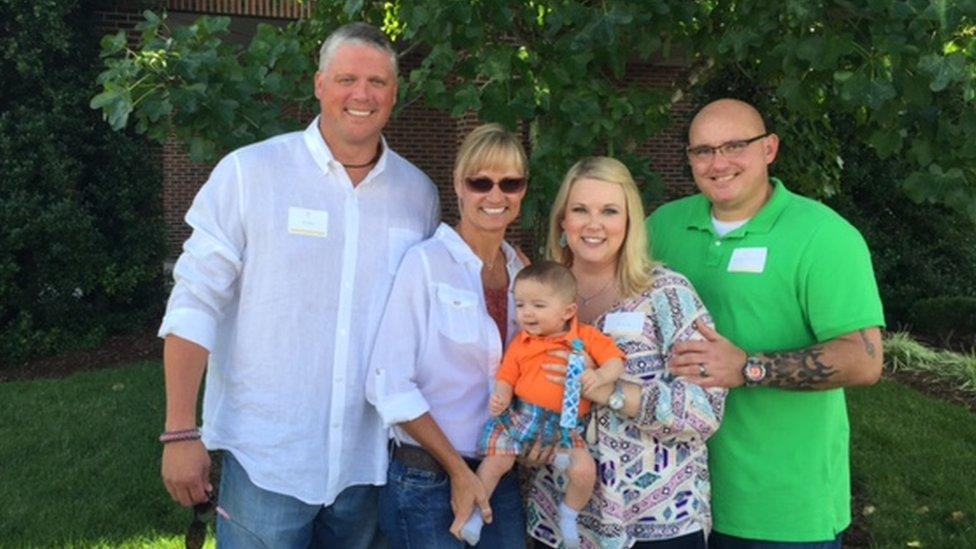

Sawyer Lacey was born as a result of embryo donation a year ago

Couples who struggle to conceive a child are sometimes given the option of using a donated embryo. In the US this is commonly referred to as "embryo adoption", particularly at Christian clinics, where it is regarded as saving a life - and where the future parents may have to be married and heterosexual to be eligible for treatment.

When Jennifer and Aaron Wilson found they could not get pregnant, they knew exactly what they wanted to do.

The couple from North Carolina had the choice of starting in vitro fertilisation (IVF), in which mature eggs are fertilised with sperm in a laboratory. Or they could have tried to adopt a child already in need of a home.

Instead they applied to a specialist Christian fertility clinic in Knoxville, Tennessee - the National Embryo Donation Center (NEDC) - which promised to help them "adopt" an embryo.

Doctors often create extra embryos when a couple undergoes IVF, in case multiple rounds of treatment are needed. But this can leave many left over. More than 600,000 are currently being held in frozen storage in the US, most of them waiting to be used by the couple that created them the next time they want to try to have a child.

But not all of these embryos are needed, and it is estimated that one in 10 are available for embryo donation.

For many couples who have had IVF treatment, what happens to those no-longer-needed frozen embryos is a question that requires careful consideration - should the embryos be kept indefinitely in cryo-preservation or discarded? If the couple believes human life starts at conception, this can be an urgent moral dilemma.

A similar dilemma confronts pro-life couples seeking fertility treatment. Should they opt for IVF, and add to the ranks of frozen embryos preserved in liquid nitrogen? Or should they instead "adopt" a frozen embryo from a donor?

Jennifer and Aaron Wilson say they feel 'called to adopt' embryos

"We're Christian and we're very pro-life so we thought, 'Oh my goodness, this is a great way of putting our pro-life beliefs into action by giving these frozen babies a chance to be born,'" says Jennifer Wilson.

From the couple's point of view the embryos represent tiny lives, frozen in time, that need saving.

"We believe the Bible has several passages that speak to the fact that life begins at fertilisation," says Aaron.

"For us, you take something like IVF, which typically produces a lot of embryos - we view that as a lot of children. Our concern, as Christians, is how do we respond to that, how do we care for this life?"

In November 2010, Jennifer Wilson got pregnant at the NEDC's small clinic in an out-of-town retail park with twins from donated embryos. Abel and Belle have just turned five.

The Wilsons recently returned to the centre in the hope of adding to their family.

Sitting in a hospital bed at the NEDC, Jennifer was handed a photo of three donated embryos that had been carefully thawed - ready to be transferred into her womb.

"The procedure is not comfortable but it's quick," says Jennifer.

Aaron had to wait outside as his wife was wheeled into the operation room. Lying back, with her legs in stirrups, Jennifer watched ultrasound images on a screen as Dr Jeffrey Keenan, president of the NEDC, used a catheter to insert the three clusters of cells into her womb.

It was over in a matter of minutes. All Jennifer and Aaron could do next was wait to find out whether any of the embryos would become a foetus and then, with luck, a baby.

They knew very little about that potential baby apart from its race. The embryos transferred did not come from the same genetic parents as Abel and Belle, and the Wilsons had chosen not to have any contact with them. The only thing they knew about them was the state they lived in.

Other families have different arrangements, however. After undergoing IVF, Andy and Shannon Weber from Alabama had two children, now aged eight and five, and wanted to donate their leftover embryos.

"Our belief is that life begins at conception and the little embryos, they are human life, not just a couple of cells put together. We definitely couldn't destroy them or let them sit there in cryo-preservation forever," says Andy.

But he and his wife were also keen that they should go to a "good, solid Christian" family.

"We wanted a married couple - a man and a woman. We didn't really want a single parent or any sort of alternative lifestyle," says Andy.

"By no means did we care about race or ethnicity. We just wanted the embryos to go to a good home."

The Webers and the Laceys, pictured with Sawyer, still keep in touch

Unlike in the UK where equality laws mean clinics have to treat all patients equally, centres in the US can help donors select parents for their embryos based on criteria such as race, sexuality and religion.

The Webers had Skype conversations with their potential recipient family before deciding that they were suitable. Their chosen couple, Amber and Jerry Lacey, now have a one-year-old son, named Sawyer, from the embryos the Webers donated and the two families spent last Thanksgiving together.

"We see them as uncle, aunt and cousin," says Andy. He and his wife have not yet told their two children that their baby "cousin" is in fact a genetic sibling. "We're going to wait until they can grasp the whole idea."

NEDC medical director: 'Couples should be heterosexual'

Since 2002, the US government has been giving between $1m and $4m every year to organisations that promote awareness of embryo donation and "adoption" (the government's own website uses this term, external).

The NEDC, which has brought about the birth of nearly 600 babies using donated embryos, has been one of the main recipients of these funds. Another is the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption programme, run by the Nightlight Christian Adoption Agency, which has led to the birth of more than 400 children, and helped introduce the term "snowflake baby" into the lexicon, as a way of referring to someone born in this way.

While using donated embryos remains far less common than using donated sperm or eggs, the popularity of this treatment has doubled over the last 10 years, much of it driven by conservative Christian and pro-life groups.

Asked to explain why the NEDC bars same-sex couples and single women from receiving donated embryos, Dr Jeffery Keenan says: "So many people think, 'It's my right to have a child,'... I don't see that. Just because we can do something medically, doesn't make it right."

But other fertility experts disagree with the centre's approach.

"I do not think that here in the US we should be allowing these organisations to make these decisions about who can become a parent and who can't," says Barbara Collura, head of Resolve, the National Infertility Association.

Embryo donation

Success rates vary but about 36% of donated embryo transfers - typically involving multiple embryos - result in live births in the US

Embryos can survive in frozen in liquid nitrogen for an indefinite period of time - babies have been born from frozen embryos for more than 20 years

The average price of an IVF cycle in the US is $12,400, according to the ASRM, while adoption costs between $20,000 and $35,000

Embryo donors are not paid but are reimbursed by the recipient for some expenses

As embryo donation is regarded by US law as the transfer of property and rights, donors and recipients are advised by Resolve, the National Infertility Association, to get legal representation

Meanwhile, Dr Owen Davis, president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), warns that organisations refusing treatment to single women or same-sex couples could be vulnerable to anti-discrimination lawsuits.

"Medical societies certainly feel that one should not discriminate in a medical practice based on sexual orientation, religion or marital status," he says.

He is also concerned about language that portrays the embryo as a human life, rather than a group of cells.

"Terminology is very important," says Davis. "These frozen embryos could not possibly survive outside the body. Their cells have not differentiated, not become a foetus, and certainly not gestated and delivered."

Attributing "personhood" to donated embryos has "dangerous" implications for both abortion rights and other forms of fertility treatment, says Barbara Collura.

"If embryos are viewed are a human being, does that mean destroying or abandoning them after IVF is murder?" she asks.

In fact in both IVF and embryo donation it's likely that a certain number of embryos will die - which is one reason why the Catholic Church is opposed to them.

But while the Webers regard embryos as human lives - and there are reports of others like them holding funerals for discarded embryos - they stop short of describing the destruction of an embryo as murder.

"I don't know," says Andy. "I guess that's a question that only our God can answer."

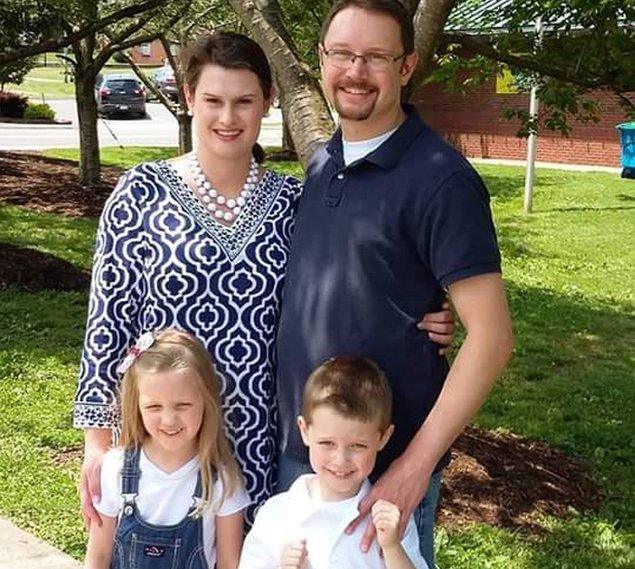

Jennifer and Aaron Wilson had twins Belle and Abel after having embryos transferred in 2010

Jennifer and Aaron know too well that there is no guarantee a donated embryo will become a child in their arms.

Their pregnancy tests after the latest round of treatment came out negative.

They cannot have any more embryos transferred at the NEDC, as they have now had the maximum three cycles of treatment without success, so for now their hope of having babies through embryo donation has run out.

Jennifer says the outcome was a "sad" end to a "hard" six years of attempts to get pregnant. But she says they still feel their "mission" to save the frozen embryos has been accomplished.

"Even if we lose them, we believe those lives are with the Lord in Heaven, and that's better than being left in cryo-preservation," she says.

And despite the loss, Jennifer and Aaron do have what many others who have struggled with infertility dream of. They have two healthy, happy children.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external