Five ways to stop football hooliganism

- Published

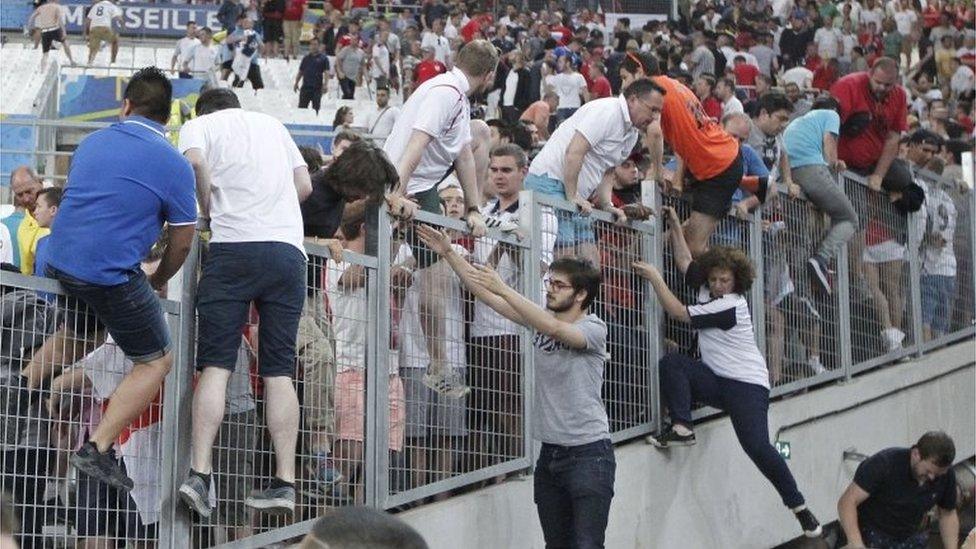

Violence at England's Euro 2016 match with Russia in Marseille - in which more than 30 people were injured - has raised questions over how hooliganism can be prevented. What ideas are there and can they work?

Alcohol ban

The French government is urging all host cities to ban the sale of alcohol in "sensitive areas" near Euro 2016 venues on match days and the eves of match days.

This follows the city of Lens - where England play Wales on Thursday - prohibiting any drinking on its streets in the 24 hours before kick-off.

Alcohol bans have been tried before but haven't always had the desired effect. During the 1990 World Cup there were clashes between police and England fans after sales were halted in Cagliari, the capital of Sardinia.

"This sort of policy can actually provoke a reaction," says Geoff Pearson, senior lecturer in criminal law at Manchester University, who was in Marseille when the latest violence occurred.

"Prohibitions don't work with alcohol. Fans can get angry or find a way around it by getting drink from another source."

He also points out that the Russian supporters who charged at English fans inside Marseille's Stade Velodrome didn't appear to be drunk.

Police used water cannon in Marseille ahead of the England-Russia match

"What I would recommend is that the French police try to do something about bottles of beer being sold," says Pearson.

"They were doing this quite well in Marseille. The bars weren't serving beer in glass bottles but plastic glasses."

Problems began on Friday - the eve of the match - when bars began running out of beer, he says. Fans started buying bottles from supermarkets, and these were used as weapons, he adds.

Mike Layton, co-author of Hunting The Hooligans: The Inside Story of Operation Red Card, thinks alcohol bans might help in some cases but don't get to the root of the problem.

"The hardened criminals don't need beer to stimulate their behaviour," he says, "but others do - those aspiring to become part of the hardcore group and the ones moving around at the back."

Early starts

Strongly related to alcohol bans is the policy of moving matches deemed to have a high risk of violence forward by a few hours - say, from 15:00 to midday on a Saturday.

The idea is to give troublemakers less time to get drunk during the build-up. The Football Association suggests this as a possible plan.

But Layton, who spent more than 40 years policing football violence in the West Midlands, Cyprus and for the British Transport Police, isn't convinced.

"If they are going to fight, they are going to fight," he says. "It doesn't really matter what time of the day it is."

And Pearson says early starts can increase the risk of drunken disorder, with fans coming out of grounds by about 14:00.

"They might then be drinking for another 12 hours, until two in the morning," he says, leading to more late-night violence in city centres.

Empty stadiums

When Manchester City played a Champions League away fixture against CSKA Moscow in 2014, no-one came to watch. Fans were banned, as CSKA were punished for series of offences, including racist chanting.

Clubs in Turkey have faced the same sanction following poor behaviour by fans and players.

Layton thinks locking fans out of stadiums is an "option" for the worst-case scenarios, where violence between rival supporters is expected or has happened recently, but adds that this also punishes the "vast majority" of fans who behave well.

"What are people going to do when it's on TV but they're not allowed into the stadium?" asks Pearson.

"Go to bars. The idea that you want to take people out of what should be a well-manned, secure environment and go to bars that are widely spread out and could turn violent - I've never heard of anything so ludicrous."

Segregation

Fans had to escape a charge by Russian supporters after the Euro 2016 game against England

The Football Association says having clearly separated areas - a common feature at grounds since the 1970s - "has significantly reduced problems of spectator misbehaviour inside stadia".

Clubs often create "sterile areas", involving fabric netting placed over rows of seats, sometimes reinforced by a line of stewards.

But, says Layton, stewards "need to complement overall tactics, not replace the police officers", while barriers must be strong enough to keep fans at high-risk matches apart.

He backs the use of sterile areas, adding: "The problem is that it means not selling all the seats.

"But it reduces the costs for hospitals treating injured people and policing. It also helps prevent any costly damage to football's reputation and image."

At Euro 2016 and Premier League matches there are "football tourists", people who come and watch but have no affiliation, or whose affiliation might change even during the match, says Pearson.

"Policing should be a fluid situation. We should be able to put in a segregation line with short notice."

Fan coaching

The ideas mentioned so far deal with the symptoms rather than the causes of trouble. With this in mind, in the late 1980s Belgium's Standard Liege club decided to educate supporters on appropriate behaviour, setting up a programme known as "fan coaching".

Mimicked in several other countries, it emphasises respecting the opposition and referee and accepting defeat without violence.

Layton calls this technique "diversion", teaching young people who play and watch football to hold better values. It includes talks from star players and reformed hooligans, who can tell young people that violence leads to injuries and criminal records.

Layton thinks the best way to get this message across is to enforce the law. Twenty people have been arrested over the Marseille violence, but he thinks this isn't enough.

"Lots of people have got away with it," he says. "I would have thought, with CCTV cameras, the police would have caught a lot more.

"There needs to be speedy justice in these cases. A lot of football hooligans think that because they're in a group they're anonymous. We have to show them that they're not."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.