Rescuing America's roadside giants

- Published

Anyone making a road trip across America will sooner or later run across a giant statue - a cowboy, an American Indian chief or a lumberjack, perhaps. Many, now half a century old, are falling apart, but one man and his friends are tracking them down and bringing them back to life.

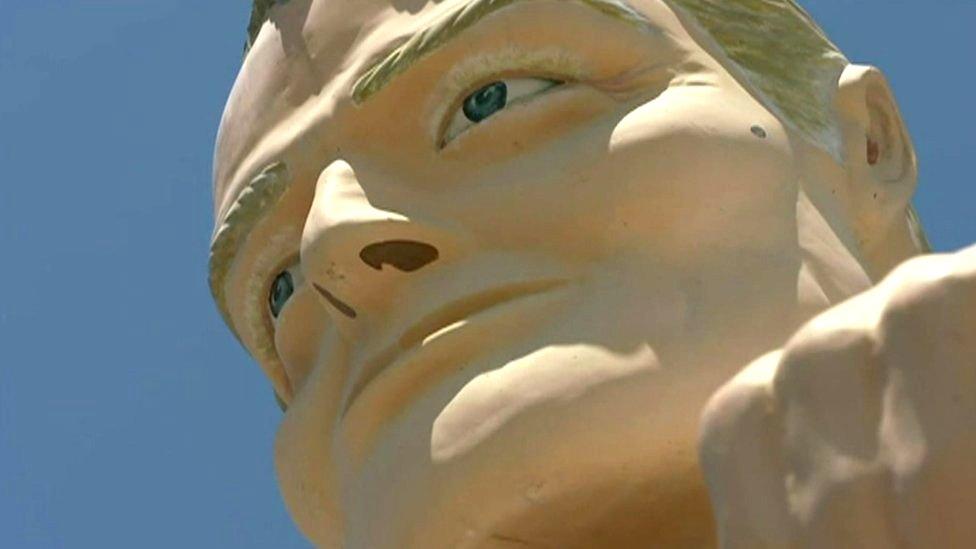

On the concrete floor of an Illinois garage, a giant rests in pieces. His head is the size of a wardrobe, his bulging torso bigger than a double bed.

The 23ft-high (7m) colossus stood for 45 years outside Two Bit Town, a now-abandoned tourist attraction in Lake Ozark, in the heart of the American Midwest. Chief Bagnell, as he was nicknamed, was one of thousands of giant statues designed to entice travellers to pull off US highways.

Now he is getting a makeover thanks to Joel Baker, a television audio technician by day who is America's leading restorer of fibreglass figures made in the 1960s and 70s.

"Over the years these guys have been in the weather and the wind. Some of them have been hit by cars," says Baker as he weaves his way through the outhouse strewn with body parts.

With the help of three friends, he has spent his evenings for past three months stripping off layer after layer of paint from Chief Bagnell's body. They have patched up cracks and painstakingly polished around every feather in the warrior's headdress, and every wrinkle in the face.

What started out as a fun hobby for Baker five years ago, tracking down the statues made by a California-based boat building firm, International Fiberglass, has developed into a mission to save and repair them. , external

The firm began making giant human figures in 1964 after a restaurant in Arizona ordered a model of Paul Bunyan, a giant lumberjack in American folklore. It made hundreds more over the next decade, of which between 180 and 200 still exist, according to Baker.

The man rescuing America's roadside models from ruin

After Paul Bunyan came cowboys, golfers, pirates and goofy-looking country bumpkins, advertising everything from tyres to golf courses.

"These giants were just going out all over America," says Baker.

The first American Indians were purchased by Pontiac dealerships, while the cowboys were made for Phillips 66 petrol stations.

The figures were also a common sight outside car repair workshops often carrying an exhaust pipe - a muffler in American English - and have become known as Muffler Men.

But there were also about 20 female models - so-called Uniroyal Gals, made for the Uniroyal tyre company in 1966, some clad in a bikini, others in a skirt, T-shirt and heels.

By today's standards the gals in bikinis, the stereotyped American Indians and country bumpkins might be considered inappropriate. But they reflect the values of the period - and so it's no surprise that the vast majority of Muffler Men were white and male.

"The American hero was this big brawny guy who's going to change your tyre or chop down your tree," says author Doug Kirby, one of the founders of RoadsideAmerica.com which maps the giants' locations, external.

"It's all quite politically incorrect now, of course."

Nitro the Uniroyal Gal at a garage in Blackwood New Jersey

For Baker and his fellow enthusiasts, the Muffler Men epitomise the road culture and mass production of the 1960s - but the idea of building models of epic proportions to attract passing trade goes back much further in American history.

The founding father was James V Lafferty, who built a six-storey elephant on a strip of undeveloped coastal land just south of Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1881.

Lucy the Elephant was intended to attract property buyers and visitors and still stands as a tourist attraction today, having survived Hurricane Sandy in 2012. In 1882, Lafferty filed a patent on giant buildings "of the form of any other animal than an elephant, as that of a fish, fowl, etc.", which he claimed was his invention.

People can still visit Lucy the Elephant today

One of the first examples of giant novelty architecture at the roadside was a 64ft-high (20m), bright orange wooden bottle on the outskirts of Auburn, Alabama.

Built in 1921 to advertise Nehi soft drinks, and billed as "the world's largest bottle", the structure housed a service station, grocery shop and living space. It burned down in about 1936, but the area on the map is still called The Bottle.

An Alabama newspaper printed this image when The Bottle burned down

Traders had always relied on images rather than words to advertise goods to America's multilingual immigrant population, says Brian Butko, a historian whose books include Roadside Giants and Roadside Attractions.

But as time went on, scale became important.

"It is a lot harder to attract attention when cars are going by at 50 mph," says Butko. "That's where the roadside giants got started. They were trying to draw people off the road from long distances away."

When the modern American road trip really got going after World War Two, with the rapid growth of car ownership and the new interstate highway system, more and more businesses competed to cater for road-weary travellers.

"A lot of the people I talk to say Muffler Men remind them of their childhood in the 60s," says Joel Baker. "They remember being in the back of their dad's car, they remember the make and model of the car and driving by whatever restaurant the Muffler Man stood at."

But just as Muffler Men multiplied thanks to the success of the car industry, they suffered when it stumbled in the 1970s. International Fiberglass ceased operations in 1972, and slowly attitudes towards its giants began to change.

"There was a sense of embarrassment about these models," says Butko, when the fuel crisis and subsequent recession caused some dealerships, fuel stations, and repair workshops to close. More efficient cars had less need to stop in small towns, and just drove past.

An American Indian Muffler Man outside a truck stop in Kentucky

Many of the Muffler Men were "just trashed", says Joel Baker.

Among those that were simply neglected, he has discovered many in dire condition, with arms and heads falling off. It's the contrast between childhood memories of the models and their current state that has driven him to take action.

And it seems communities are beginning to appreciate the figures again as other authentic elements of the roadside, such as diners and petrol stations, disappear.

"In lots of places, they went from tacky things that half the town hated, to becoming a cherished landmark," says Kirby.

Businesses are also harnessing their pulling power once more.

Shawn Fennel says his Muffler Man is good for business

Shawn Fennel, who owns a repairs garage for vintage cars near Nashville, Tennessee, paid $20,000 (£14,000) for a Muffler Man to stand on his forecourt last year, and transported it across the country from El Monte, California.

"It's every day that somebody stops and has their picture made," Fennel says.

Doug Kirby says travellers are also taking greater interest, and sometimes going out of their way to see one.

"There's awareness that a roadside attraction or model is something of a rarity," he says. "It's a fun diversion, something that's pretty simple - just as it always was."

So Muffler Men made in the 1960s are still doing their job.

In the garage, Joel Baker and his team are slowly revitalising the giant war chief, with a view to reinstalling him in Lake Ozark this summer.

Two colleagues spray the model with grey primer to prepare for repainting. Baker stands back and smiles with satisfaction.

"There's a pull to these giants," he says. "That's why they were made - to attract attention. And it worked."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external