Africa's modernist enigma

- Published

Last year, more people fled to Europe from Eritrea than any other African nation. The government in Asmara has recently been accused of crimes against humanity, but when Mary Harper was given rare access to the country she was surprised by what she found.

I push back the thick, deep red velvet curtains and find myself in complete darkness. Drops of rain come through the ceiling, and hit the floor - hard.

Someone turns on a switch. A dim, flickering bulb does its best to light up the place - I am inside a huge cinema.

Slowly, I make out elegant shapes on the walls - leaping antelopes, pineapples and dancing maidens. On the floor, in front of the screen, stand white pillars topped with the heads of lions.

I hear a tap, tap, tap behind me. A very old man in red trousers, a white shirt and black jacket approaches: "I have worked here in Cinema Impero for more than 40 years," he says. "We have seats for 1,800 people."

He takes me out to the foyer, which seems to be a sort of hangout for the disabled people of Asmara. A man in a wheelchair, a blind child and a woman bent over on two wooden sticks cluster around a giant black projector.

Others order drinks from the bar, its polished wooden shelves neatly stacked with glasses, their stems brightly coloured. Film posters on the wall advertise La Dolce Vita and An African Affair.

Disabled people socialise in the foyer of the Cinema Imperio

It is as though some kind of magic powder has been sprinkled on Asmara, freezing in time its clean-lined 1930s architecture. Eritrea used to be an Italian colony and its capital, known as Africa's La Piccola Roma or Little Rome, has been described as one of the world's finest collections of modernist buildings.

This year, Eritrea submitted a request to Unesco for Asmara to be declared a World Heritage Site.

I'm told the young country's first and only president, Isaias Afwerki, has ordered central Asmara to stay as it is, as a kind of museum to modernism. This makes it starkly different from most other African capitals, where a thoughtless rush of construction in recent years has resulted in a chaotic mishmash of skyscrapers, apartment blocks and building sites.

There is not much building going on in the centre of Asmara but construction is under way on the outskirts of the city - it doesn't interfere with the skyline or the wide elegant boulevards lined with date palms, though.

The modernist buildings are fading and crumbling at the edges. Most are still being used, although not the Fiat Tagliero garage, designed by the Italian architect Giuseppe Pettazzi in the 1930s.

It looks like a futuristic plane, its concrete cantilevered wings stretching out with no supports.

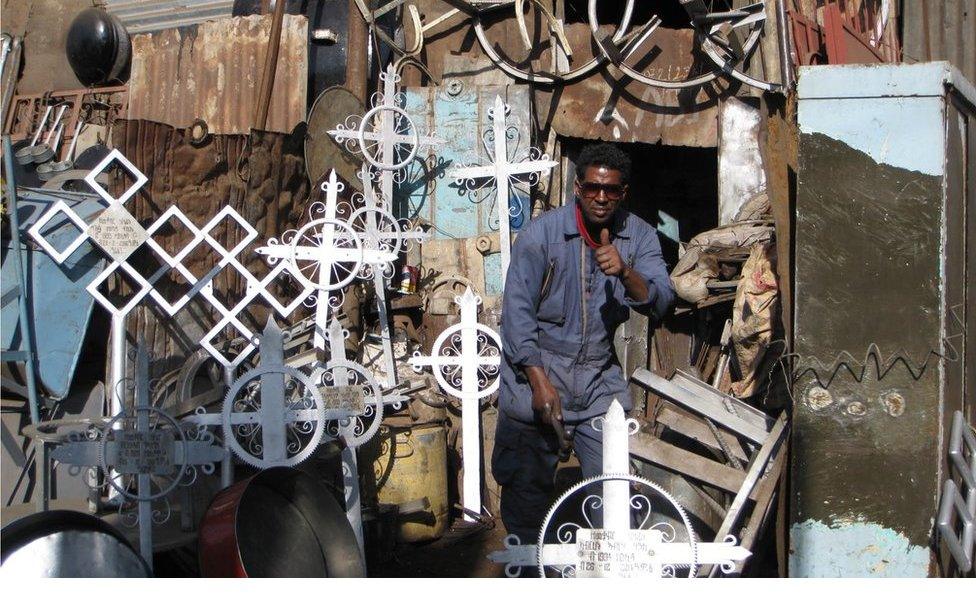

Mary Harper's Eritrea in pictures

Fiat 600s from the 1950s and 1960s buzz past along with a lilac VW Beetle, a horse and cart, Toyota Land Cruisers and yellow taxis. Two men in wheelchairs propel themselves along at great speed - with the help of ski poles.

Cyclists whizz past in bright shiny lycra - cycling is another legacy from the Italian colonial period, and Eritreans are starting to make quite a splash on the international circuit. Last year, the Eritrean cyclist, Daniel Teklehaimanot, became the first African to wear the King of the Mountains jersey in the Tour de France.

Old men sit in pavement cafes, sipping espressos. The wide awnings and design of the buildings make it look more like Rome or Paris than an African city.

They swap war stories - tales from the trenches when they fought and won a 30-year conflict with Ethiopia. Images of young, wild-haired independence fighters are painted on the walls of many buildings, including a traditional bowling alley, which doubles up as a pool hall.

But behind all this charm lurks something else. As in the darkness of Cinema Impero, details only start to emerge once you spend time looking, listening and waiting.

Cars from the 1950s and 60s, like this Fiat, are a common sight in Asmara

There are hardly any police visible on the streets. But people tell me there are informants everywhere.

I meet Eritreans who have been in obligatory national service for more than a decade.

Between 10% and 20% of conscripts are in the military, according to the government. The rest, it says, have civilian roles in areas such as teaching, healthcare, state-owned companies and government departments.

"I have been serving for 15 years," says one man in a market. "I supplement the low pay by selling spices in my spare time." Some say they feel trapped in national service and want to leave the country. Others want to push for change from within.

But then again, I meet people who have returned from a comfortable life abroad to live and work in Eritrea. One young woman who grew up in Sweden asks, "Why does the outside world hate Eritrea? Why are we called the North Korea of Africa? What can I do to change that?" She says she has no regrets about leaving her well-paid job in Stockholm. "Eritrea is peaceful, it is safe and there is no violent Islamist extremism. Of course there are challenges, but this is home."

It is very difficult to work out what's going on.

Human rights groups say there are thousands of political prisoners, tortured and kept in underground cells and shipping containers.

A United Nations Commission of Inquiry says crimes against humanity, including murder, rape and enslavement, have been committed ever since Eritrea became independent 25 years ago - and it has called on the UN Security Council to refer Eritrea to the International Criminal Court.

The government officially denies these charges, although ministers tell me there are 30 or 40 political prisoners. They say most of them are politicians, military men and journalists who "committed acts of treason" after the 1998-2000 border war with Ethiopia. Some are known as the "G15", a group of senior officials who wrote an open letter to President Afwerki in 2001, criticising him for postponing elections and failing to implement the constitution.

The government says torture is banned and denies prisoners are kept underground. One official said if anyone was caught torturing a prisoner, he or she would be severely punished.

I read reports that say Eritreans are afraid to think, let alone speak. Yet almost everyone I meet is happy to talk, even with an aggressive TV camera and big fluffy microphone pushed in their faces. And I am not accompanied by a minder.

Eritrea has been accused of political repression and torture, allegations which it denies

This is very different from some other authoritarian African countries I have worked in. In Sudan, I had a government official by my side all the time, and was locked up for a day after I asked soldiers which country their weapons came from. In other countries, plain-clothes security agents have raced up to me on motorbikes as soon as I started interviewing people in public, carting me off to the police station regardless of the fact I have a permit to work as a journalist. In Eritrea, I am asked to show my permit from time to time, but am never prevented from working.

I meet Germans from the Leipzig Philharmonic Orchestra who have come to perform as part of Eritrea's 25th anniversary of independence. They tell me they were warned not to come here because the country is dangerous, a sort of giant slave camp. Yet they delight in how safe they feel, how clean Asmara is, how friendly its people are.

The musicians play in Cinema Asmara, which was originally built as an opera house in the 1920s. The crowd claps and cheers as they perform Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, waltzes and polkas by Johann Strauss, and Eritrea's national anthem.

I start to feel I am going to have to empty my mind and start all over again if I am even going to begin to understand this country.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.