Entebbe: A mother's week of 'indescribable fear'

- Published

Forty years ago, the hijacking of an Air France plane from Israel began a week of high drama, ending with the surprise rescue by Israeli commandos of over 100 passengers held at Entebbe.

Here, one of the freed hostages tells how her life hung in the balance for seven tense days.

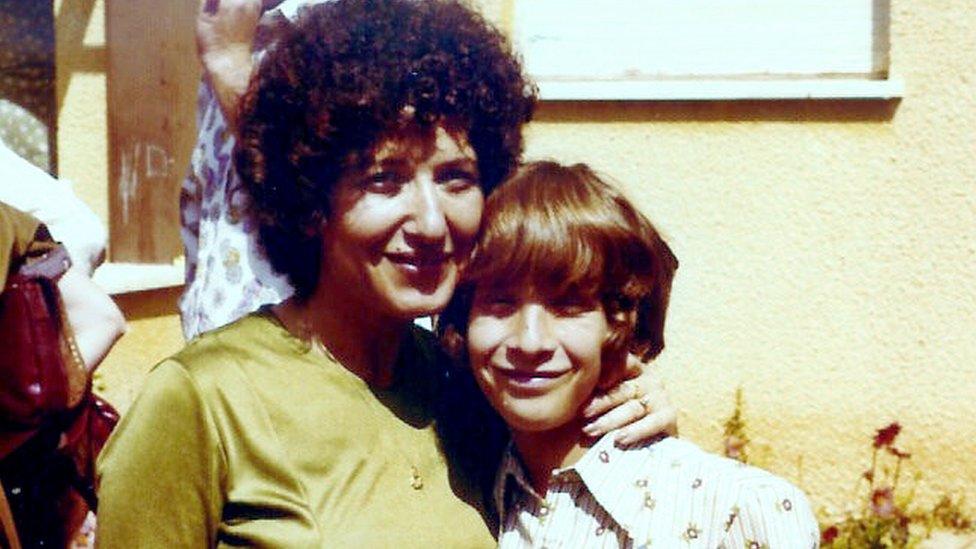

It was only by a twist of fate that Sara Guter Davidson and her family were on board Air France flight 139 when hijackers struck on 27 June 1976.

"Even now, I can still feel the fear I had for my children," says Sara, now 81. "I feel like it was yesterday - I can feel the fear the same as I felt it for a whole week 40 years ago."

Seated towards the rear of the plane with her husband Uzi and sons Benny, 13 and Ron, 16, the first Sara realised something was wrong was when she saw a stewardess rushing down the cabin.

"I heard a shout and I saw her coming - her face was white and she was very frightened. I told Uzi, 'Listen, I think we've been hijacked.'"

The flight had originated in Tel Aviv and the hijackers had boarded during a stop-off in Greece.

Former Mossad agent has collected items from the Entebbe raid for an exhibition

"Our travel agent never mentioned we'd be stopping in Athens," Sara recalls. "If we'd have known, I'd never have taken the flight because I did not trust the security there."

Benny had recently been barmitzvahed (Jewish coming of age ceremony) and the Davidsons had planned to celebrate with a party, but when Sara's father suddenly died they decided to take the children abroad instead.

A family holiday would do them good, they felt, and help Sara deal with not only her bereavement but her recovery at the time from surgery for cancer.

Armed with guns and grenades, the hijackers - two Germans and two Palestinians -took control of the plane and 250 terrified passengers and 12 crew.

"It is a totally strange kind of fear," says Sara. "It's a fear that you're going to die in the air, you don't know how. You have your children beside you. It's a very terrible and heavy fear. It's impossible to describe how terrible the feeling is," she says.

Sara Guter Davidson

'Great shock'

The hijackers announced their demands - the release of 53 militants jailed in Israel, France, Germany, Switzerland and Kenya, and a $5m ransom.

"That really worried us," said Sara. "We knew that meant negotiations involving five countries, which would be a slow and difficult process."

Find out more

Watch Sara Guter Davidson's story on BBC World Service Witness programme

Listen to Witness via the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast

As the plane changed course, the hijackers began collecting passengers' passports and other documentation.

Uzi, an Israeli air force navigator, fearing what would happen if they found out, chewed up his air-base permit and hid it in a drinks can.

Eventually the aircraft descended into Benghazi, Libya, where it refuelled. The plane took off again, flying for a further five hours before landing in Entebbe, Uganda.

Before leaving Israel, Sara's mother had given her a notebook to keep as a diary of their trip.

Instead, she used it to document the hijacking, recording events in real-time.

"The flight to Uganda was a nightmare," she wrote. "We had no idea where we were going. People had terror written all over their faces. Time moved very slowly."

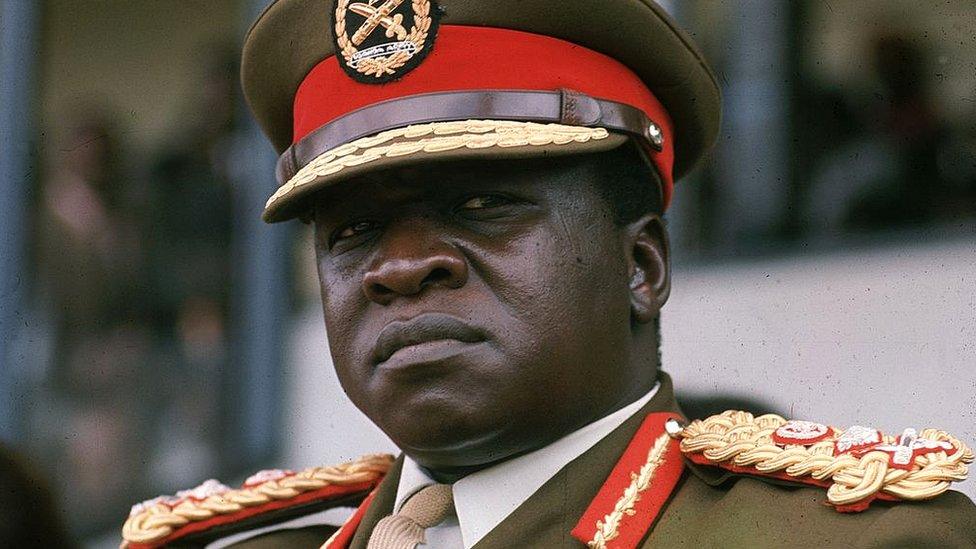

As the plane sat on the tarmac, the passengers saw out of the window the figure of Idi Amin, the president of Uganda and an erstwhile ally of Israel. It gave them cause for optimism.

"Seeing Idi Amin, because we thought he was a friend of Israel, we were sure that we were going back on our way," Sara says.

But the notoriously erratic Amin was in collusion with the hijackers and at least three accomplices who were already in place at the airport.

After nearly 24 hours on the plane, the passengers and crew were shepherded into an old terminal building, where Amin, accompanied by a phalanx of journalists, spoke to them.

Idi Amin

President of Uganda 1971-1979; achieved power in a military coup, and is believed to have been responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths

Among many human rights abuses, Amin expelled 80,000 Asians from Uganda and expropriated their properties

Fled the country following defeat by rebel forces; lived in Saudi Arabia until his death in 2003

"He told us that although he supported the group [Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations] that was holding us, he would do whatever he could to help us," Sara says.

"He was pretending to be neutral, but the sight of him standing there with the terrorists - we just didn't believe him."

The passengers - families, friends and strangers - and crew now found themselves held at gunpoint in overcrowded quarters, ringed by Ugandan troops.

"It was a great shock that we are prisoners, and we are surrounded with Idi Amin's soldiers and terrorists," says Sara.

"People were crying, shouting, getting nervous - it was a very unpleasant feeling.

"We thought that we were so far away that we really didn't know how we could be saved - we were sure our government would try to do whatever it could - but we didn't see any solution, and this made us very depressed."

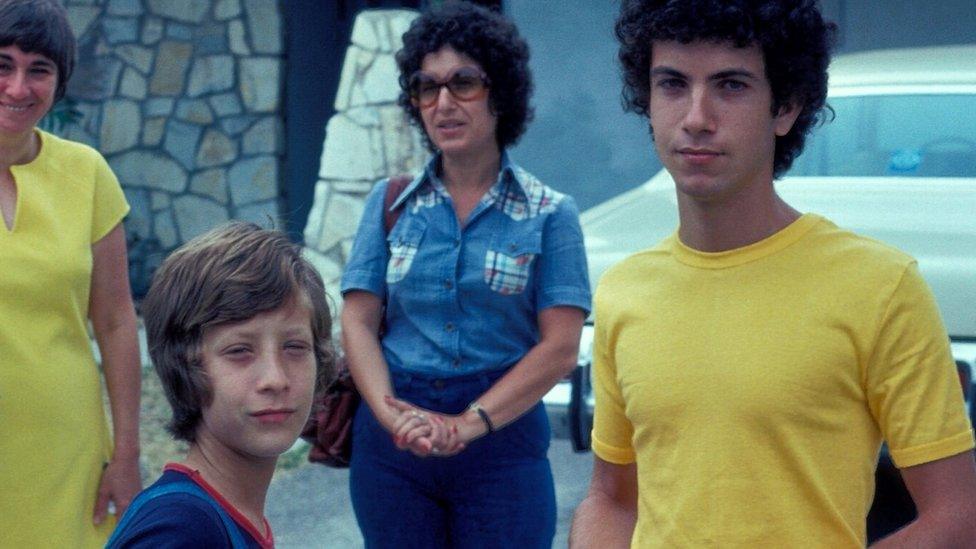

1976: Sara (middle) in New York with her two sons Benny (front left) and Ron (right)

'Dream became a nightmare'

Conditions were rough. Lights were kept on day and night, people slept on the floor or benches, and they were blighted by heat and mosquitoes.

The hostages were given food but the meals never varied - meat, rice, potatoes and lots of bananas. Sara jokingly called it the "Ugandan diet".

As the hours turned into days, the captives found various ways to cope with the stress. Some gave lectures, others played games, and children made new friends.

The hijackers had set a deadline of Thursday for their demands to be met and the strain on the passengers grew.

Sara, for the sake of her sons, tried to keep her emotions in check. The elder, Ron, became withdrawn, while Benny was prone to breaking down and begging to know when their ordeal would be over.

"Sometimes when everything around us seems hopeless," Sara wrote in her notebook, "and people say that we won't get out of here alive, he [Benny] can't take it any more.

"The dream of a fantastic family vacation has turned into a nightmare."

The nightmare was about to take a turn for the worse.

On the third day, the hijackers began calling people's names and ordering them into a second, smaller, squalid room.

It became clear they were separating the Israeli and non-Israeli Jewish passengers from the rest, immediately evoking the horrors of the Nazi selections in World War Two when Jews were picked out to be sent to their deaths.

"For me," says Sara, "because I knew about my grandparents and aunts and uncles - all of them were killed in [the Nazi extermination camp] Treblinka - I had a terrible feeling, but among the passengers were also Holocaust survivors still with numbers [tattooed by the Nazis] on their hands.

"We knew we were going to have a very tough time," she says. "I didn't care about my own life as much as my boys', who had just started theirs. I was so frightened for them."

Operation Entebbe - a timeline

27 June, 1976: Air France flight 139 from Tel Aviv to Paris hijacked; refuels in Libya

28 June: Hijacked aircraft lands in Entebbe, Uganda

29 June: Hostage-takers issue demands, threaten to kill passengers from 14:00 on 1 July

30 June: 47 passengers released, questioned by Mossad in Paris

1 July: Israel offers to negotiate; hostage-takers extend deadline, release 101 passengers

2 July: Israeli special forces rehearse rescue

3 July: Israeli cabinet approves rescue, assault force dispatched to Entebbe, storms airport

4 July: Freed hostages arrive back in Israel

'Waiting and hoping'

At the same time, the hijackers released a first batch of passengers (the French captain and his crew rejected an offer to leave, refusing to abandon any hostages). The following day, dozens more were freed.

Conditions for those left in the separated group deteriorated. Food was scraps, and the area was infested with flies.

Benny mixed with the children, but exhaustion took its toll on Ron, who fell ill.

A few days later, the group was allowed to return to the departure lounge with other hostages.

On Thursday night, the fifth day of the crisis, Amin made another appearance, but this time his tone was different, says Sara.

He told the hostages that although Israel had not yet complied with the hijacker's demands, he had persuaded them to extend their deadline until Sunday.

Hearing the word "deadline" terrified Benny.

Sara tried to reassure him it did not mean they would be killed, but her words had no effect, she said.

Benny was crying, Ron had a fever, and morale had ebbed away.

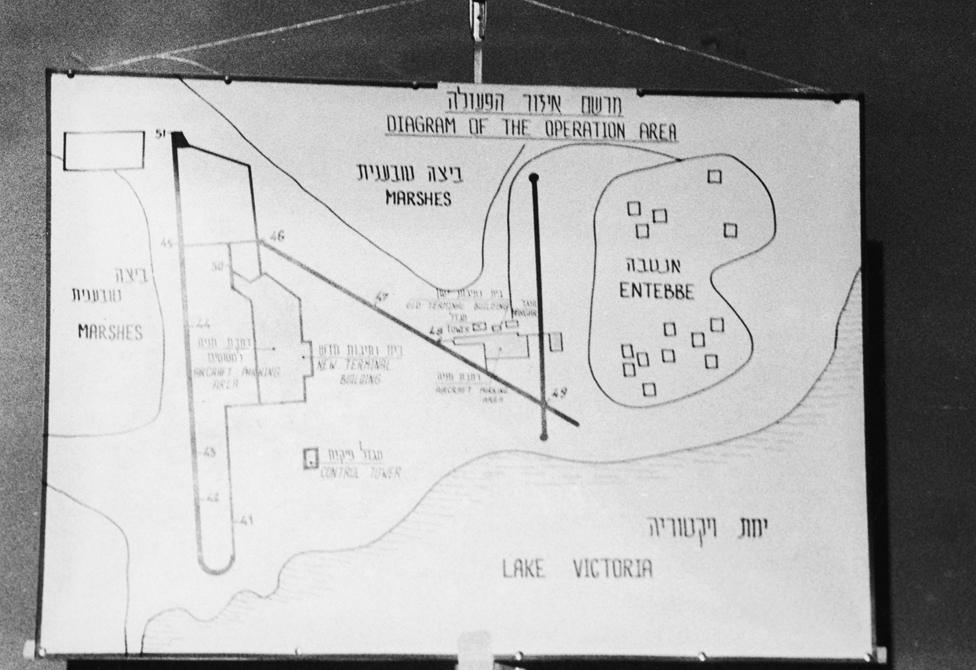

An Israeli army map of Entebbe airport

The passengers speculated what their government would do - although "it was clear to us that Israel's policy of not releasing terrorists was at work," says Sara.

"There was no answer," she says, "only to keep waiting and hoping."

By Friday, Ron's temperature had dropped but tensions were high.

"If we were going to be killed," says Sara, "I knew I wanted to die before my husband and children. There was just no way I could watch it happen to them."

As the deadline loomed, with no sign of progress, passengers turned to Uzi and asked him, based on his experience in the air force, what the chances of being rescued were.

"He calculated the distance between Israel and Uganda and told them 'no way'," says Sara.

Amin reappeared the following day for what would be the final time, telling the passengers he could foresee an end to the crisis.

He did not give any specifics, and as dusk descended, the hostages prepared for a seventh night, their predicament seemingly increasingly hopeless.

'Like an angel'

It was nearly midnight. The hijackers were sitting on benches outside, relaxing and chatting. The Davidsons found a spot on the floor and settled down to go to sleep.

"Suddenly we heard shooting," says Sara. "Amin had said Sunday was the deadline, and negotiations weren't getting anywhere, and we were sure they were starting to kill us. We thought 'this is it'.

"I grabbed Benny - I didn't see Uzi and Ron because it became terrible with shooting all around - the noise and smell and people shouting, and I just covered Benny's body with mine.

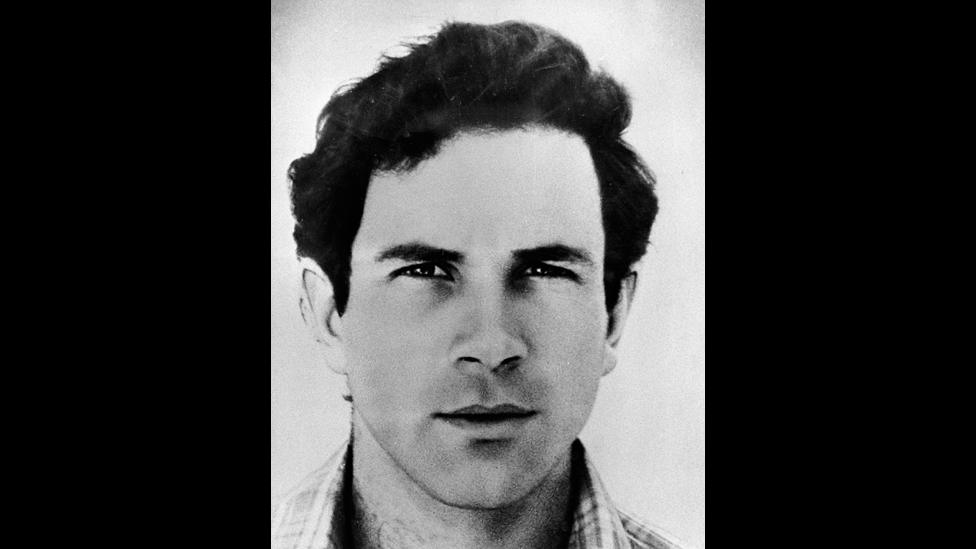

Yonatan Netanyahu (the brother of the current Israeli prime minister) led the rescue operation but died in action

"The noise was loud but after a few moments somebody said: 'There are Israeli soldiers here.'

"I lifted my head and I saw a soldier dressed like a member of the Ugandan army with a white hat - and he said in Hebrew: 'Listen, guys, we've come to take you home.'

"I didn't believe what I was seeing, even now I can't describe it - seeing the soldier, it was as if an angel had come down from the sky."

In one of the most daring operations in its history, Israel had secretly despatched a unit of elite commandos - led by Yonatan Netanyahu, the brother of current Prime Minister Benjamin - to rescue the hostages.

They had flown eight-and-a-half-hours over 4,000km (2,500 miles), through hostile territory and beneath the scope of enemy radar, to mount a surprise raid.

In under one hour they had killed all the hostage-takers, led 105 bewildered and shocked passengers and crew out of the terminal and into a waiting Hercules transporter plane. They were on their way home.

Three hostages lost their lives in the operation, as well as Yonatan Netanyahu, the only fatality among the troops.

"When we landed at the airport near Tel Aviv, it was unbelievable. People were singing and dancing - it was as if all of Israel was there to greet us," says Sara.

The return of the hostages

Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who had authorised the mission, was among those there to welcome them home.

He had got to know Uzi's father, who had been part of a committee of the hostages' relatives who had held meetings with Rabin during the crisis.

The prime minister called Sara and her family over.

Yitzhak Rabin (left) and Shimon Peres welcome hostages back to Israel

"We were in such a state of shock," she says. "I remember I wanted to say thank you but the words just wouldn't come out. I just held Benny in my arms."

In the years that followed, Rabin became a personal friend of the Davidsons, even attending both Ron and Benny's weddings.

It was just two years ago that Sara met her rescuer for the first time since the raid - until then his identity had not been revealed because of the secrecy of the unit he served in.

"We met at a reunion of the commandos and hostages, it was very emotional - I owe him my life," she says.

2014: Sara reunited with one of her rescuers

Forty years on, Sara says the events of the summer of 1976 are still relevant to today's world.

"After Entebbe I really expected the whole world to take action to stop terrorism, to stop people from being able to do things like this - but sadly it's still going on."