Prosopagnosia: How face blindness means I can't recognise my mum

- Published

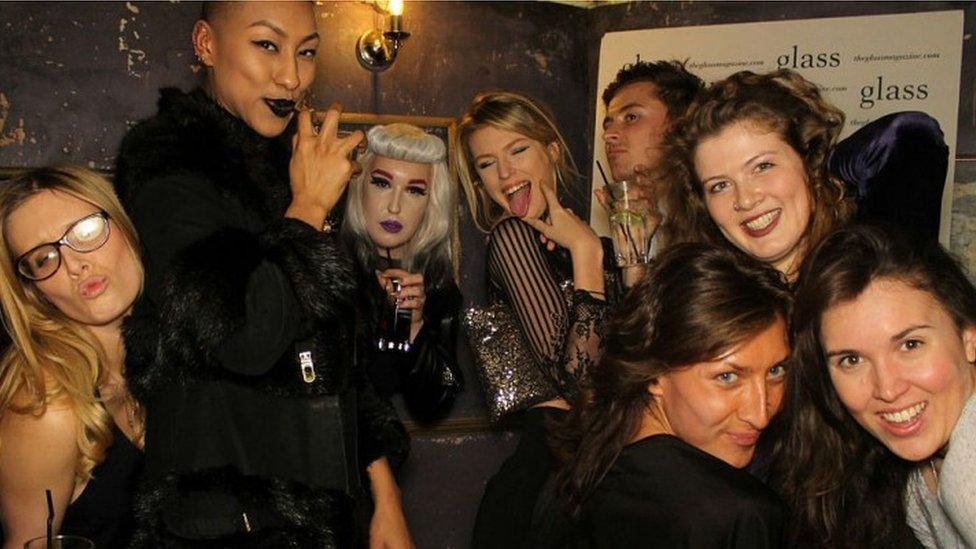

Evie Prichard (l) has sometimes failed to recognise herself or her mother Mary Ann Sieghart (r)

When you see someone you know, the easiest way to identify them is by their face - but not everyone can do this. It's thought that one in 50 people may have prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Twenty-four-year-old Evie Prichard, who has the condition, explains what life is like when you struggle to recognise your friends and family.

I was 19 when I bumped into a nondescript guy at a party and asked him if he knew an ex-boyfriend who I'd broken up with a couple of months earlier.

The familiar loud shirt and stench of CK One should have been enough to warn me who I was talking to, but instead for some reason they made me think that this stranger was a friend of my ex, who had perhaps borrowed his shirt and cologne. Unfortunately, on this as on many occasions, the sleuthing which accompanies most of my social interactions had let me down - inevitably, that guy was my ex.

All he'd done was cut his hair and shave his stubble, but because I was in high heels our height differential was also off. My face blindness means that I rely on cues such as hairstyle and height to tell people apart, and without these I am completely adrift.

In a sense this was a triumph. It certainly deflated his ego a little. But it was also one of many instances in which my face blindness has conspired to make me look like an idiot.

To me, a face is like a dream. It's incredibly vivid in the moment, but it drifts apart seconds after I look away until all that's left are the disjointed features and a vague memory of how it made me feel.

Living with a brain that lacks this one crucial function can be extremely debilitating, but most of the time it is merely inconvenient and gut-wrenchingly embarrassing.

What is prosopagnosia?

Prosopagnosia is a neurological condition where the part of the brain that recognises faces fails to develop

It can stop people recognising partners, family members, friends or even their own reflection

It was once thought to be caused by brain injury (acquired prosopagnosia) but now a genetic link has been identified (developmental prosopagnosia)

Acquired prosopagnosia is very rare but as many as one in 50 people may have developmental prosopagnosia

There's no specific treatment, but training programmes are being developed to help improve facial recognition

There was even a time I caught my own reflection in a mirror across a bar and genuinely didn't recognise it. I'd thought several slightly bitchy thoughts about my own sweaty face before I realised exactly who it was I was mentally eviscerating.

Another time, my curly-headed mother had her hair straightened, and I walked straight past her in the street.

Studies have shown that up to 2% of the population could be living with prosopagnosia, commonly known as face blindness. Many don't even realise they have it.

The severity of the disorder ranges from the relatively manageable to the "Oh gosh, sorry, I thought it was my husband I was kissing". Most diagnosed sufferers fall somewhere between these poles.

My prosopagnosia is severe but I can recognise close friends under normal circumstances, and have about a 50-50 chance of managing it after a haircut or a change of glasses.

Although Evie's mother and grandmother also had the condition, her sister Rosa (l) does not

For many, the situation is much worse. I've heard stories of people being robbed by strangers claiming to be their family, or of children wandering off with strange men.

Luckily nothing like that happened to me when I was a child - I've known about my condition all my life, so I've always been careful.

I did find it almost impossible to recognise my classmates, though, which made making and retaining friends a struggle. I still remember wandering the corridors crying on my first day of secondary school: I'd gone to the loo and didn't know which class to rejoin because I couldn't recognise either the teacher or the pupils.

People are often baffled when I tell them about my prosopagnosia. In fact I've had every possible reaction, from disbelief to fascination to hysterical laughter. One man even accused me - behind my back - of making it up to flirt with him.

Until recently, it was thought that prosopagnosia was a very rare condition which mainly resulted from brain damage, but it is also more commonly a genetic condition. In fact it runs in my family - it has afflicted my mother, my grandmother and my great-grandfather, although my sister Rosa seems to have evaded the curse.

Evie (second right) at a party with friends, only one of whom she can recognise

It was only in this century that researchers began to realise exactly how many people in the world were quietly living with the condition. These were people who, like me, had had prosopagnosia all their lives, and as a result had become very adept at hiding their deficiencies.

Like a blind person who can recognise family by their footsteps, prosopagnosics are forced to develop unconventional ways of discovering who it is we're talking to as we fumble our way through our social lives. From the obvious markers like hair and voice, to posture, gait and eyebrows, we rely on dozens of tactics to get through ordinary life.

And if all else fails, we are excellent bluffers. When I meet someone I might know, I can generally project just the right level of friendliness to be acceptable to childhood friends or complete strangers. It's a very hard line to tread - never play poker against a prosopagnosic.

That said, I'm still prone to making an absolute idiot of myself. Once I was being filmed for a documentary, and two girls I'd known well in secondary school were paraded past my table in an almost empty pub for about 20 minutes without my having any idea I'd met them before.

One of them sold me my beer, and even though I looked her in the eye and smiled as I took the change I still somehow failed to catch on.

Mary Ann Sieghart on living with face blindness.

Last weekend, at Glastonbury, I was camping with friends and a whole collection of their friends, most of whom I'd never met before. Throughout the festival people came up to join us as we danced and I had no idea if these were the same people who'd spent the previous days drinking and chatting with me.

It was even worse when my sister and I snuck into the VIP area one afternoon - apparently there were all sorts of celebrities around, but I didn't have a clue.

Although I can, and often do, play the condition for laughs, there's something exhausting about scrambling for someone's identity at every social encounter. At university in a relatively small town, I was pretending to recognise tens of people every day, and brutally offending acquaintances nearly as often.

I'm a naturally sociable person. But after a couple of my closest friends admitted that the first few times they'd met me they'd thought I was stuck up and cold because I kept ignoring them, it became harder and harder to want to meet new people.

Find out more

Evie Prichard and her mother Mary Ann Sieghart are featured in Who are you again? on BBC Radio 4 on Friday 1 July at 11:00

Or you can listen later via the BBC iPlayer

In the end it was student journalism that saved me. Getting the word out about prosopagnosia through a regular column allowed me to become "that face blind girl". While perhaps not everyone's chosen niche, this was the most efficient way I had ever found to explain to the people I'd inadvertently hurt exactly why I was treating them like strangers.

Ironically, as I became a recognised face on campus, it became more and more acceptable for me to fail to recognise others.

Faces are an important part of identity. Not to be recognised feels terrible - it's as if you've been overlooked, like someone's saying you don't matter.

But it's nothing to the pain of knowing that you're hurting people's feelings constantly, making them feel undermined and ignored, and yet being completely unaware that you're doing it in the moment.

To be alienated from the world of faces is a strange and estranging position to be in, but I'm comforted by the thought that articles like this will do a little to help people forgive me and others like me.

Take the test

Drs Richard Cook, Punit Shah and City University London and Kings College London have come up with a 20-item questionnaire, external to help measure the severity of someone's face blindness.

Each question is scored out of five, giving a total score of up to 100, but the abridged version below, created with the help of Dr Shah, gives a score out of 50.

The test is a guide and cannot tell you definitively whether you have face blindness or not.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published4 November 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published6 October 2013