Credit card sexism: The woman who couldn't buy a moped

- Published

When the first British credit card launched 50 years ago it was mostly used by men

In the 1960s and 1970s, women were viewed as a riskier investment by banks and stores

Women had to get their father or husband to sign for most loans even if they earned more than them

Christine Edwards describes the discrimination she faced in Britain 40 years ago

Christine Edwards was 23 when she decided to buy a moped to ride to work.

"There was one for sale at a local dealership - one where you pedalled before the engine kicked in. I had saved the 30% deposit and wanted a hire purchase agreement to cover the balance."

However, the salesman said Edwards had to get her father's signature to secure the contract.

"I explained my parents were divorced and I wasn't in contact with my father but they wouldn't change their minds. They refused to take my mother's signature," she says.

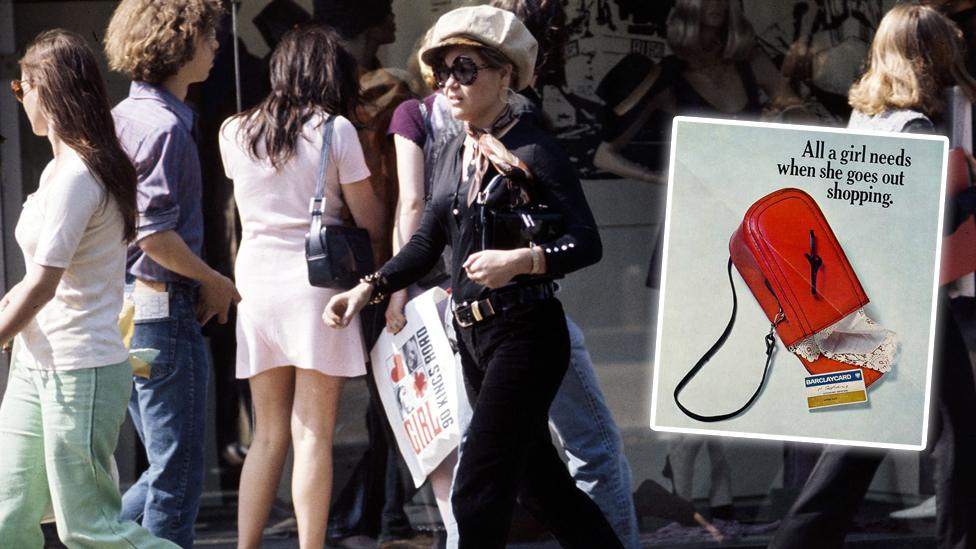

Shoppers on the Kings Road in Chelsea in 1970 and a Barclaycard Advert from 1973

This was Britain in 1970 - just a generation ago but a world away in its attitude to women.

"There was still this mindset that women got certain rights through the relevant man in her life," says Prof Lucy Delap from Cambridge University.

"Women had long been in charge of household budgets, but it was the husband who gave his wife the housekeeping money and held the financial power."

Women had an increasing amount of purchasing power. In 1951 about 36% of women aged 20 to 64 were in work. By 1971 this had risen to 52%, but women were still considered second-class citizens by lenders.

Susan Woolley, from Chester, who earned a third more than her husband, ran into problems.

"I wanted to buy a three-piece suite on hire purchase soon after I got married," she says. "But I had to get my husband's signature even though I earned £13 per week while he earned £10 a week. I was extremely annoyed."

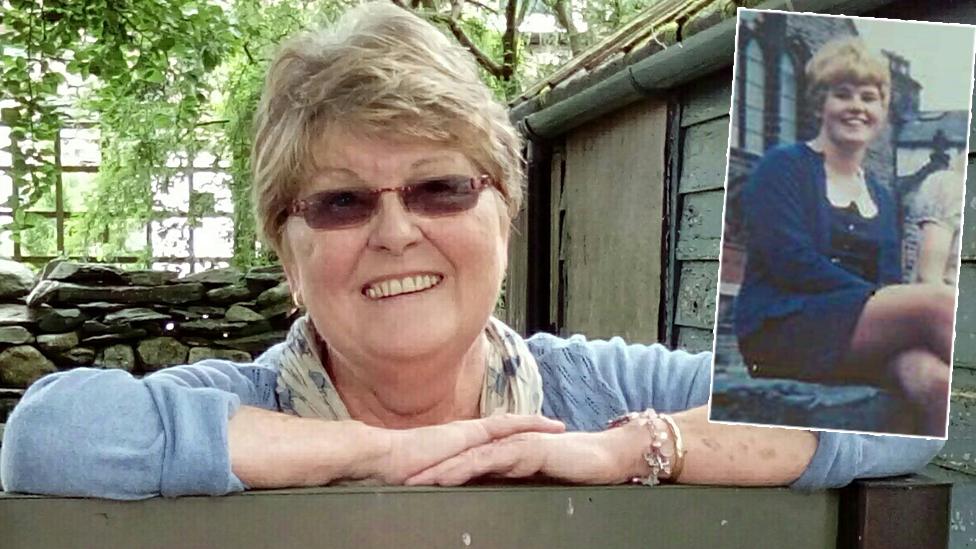

Susan Woolley earned more than her husband, but wasn't allowed to sign for a hire purchase

While women were fed up with attitudes out of step with reality, few were prepared to take on the conservative culture.

"We'd grown up in an environment where poor treatment was accepted," Edwards says.

"We were used to it. Don't forget that at this time all the boys earned more than what we did for doing the same job. It wasn't until those wonderful women at Dagenham went on strike that we realised we could do something."

Industrial action by women at Ford's Dagenham plant in 1968 led to the Equal Pay Act of 1970. Five years later the Employment Protection Act introduced statutory maternity pay and job reinstatement rights.

Yet everyday financial discrimination continued.

Kath Dawson got her first credit card in 1973 - the year Barclays started promoting them to women

Kath Dawson, from Bury, says: "We needed a washing machine and I saw an ex-display one in a shop. I went to buy it on hire purchase but I was told my husband had to sign for it.

"I had to plead with the staff to allow me to take the paperwork home to get his signature as he worked in a different town. It meant the washing machine was in his name even though I made the payments."

She later decided to sign up with the AA in case the car broke down and filled in the form, putting herself as the principal driver.

"When the membership cards came through my husband was named as the full member and I was the associate member even though I had paid for it."

The credit card, first introduced to the UK by Barclays Bank 50 years ago, represented a break with the past. While it wasn't actively marketed at women for the first five years, a woman didn't require a male guarantor to sign her application.

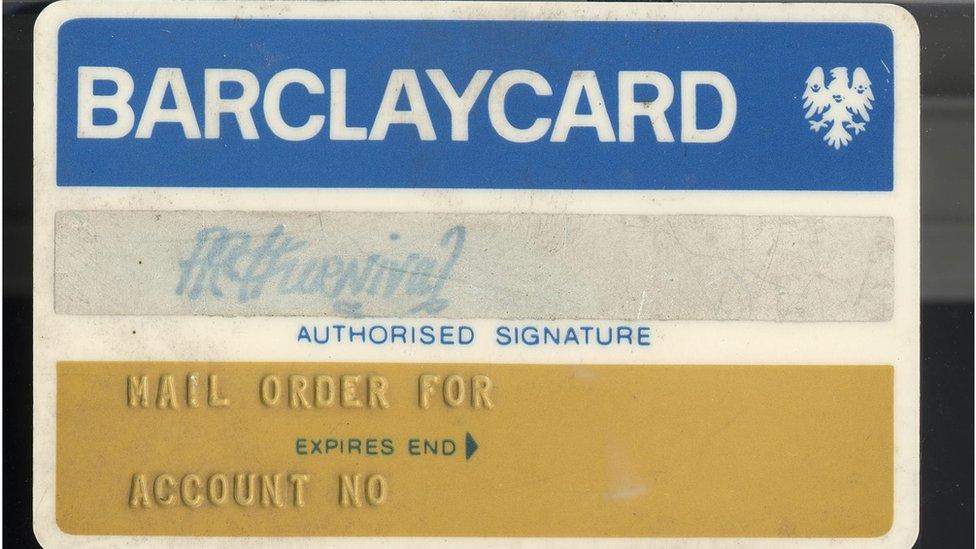

The first Barclaycard was produced in 1966

"I got a credit card when they first came out in 1966," Catherine Petts says.

"I was a graduate with a degree in economics, working in the finance industries. I got one because I thought I looked quite sophisticated using it in shops!"

Dawson got her first credit card in 1973, the year that Barclays began actively promoting them to women.

"I got it to help balance my finances and I didn't need a male guarantor. I was afraid of using my credit card when I first got it. I had it for emergencies."

A look back to when men were assumed to hold all the financial power

The Sex Discrimination Act of 1975 finally outlawed discrimination against women seeking to obtain goods, facilities or services, including loans or credit.

However, a news report in the Times in 1978 revealed some retailers were still asking for male guarantors.

"In the end it was the economy that drove the change," Delap says.

"In the 1970s banks and retailers could use the excuse that fluctuating interest rates made it difficult to lend in general.

"But they couldn't use that in the 1980s. The government was telling banks to lend more to stimulate growth and credit card use boomed."

Sheena Fraser started working for a bank as a teenager. She wore a suit like the male staff instead of the overall given to female staff as a protest

However, some women found it impossible to get a credit card because of financial discrimination they had faced in the past.

Sheena Fraser, who worked for a bank in the 1960s, says her staff current account was transferred to a joint account while she was on honeymoon.

"It said 'Mr (my husband's name) and another' and they also changed my contract to temporary staff.

"I later realised I couldn't build up a credit rating of my own because I was the second person named on the account, as well as on rents, loans, mortgages and so on. So getting a credit card in my own name still eludes me.

"My widowed friend faced the same problem. Her husband's credit card was withdrawn immediately on his death and she had difficulty getting her own card without a credit history.

"Gender discrimination back in the 60s and 70s still has ramifications for women today."

Find out more

Follow Claire Bates on Twitter @batesybates, external

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external