The 18 sewer men who changed the war

- Published

The Somme mining was spectacular but not a spectacular success

The Somme is remembered for slaughter with men machine-gunned in their tens of thousands. But it also featured a bold attempt at breaking the deadlock - a form of warfare revolutionised by an unlikely group of British sewer workers.

The giant Lochnagar Crater, south of the French village of La Boisselle, has never been filled.

The chalky soil of the 300ft diameter depression is now covered in grass and is overlooked by a wooden cross which stands as a memorial to all the dead in the bloodbath that was the Somme.

But this hole is also testament to an attempt to master the art of mining and reinvent it for the age of the machine gun. A 1,000ft tunnel was filled with 27 tonnes of ammonal explosive and the resulting explosion threw debris 4,000ft into the air.

It was the largest of the series of mines [the total is variously recorded as either 17 or 19] laid across the line of the Allied attack that day. The series of blasts was at that point the largest manmade sound ever made.

The revolution in using tunnelling for war had started in February 1915 with the formation of an extraordinary underground unit.

The first 18 men were not typical Army recruits.

Many were over 40. A few were white-haired and toothless. Most were small - less than 5ft 4in tall, at a time when the average height was 5ft 8in. They had strong backs and calloused hands.

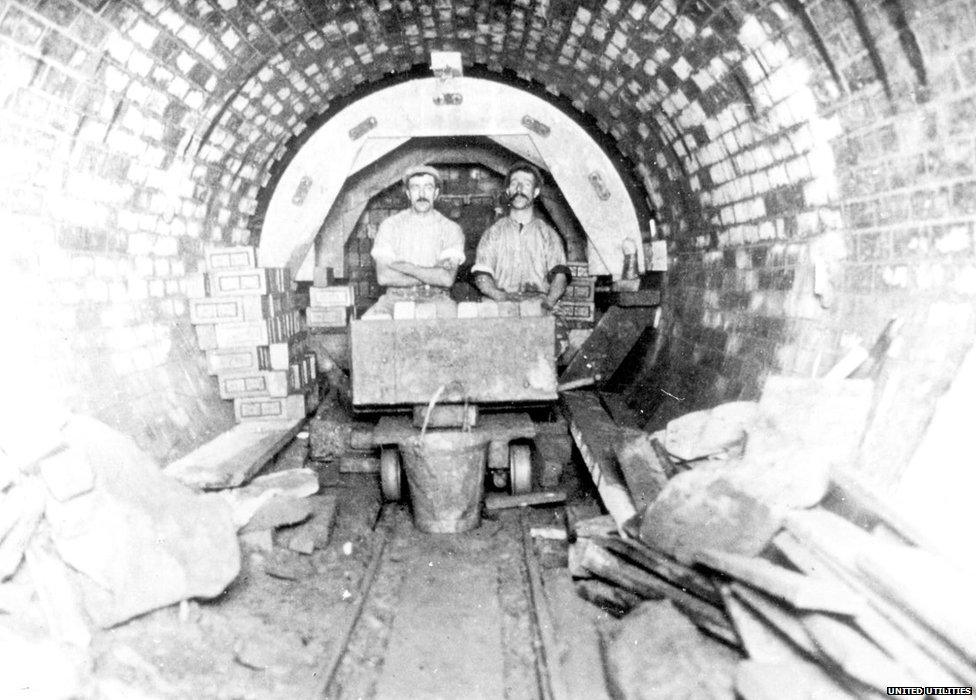

Manchester's Edwardian sewer builders - pictured south of the city under Didsbury in 1912

Although in uniform, they looked dishevelled. They couldn't march, drill or salute, and were more likely to call an officer "mate" rather than "sir".

The Manchester Moles were sewer men and they could dig four times faster than their German rivals.

The men became the founding members of 170 (Tunnelling) Company, Royal Engineers. Their pioneering work was the beginning of more than 3,000 miles of tunnels in France, Belgium and Gallipoli.

In a defensive war, both sides tried to dig under each other's fortifications to blow them up from beneath. And both sides tried to destroy each other's tunnels.

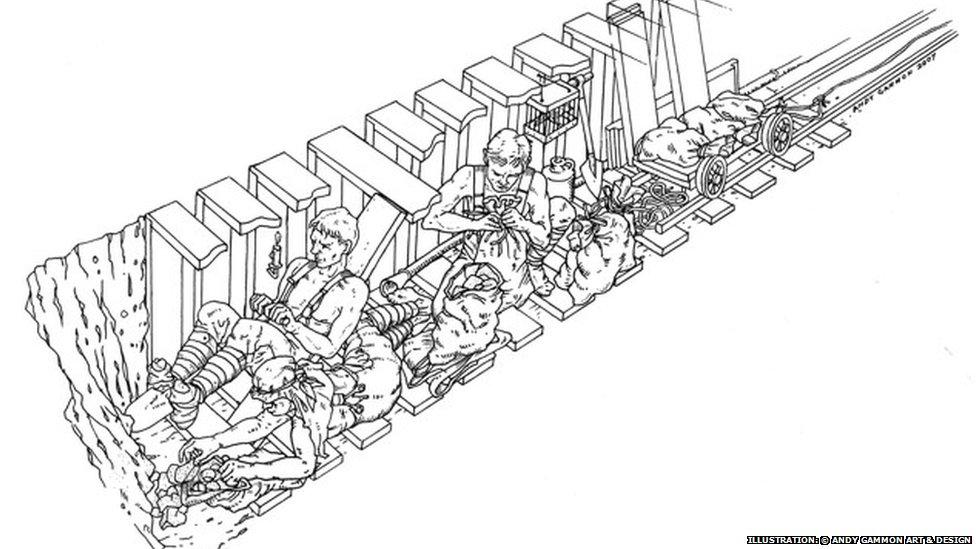

Clay-kicking demonstrated

While the horror of the trenches has been well documented, what happened beneath the battlefields - in the foetid, dark, cramped, and frequently wet tunnels - is less well known, and arguably far more frightening. While stalemate reigned above ground, a secret and often frantic subterranean war raged below.

There, the thunder of the surface war was deadened. Shellbursts were merely a faint thud, and the clatter of machine-guns and shouting of men was entirely inaudible. Here, however, one's ears were more important than one's eyes.

At the end of a gallery, surrounded by still, damp earth, tunnellers listened. For a scrape, a knock, a voice… even for a sneeze. The enemy might be 50 yards away, or a couple of inches.

The slightest noise could bring terror. You either had to run, or set a charge, move back and hope that it was the other man who would be entombed, torn apart, crushed or gassed - even drowned.

The British tunnelling masterplan was largely down to one extraordinary and rather eccentric man. Major John Norton-Griffiths, then MP for Wednesbury, had already earned the nicknames Empire Jack and Hell Fire Jack for his devotion to the British Imperial ideal.

He'd even raised a colonial corps of old fighters at his own expense before Britain had formally gone to war.

"He was an entrepreneur, a go-getter - not a glory seeker, but the type of man who didn't sit on his hands and liked to get things done," says Tony Bridgland, author of Tunnelmaster and Arsonist of the Great War: The Norton-Griffiths Story.

The larger-than-life character was soon renowned for touring the trenches in a Rolls-Royce loaded with cases of port.

John Norton-Griffiths had various nicknames including Empire Jack and the Angel of Destruction

When war was declared, his engineering company Griffiths & Co were working on a contract to extend Manchester Corporation's drainage system. But Norton-Griffiths believed his specialist sewer-drivers possessed a skill that would give the British an advantage in Flanders.

The Manchester geology was similar to that of Flanders - heavy clay. Rather than using picks with their arms to tunnel through the clay his men employed the far greater power of their legs.

Their technique - known as "clay kicking" or "working on the cross" - involved a man sitting with his back supported against a wooden rest (the cross) and pushing a small, razor-sharp spade-like implement (a grafting tool) into the clay face before him.

It was not only quick and efficient, but quiet.

Norton-Griffiths became convinced that clay-kicking could be a useful weapon on the Western Front.

Persuading the War Office and the Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener - a family friend - to regard his idea as anything other than absurd however, was another matter.

After the Germans blew their first underground mines killing a number of Indian soldiers and creating panic for miles, he wrote asking if "a handful of Moles" - as he called his Manchester men - could be sent to France. The letter was filed under "M", but ignored.

But Norton-Griffiths was nothing if not persistent.

By January 1915, and after more costly explosions, it was clear that the Germans were beginning to mine systematically.

The British were unable to respond, for, in the belief that siege warfare tactics like this were a thing of the past, the Royal Engineers had wound down their military mining section. There was consternation at the War Office.

On 12 February 1915, Norton-Griffiths received a telegram from Kitchener asking for advice.

"Norton-Griffiths barged into Kitchener's office, grabbed a shovel from the grate, went down on the floor on his back, threw his legs in the air and began furiously shovelling imaginary earth between his feet to demonstrate clay-kicking," says his granddaughter Anne Morgan.

"He wasn't always the most politically correct man - he was impatient, of a rebellious nature and went on to bribe commanding officers of different companies to let him have their miners by getting them drunk on fine port - but he was certainly charismatic."

Kitchener was convinced. He asked for 10,000 Moles - immediately.

Men at work on Manchester Corporation's drainage system

Norton-Griffiths said he didn't think there were that many in the nation, but straight away rushed to France with two employees to establish the suitability of the ground.

On arrival, his manager and works foreman, 35-year-old Norman Richard Miles, told his boss the clay was "so ideal it made his mouth water".

A trial was agreed, and Norton-Griffiths wasted no time getting his men to the front line. The next day, 20 Manchester sewer men found themselves London-bound.

Eighteen passed the medical and were sent to Royal Engineer HQ at Chatham in Kent, to be enlisted as sappers.

Two days later the men arrived in Bethune, less than 15 miles from Givenchy. The village and nearby sectors were to be their home for most of the next three years. The tunnelling companies had been born.

Frederick James Carrington was living in Manchester with his wife and his two-year-old daughter when he swapped sewers for tunnels - he survived the war

The original 18 men were divided into two sections which were augmented by infantrymen with mining experience drawn from nearby battalions. Officers were assigned, and the entirely inexperienced crew began digging.

Military historian Jeremy Banning, external says even though the sewer men were used to working underground, the sudden shift from Manchester to the bloody French battlefields would have been overwhelming.

"These men had changed from civilian to military in a matter of days, when the average infantry soldier at that time would have had nine months of training to drill, get physically fit, and learn the rules of order and obey.

French and British troops in a trench on the Western Front during WW1

"They also weren't used to having a silent enemy that could strike at any moment. The mental anguish and the strain on their nerves would have been testing, especially in the grim conditions at Givenchy."

Underground warfare was a 24-hour business - shifts worked eight hours on, 16 off. The Givenchy tunnels were very wet, claustrophobic and constricted, typically measuring about 4 ft 6in (130cm) by 2ft 3in (69cm).

"A clay-kicking team," says Peter Barton, author of Beneath Flanders Fields and designer and instigator of The Tunnellers Memorial at Givenchy, "consisted of a kicker, who silently prised out clay "spits" at the "face", a bagger who quietly put the spits into sandbags, and a runner who put the bags on a small trolley on rails which led back to the shaft.

A heavy shell exploding during the Battle of the Somme

"The team periodically changed places. Filled bags were hoisted up the shaft and dumped on the surface to give extra protection to the men in the trenches."

"Tunnelling at Givenchy, where the clay was mixed with sand and gravel, was extremely difficult," he says.

Despite this, the men could advance an average of 26 ft per day. German tunnellers managed less than 7ft in 24 hours.

Back in London, the War Office issued requests for ex-miners serving with infantry units to urgently transfer to tunnelling companies.

Norton-Griffiths believed experienced older men were the best for this highly stressful task, for they were likely to be "steadier" under pressure, and not panic in an emergency.

One war diary entry records: "Sewer men of the type of [his manager and works foreman] Miles are very limited and at all times are difficult to get, and for permanent supplies we have no other course but to fall back on the Miners."

Professional mineral, slate, and coal miners from across the UK, and indeed hundreds from every corner of the British Empire, had soon been signed up.

The enticement of six shillings a day - a decent wage for working men at that time - was a powerful incentive. By contrast, an unskilled tunneller's mate received two shillings and tuppence, while the infantryman in the trenches pocketed a meagre one shilling and threepence.

Men above ground had no idea if the Germans could be tunnelling beneath them

The company soon began four separate tunnel schemes in places where the Germans were already mining - the underground war had started.

170 Tunnelling Company diary entry on 3 April 1915:

"Charges were put in the ends of galleries and exploded, blowing up a strong point in the enemy's line... In the meantime the Germans had started a counter-mine, but we managed to blow up their trenches bringing down the front half of a brickstack which had been hollowed out and used as a sniper's post. One of the snipers could be plainly seen when the smoke cleared away pinned in up to his middle by the fallen bricks."

With the two sides working in such dangerous conditions and in such close proximity, it wasn't long before the Manchester Moles suffered their first fatalities.

The Germans would also detonate mines in shallow open tunnels

It's hard to be certain how the first of Norton-Griffiths' sewer workers died, but the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records and the tunnelling company's war diary suggest that a sapper called William Stafford was killed by a German mine on 21 April 1915:

"When driving further branch galleries for attack purposes, we heard the Germans working a counter mine near one, and exploded a small charge to destroy his work. The Germans put very large charges in their counter-mines and destroyed our forward galleries, besides blowing up a considerable portion of their own trench. Two of our men were killed underground by the explosion."

Just a few days later, an officer suffered a similar fate after a delay in detonating a mine at Givenchy led to the Germans blowing their mine first. A 24 April entry at the Orchard workings in Givenchy reads:

"Sounds first heard at 1pm of dropping tools and talking. Action taken by 2/Lt Barclay was to build a barricade against the crater end of our tunnel and to send for Colonel Boardall. This officer was over at Cuinchy and the message did not reach him at once. He arrived at the site between 5 and 6pm and instructed Lieutenant Barclay to construct another barricade 4ft this side of the original one, leaving sufficient space at the top for the [gun]powder to be passed through. He himself came down to arrange about getting a charge ready.

"Before the second barricade was quite completed the Germans blew a mine killing Lt. Barclay and 6840 Lance-Corporal Bishop, 2nd South Staffordshire Regiment attached to 170 Coy. RE. This happened at 9.30pm."

Craters were fought over by the two sides

A sea of craters was gradually formed between the opposing trenches. If a crater could be incorporated into one's trench line, it could prove very valuable. They were always fought over.

For Norton-Griffiths' former sewer foreman, returning to the scene of an explosion on 24 April, again at the Orchard, ended in him paying the ultimate price:

"2/Lt Lacey and 2/Lt Martin who had gone up with Lt Boardall to assist in laying the charge then went out with a patrol of the IG sent to OC section to see if the crater was occupied and found it empty. Sp 66877 Sergeant Miles RE, who had accompanied this patrol, went out again with a second, which was to occupy the crater. The Germans had meanwhile occupied it and shot him dead."

In a roll of honour notice, Miles's commanding officer is quoted as saying he had to prohibit the men from extricating his body to bury him, despite them being "very anxious" to do so. He said:

"Having inspected the spot I was reluctantly compelled to forbid them to do so, as it would not have been possible without a very grave risk of losing further lives in the attempt. His body lies buried under about 15 feet of earth half way between our trenches and the German trenches in the orchard just east of Givenchy."

![[Norman] Richard Miles](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/224/cpsprodpb/15CAB/production/_90195298_richardmiles.jpg)

[Norman] Richard Miles

The most common killer, however, was carbon monoxide poisoning - generated in large quantities by every explosion. It was invisible and odourless.

"Tunnellers could lose consciousness or control of their limbs in a matter of minutes, so they had to act fast after an explosion. If they were working underground and the shudder of a blast was felt, everyone would race for the shaft to get out into the fresh air before the gas got into their bloodstream," Barton says.

As an "early warning system", like coal miners, tunnellers carried caged canaries underground. "If a canary fell off its perch, gas was present," Barton says.

Clifford Maher, 74, from Cheadle Hulme, near Manchester, says his grandfather Sapper Stephen Ranson - who had worked as excavator for the Water Board before he became one of the original 18 men in 170 Tunnelling Company - was gassed twice in Flanders. In each instance it took a considerable time to recover.

"His tunnelling experience didn't put him off working as a ganger though. After he came back from the war he continued to work on contracts like Merseyside all round the country. He was quite well paid I think, not short of a bob or two," he says.

The Western Front soon became a shell-cratered landscape

170 TC had soon distinguished itself in some bitter mining contests.

Sapper Thomas Welsby, a 44-year-old father of five, and again one of Norton-Griffiths' originals, was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal Conduct (DCM) for "conspicuous gallantry and ability" at Cuinchy on 28 June 1915. The London Gazette records:

"Whilst clearing a gallery which had been damaged by a German mine, he made a hole into the enemy's gallery accidentally, this he at once blocked up with sandbags and laid a charge against it. Our mine was successfully fired, destroying the enemy's gallery, and exploding the charge which they had laid."

Enid Forshaw says her family was always told how brave Sapper Thomas Welsby was

His granddaughter, Enid Forshaw from Stockport, says the family was always told how brave he was:

"I think he specialised in laying and defusing bombs and mines in the tunnels, which sounds skilled but was also incredibly frightening. He died in shellfire in 1917. My father said it was a struggle for his mum to bring up the children on her own."

The same week, fellow Manchester Mole Sapper Dennis Murphy was awarded the DCM.

A supplement to the London Gazette recorded: "During the operations of a German working party at the end of a 200-foot gallery, Sapper Murphy, with two other men, listened to and noted the progress of the work, and ultimately placed 200 lbs of gunpowder and over 400 sacks of tamping at the end of the gallery, working at the highest speed in bad air, when the slightest noise would have cost them their lives. He showed a splendid example of devotion to duty."

In August 1915 Captain Lacey, who'd been attached to 170 TC since the first moles had arrived at Givenchy, was killed in an explosion with six of his men in a tunnel in the neighbouring sector of Cuinchy.

The 28-year-old had already received the Military Cross and just five days before had been promoted to the rank of captain.

"The last few months of 1915, when 170 TC was working in a deadly sector known as the Hohenzollern Redoubt, was probably the most hostile period for the company, with mines being blown up every other day," says Banning.

"The Germans and British were about 50 to 100 yards apart, with each trying to seek the advantage. There was an overlapping mass of mine craters between them - it would have been hell on earth," he says.

The crater created by a mine blown under a field on the first day of the Somme

The geology of this sector was different, however - it was chalk rather than clay.

"This would have suited the men with coal mining skills - ex-coalminers that had been transferred from infantry battalions - because coal has similar properties to chalk. So the clay-kickers would have had to pick up new skills from them. Instead of working on the cross, they'd have had to use short picks or even prise out lumps of chalk as quietly as possible with a bayonet," he says.

Despite the British tunnellers soon seizing the initiative underground, the Germans always remained superior at crater fighting, according to Banning.

An extract from 170 TC war diary on 18 March 1916 shows how hostile it could be:

"Germans made a very strong attack on Crater Nos. 2, A, B & C at 5pm. exploding a small shallow mine East of No.2 Crater and another north of C Crater, both doing only very slight material damage. Our men were all caught in the crater by the bombardment. 1 NCO and 1 man retrieved from C Crater. 15 RE's and 20 attached infantry missing. The Germans gained crater 2, A, B & C, and we now have bombing posts looking into Nos 2 B & C."

By the middle of 1916 the number of British tunnellers had risen to about 25,000, but they were vitally assisted by almost twice that number of "attached infantry", soldiers who worked permanently alongside them as "beasts of burden", fetching and carrying equipment and timber, pumping air and water, and removing spoil.

The German troops would attack following the explosion of a mine

With such long periods in dark, damp and cramped conditions, many men became ill. When the mental stresses were added to the physical effort, the work could be desolate and debilitating.

Alcohol was an important part of many tunneller's lives, used a release valve for the constant state of anxiety. Courts martial for drunkenness were far from uncommon.

Another original clay-kicker, 40 year-old Sapper Charles "Chas" Williams, was sentenced to 21 days "Field Punishment No 1" for drunkenness in February 1917.

This involved being tied to a fixed object, often a wheel, for up to two hours per day.

Fellow sewer worker sapper Frank Jameson also received seven days of this treatment for getting drunk and going absent without leave for two days in November 1915 - he forfeited two days pay as well.

"Very few tunnellers lasted the whole war, it was too great a strain on their body and their nerves, for every moment spent working underground could have been their last," says Banning.

Five of the 18 Manchester sewer men received the Silver War Badge, issued to service personnel who had been honourably discharged as a result of wounds or sickness.

The prime tunneller duty was to protect the infantry in the trenches from being undermined

The sterling silver lapel badge was intended to be worn on civilian clothes back at home, to avoid the wearer being presented with white feathers, usually by "dutiful" women to shame apparently able-bodied young men not in uniform to go to war.

The large mining operation before the Somme assault which left the Lochnagar Crater was not a resounding success. But lessons continued to be learned and the very next year mining warfare reached its zenith.

On 7 June 1917, 19 huge British mines were exploded beneath the Messines Ridge in Belgian Flanders. The blasts killed as many as 10,000 soldiers and shattered German morale and enabled the British to capture the enemy positions within hours.

The explosions were said to have been heard by the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, 150 miles (241 km) away in 10 Downing Street. The attack was one of war's few unalloyed successes.

Again, the idea for these huge multiple blows came from John Norton-Griffiths, who first put forward the audacious proposal two years earlier in 1915.

When the war ended, 12 of the 18 original Manchester Moles had survived.

Barton believes WWI was truly a war of engineers. "The Mancunians were the starting point for a colossal scheme of military engineering," he says, "and it would be impossible to say what would have happened underground on the Western Front without the dogged determination - and a shameless disregard of the rules - of John Norton-Griffiths."

The most unlikely heroes of all, however, were the motley crew of Manchester sewer men.

"Suddenly sewer men that at home might often have been looked down upon as grubby, rough and ready industrial types were the most prized troops on the Western Front," says Banning. "They are unsung, but worth their weight in gold, and they should be remembered accordingly."

The memorial, external to them can be found in the village of Givenchy - where the underground war started.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.