The fight to celebrate great women on Britain's streets

- Published

Statues across the UK are predominantly of men, but campaigns to memorialise important women are increasingly meeting a receptive audience, writes Mark A Silberstein.

Fewer than one in five listed statues are of women

Campaigns for more are gathering support

Two significant unveilings last month alone

On a cold overcast day, in the town centre of Sheffield, a statue dubbed "Women of Steel" is unveiled to a packed crowd. The memorial, depicting two women dressed in boiler suits, celebrates the work of women in steel mills throughout both world wars.

One-hundred-and-forty-one of these "women of steel" are still alive today.

Barbara Bell joined her mother in the steel mills during World War Two

The youngest, Barbara Bell, 85, is at the ceremony. She started working in the offices of the steel mill at the end of World War Two at the age of 14.

"I can remember when I used to go down and walk through all those hot mills and those women were there and they were doing a man's job. It was just wonderful really and this all brings it back and makes it worthwhile."

Bell's eyes light up from behind her glasses as she speaks of the unveiling, but she wishes her own mother, and the other women of steel could have been here to see the statue: "If they had been recognised while they were here it would have been wonderful wouldn't it?"

According to journalist and feminist activist Caroline Criado-Perez's research, of the 925 statues listed in the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (PMSA) database only 158 are of a woman as a lone standing statue.

Besides the numerous statues of Queen Victoria that dot the British landscape, many memorials to British women are nameless sculptures, typically rendered as naked, curvaceous and reclining.

The inVISIBLEwomen website, which campaigns for civic statues of women, notes the difference between depictions of men and women in public spaces: "… female figures are largely semi-clad, often reclining, and typically depict a maternal, saintly or sexualised image of womanhood, rather than worldly achievements."

In the Oxford Dictionary there is a distinct difference between the term statue and sculpture, statue meaning "a carved figure of a person" and sculpture a "two- or three-dimensional representative or abstract form".

In Birmingham, a water feature called The River Goddess Fountain has been nicknamed the "Floozie in the Jacuzzi", external.

In Manchester, a lack of women statues led Labour Councillor Andrew Simcock to hold a public vote on which famous local woman should be commemorated. Of the 16 choices the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, who was born in Manchester, won hands-down with 53%.

Sole sister: A statue to Emmeline Pankhurst stands outside the Houses of Parliament in London

Simcock says: "There are 17 statues of public people in the city but 16 of them are men and the only woman is Queen Victoria."

The statue of Pankhurst is expected to be erected in 2019 with the funding coming from crowd-sourcing.

In the past two years support has been growing for women statue campaigns across the UK including in places including Glasgow, Liverpool, London, Manchester, Middlesbrough, Belfast and Sheffield.

Campaigns for women's female statues are not a new thing but the difference now is campaigners are being listened to by high-profile figures.

Before the London mayoral elections this year, both the candidates, Sadiq Khan and Zac Goldsmith, pledged to become patrons of the Mary Seacole statue on the outcome of either one winning the race.

Councils across the country have also become more involved. Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour party leader, and Education Secretary Nicky Morgan, are backing the Mary on the Green Campaign, in London, which is trying to get a statue of author and women's rights campaigner Mary Wollstonecraft erected on Newington Green, near where she lived.

Mary Wollstonecraft was a prominent women's rights campaigner in the 18th Century

Chairwoman of the Mary on the Green campaign Bee Rowlatt says: "Currently nine out of 10 London statues are of men, so school girls who walk around the streets of London and look up don't see women on pedestals… and it's time to fix that."

In 2004 Mary Seacole won the title of the greatest black Briton for her work helping British soldiers in the Crimean war. Last month, a statue of her was unveiled in London, outside St Thomas' hospital.

In 1854 Seacole's offers of being sent from London to the battlefront were refused. So, the black nurse from Jamaica made her own way to the peninsula's battlefields, where she looked after British soldiers wounded in the fighting.

Lord Soley started the campaign for her statue more than three decades ago, when a group of nurses who admired Seacole's work approached him:

Mary Seacole's statue was unveiled opposite the Houses of Parliament last month

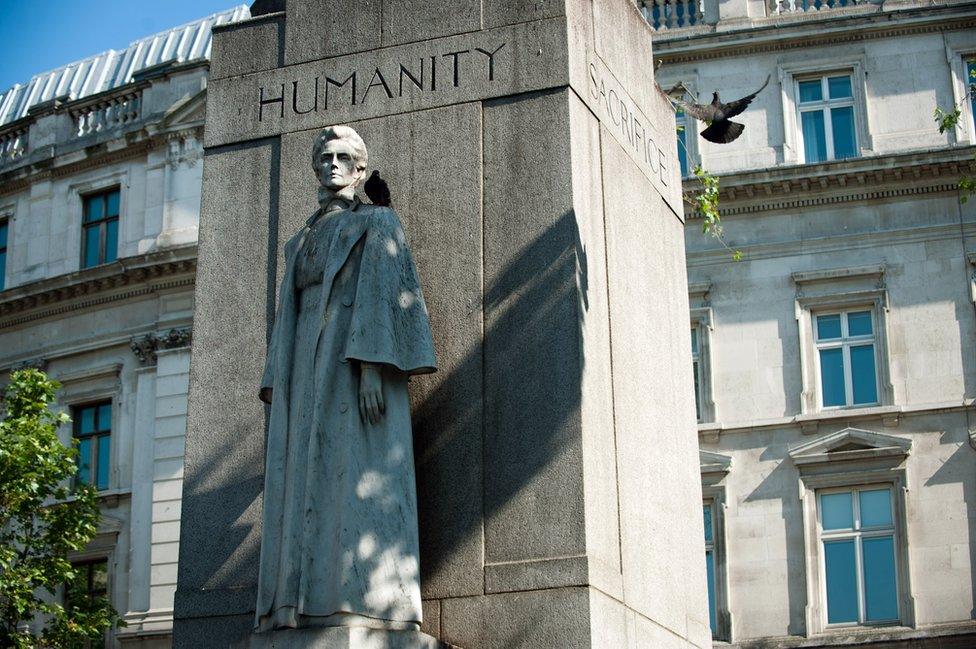

Still, standing: A statue to Florence Nightingale - part of the Crimean War Memorial in St James's, London

"It goes back a long way, I was approached by a group of women who had been born in the Caribbean but who had come over to fight for Britain in 1939, 1940. I was very naive actually, I thought the campaign would be fairly quick and easy," says Soley.

He has spent a large part of his life pushing for the Mary Seacole statue to be made. Soley encountered opposition from a campaign in defence of the legacy of Florence Nightingale - who was in Crimea at the same time as Seacole. Nightingale's defenders question Seacole's medical training and say she had never set foot inside St Thomas' hospital - outside which the statue has been erected.

It's not just campaigners and humanitarians who are benefiting from the closing of the granite gender gap. Statues of female entertainers have also been on the rise, challenging the tradition of the unnamed female reclining figure.

These entertainers have been depicted with their well-known traits, such as the statue dedicated to the late singer Amy Winehouse, in London, with her trademark beehive, and the bronze statue of post-war British film star Diana Dors, in Swindon, depicting her in an elegant ball gown and flowing locks.

A statue of Diana Dors stands outside the Cineworld cinema in West Swindon

In 2016, Cilla Black joined the long list of well-known entertainers who passed away.

John James Chambers, the founder of the Liverpool Beatles Appreciation Society, was the first to suggest that a statue should be dedicated to her, and now her sons are on the case.

Proposals for the statue are to depict her in a miniskirt outside the famous Cavern Club where she worked in the 1960s.

Chambers says he was moved by Cilla Black's rags-to-riches story: "She was brought up penniless. Her mother used to sell second-hand clothes and her father was a docker."

A statue celebrating the singer's life would be a fitting memorial, according to Chambers, "because it is something that lasts forever".

Other notable statues to women in London

Edith Cavell was a nurse shot by a German firing squad in Brussels in 1915 for helping Allied prisoners escape to Holland during World War One.

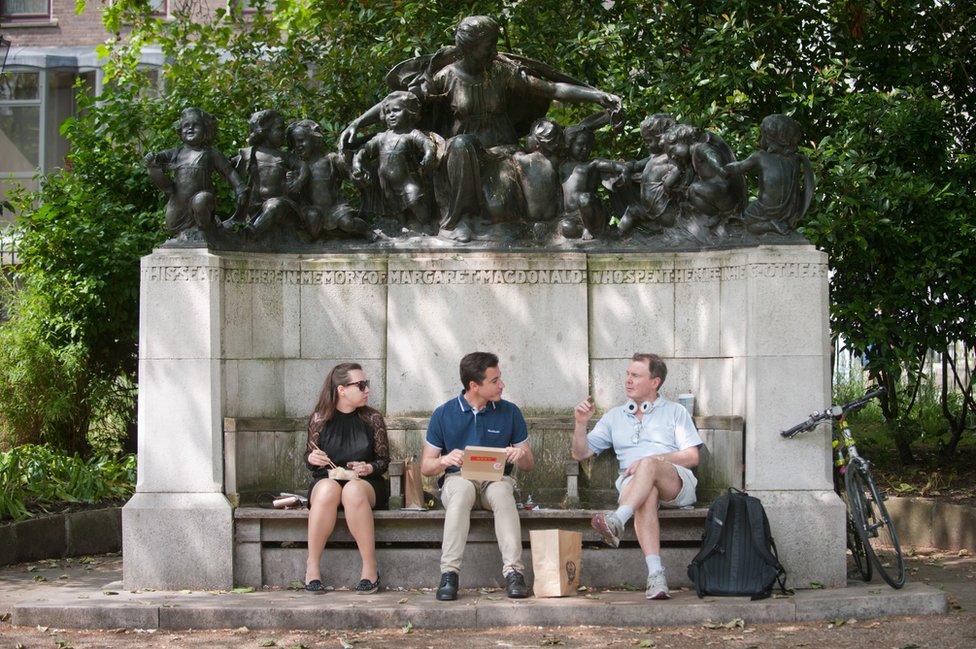

Solid-arity: Margaret MacDonald worked to improve the lot of women industrial workers and a member of National Union of Women Workers. Her husband, Ramsay MacDonald, became the first Labour Party Prime Minister.

Look a-cast: Virginia Woolf was a writer who helped shape post-Victorian Britain, influenced the course of literature, and continues to touch writers and readers the world over.

Violette Szabo was a member of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and twice parachuted into occupied France to aid the Resistance movement. On her second mission shortly after D-Day, she was captured, interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo. In early 1945, she was executed.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external