Can you get the benefits of exercise by having a hot bath?

- Published

We all know that exercise is good for us, but can you get the benefits without actually doing the exercise, asks Michael Mosley.

Having a hot bath or a sauna is a good way to soothe your limbs after exercise, but what happens if you do it instead of exercise? Dr Steve Faulkner of Loughborough University asked me to take part in an experiment comparing the relative benefits of having a long, hot bath versus an hour of hard pedalling.

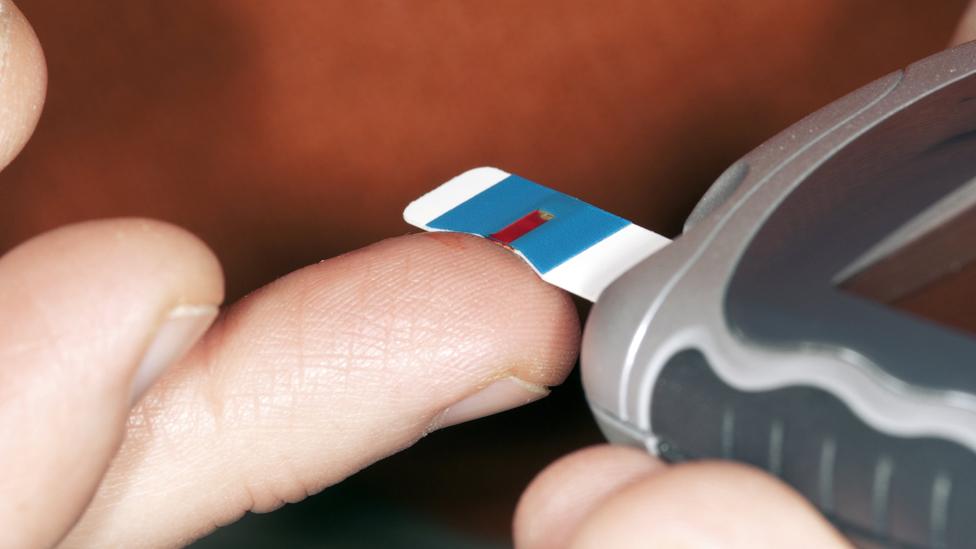

For this study I join a group of volunteers who have all been fitted with monitors which continuously record blood sugar levels. Keeping your blood sugar levels within the normal range is an important measure of your "metabolic" fitness.

We are also fitted with equipment to measure how many calories we burn and rectal thermometers to constantly measure our internal, core temperature.

The first part of the experiment is very relaxing, consisting of having a long, hot bath.

Going for the burn?

While I sit in the bath, which they keep at 40C, Steve closely monitors my core temperature. Once it has risen and stayed there, I am allowed out.

A couple of hours after my bath I have a light meal.

Since we want to see how having a hot bath compares with exercise we repeat the experiment, except this time instead of a bath it's an hour's sweating on a bike.

So what's the result?

"One of the first things that we were looking at," Steve says, "is the energy expenditure while you're in the bath and what we found was an 80% increase in energy expenditure just as a result of sitting in the bath for the course of an hour."

This is nothing like as many calories as cycling for an hour (which comes out at an average of 630 calories) but we do burn 140 calories, the equivalent of a brisk 30-minute walk.

But what about our blood sugar levels?

Testing for blood sugar levels

"Where we started to see differences," Steve tells me, "was when we looked at your peak glucose output."

Your peak glucose output is the amount that your blood sugar goes up after a meal. It's a risk marker for type-2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

"What we found," Steve says, "was that peak glucose was actually quite a bit lower after the bath, compared with exercise, which was completely unexpected"

In fact our volunteers' post-meal glucose levels are, on average, 10% lower after the baths than after the exercise.

But why does this happen?

Find out more

Trust Me I'm a Doctor: Summer Special is on BBC Two, 12 July at 20:00 BST - catch up on BBC iPlayer

Steve thinks that it may be partly due to the release of heat shock proteins which are, as the name implies, proteins released in response to heat. Their release can also be triggered by other forms of stress, such as infection, inflammation and exercise,

Heat shock proteins are part of your defence system. They help protect your body against damage, but animal studies suggest they may also help divert sugar from the bloodstream and into muscles. Keeping blood sugar levels down is important because persistently high blood sugar damages arteries and nerves.

Steve wouldn't suggest that having a hot bath or sauna should replace doing exercise and he recommends that people try to do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week. He sees this "whole body heating" research as being potentially most useful for people who struggle with controlling their blood sugar levels and who find it hard to exercise.

So getting hot turns out to have surprising benefits . But what about doing something called motor imagery? Can simply imagining yourself doing a particular exercise make your muscles stronger?

Motor imagery is not a crazy as it sounds. It's widely used by top athletes. To find out what effects it would have on a group of relatively sedentary Trust Me viewers we ask Prof Tony Kay from the University of Northampton to do an experiment.

Michael Mosley thinks about exercise

He starts by taking some base measurements. These include testing how strong their calf muscles were by asking them push as hard as they could against a heavy plate linked to sensors. Next he uses ultrasound to measure their calf muscle size. Finally, to assess just how much of their muscle they are actually using when pushing as hard as possible, he gives these muscles a small electric shock.

Once he's got his baseline measurements Tony asks the volunteers to spend 15 minutes a day thinking about the pushing exercise they've just done, imagining doing it.

So what happens? Well, much to my surprise, just thinking about exercising their calf muscle really does improve their strength. When we repeat the test a month later the group's calf muscles are, on average, 8% stronger.

It isn't because their muscles have got bigger (they haven't) - it's because by the end of a month of thinking about a particular exercise they are using more of the muscle fibres than they did at the start.

"They got better at recruiting the muscles in an orderly fashion," Tony says, "so they could activate a larger percentage of the muscle. That produced more force and so they became stronger."

Tony thinks that as well as helping top athletes, mental imagery could be a useful way to avoid losing strength if you're injured and can't exercise.

Trust Me I'm a Doctor: Summer Special is on BBC Two, 12 July at 20:00 BST - catch up on BBC iPlayer