What went on at the hospital that 'experimented' on child patients?

- Published

'He stuck a needle in my arm': How a child patient was forced to take the 'truth drug'

Dozens of people who were child patients at a psychiatric hospital in the 1960s and 70s claim they were experimented on with a so-called truth serum. It has left them with disturbing memories and troubling questions.

"I was your typical 60s teenager," says Marianne, a softly-spoken woman in her sixties.

Framed posters of musicians like Bob Dylan and John Lennon still hang on the walls of the living room in her quiet semi in Derby and a feathered dream-catcher twirls in the window.

"I liked fashion, I liked music. It was a good time to be young."

But Marianne's memories of the time aren't all so idyllic.

At the age of 14, she found out from a teacher that she was adopted. Things became difficult at home and after getting into trouble with the police, she was given probation and sent to Aston Hall, a "mental deficiency hospital" treating adults and children.

All that's left today of the complex in Derbyshire is a grand white house where the hospital's staff once lived. The site of the patient dormitories is being redeveloped to make way for new homes.

Find out more

The patient dormitories at Aston Hall

File on 4: What happened at Aston Hall Hospital? is on BBC Radio 4, 19 July at 20:00 BST - catch up on BBC iPlayer Radio

But before the hospital was demolished, a group of urban explorers photographed the derelict site and posted eerie photos online, external. Former patients like Marianne (not her real name) found the forum and started leaving comments about their experiences there.

They set up a support group for former patients, and more started coming forwards with troubling stories about the drugs they were given, the treatments they were subjected to and the long-term effects which still plague them today.

Pictures of the now-deserted Aston Hall hospital, posted on the Project Mayhem website

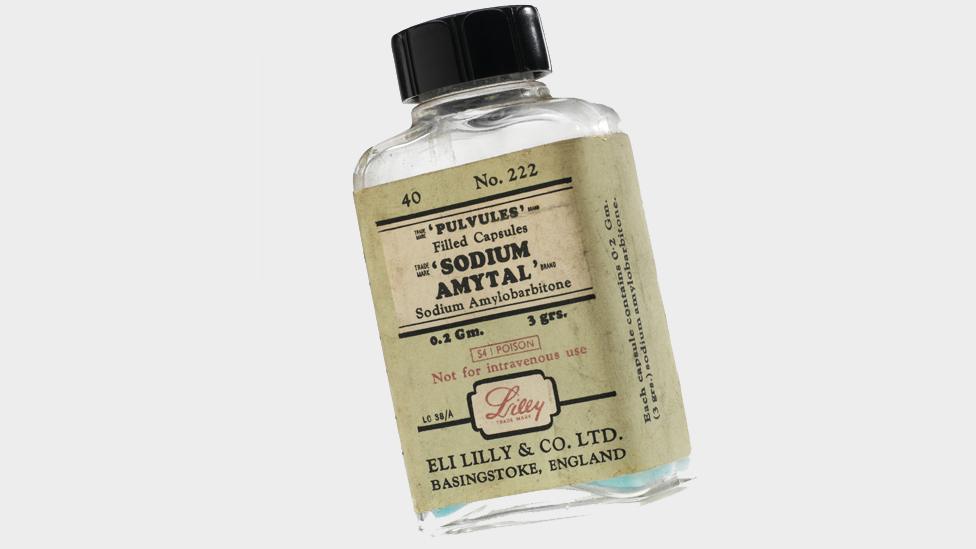

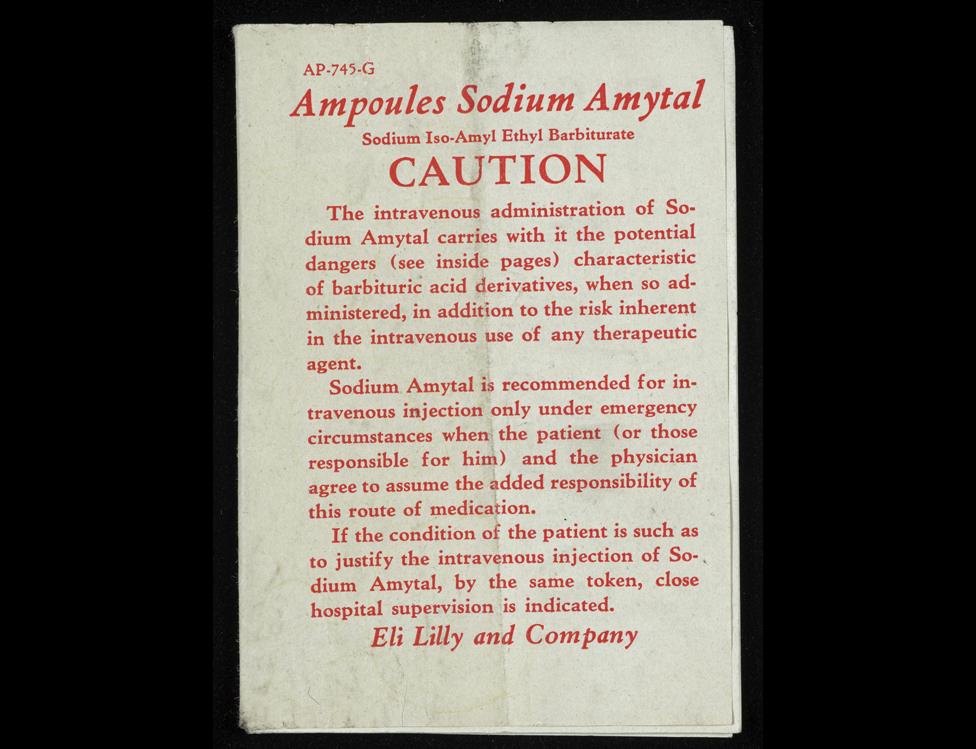

Many claim they were experimented on by the hospital's medical superintendent Dr Kenneth Milner using a drug called sodium amytal. It is known as a "truth serum" for its supposed ability to retrieve locked-away memories.

Marianne recalls a session with the doctor where she was stripped, made to wear a stiff white gown and told she would be asked some questions. Then he injected her with a drug that heavily sedated her.

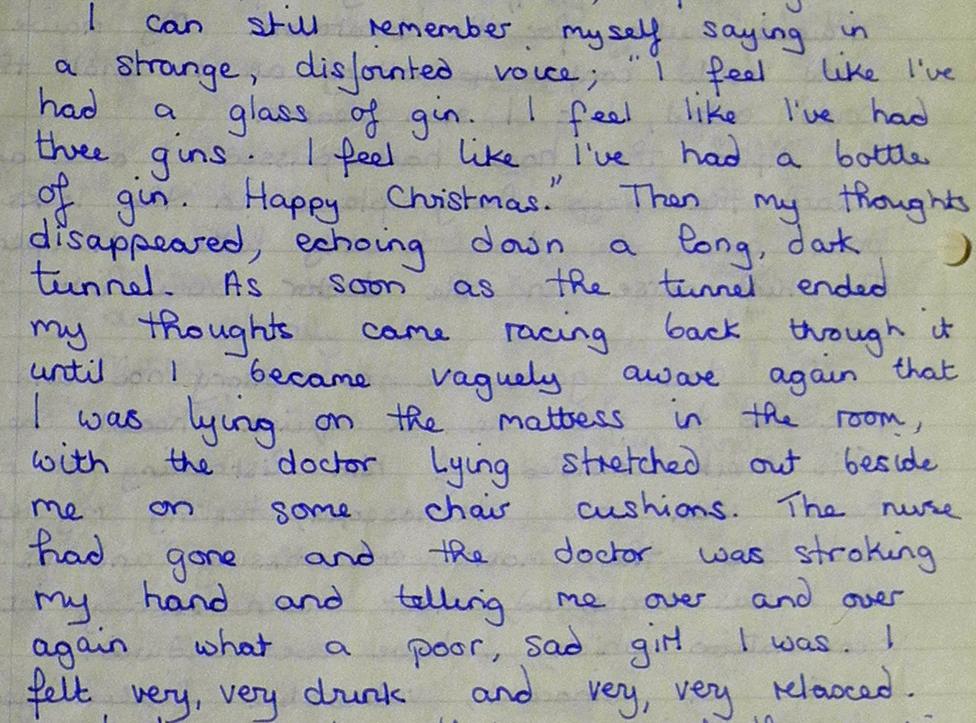

"I can remember equating it to being drunk and I was going: 'I feel like I've had about a bottle of gin, I feel like I've had about two bottles of gin'. And I can remember going: 'Happy Christmas, doctor'."

Her account is similar to those of other former patients at the time, who remember being locked in a small treatment room with a mattress on the floor. Some say their hands were tied with bandages before they were injected. Their medical records show the typical dose of sodium amytal was 60mg.

Standards of institutional care for children during the 1960s and 70s have come under close scrutiny in recent years, as accusations of abuse at the time have grown. So what was going on under Dr Milner at Aston Hall?

One expert believes Dr Milner was practising "narcoanalysis", a therapy used during World War Two to treat soldiers with shell-shock.

It was thought men who had experienced the horror of battle sometimes repressed what had happened to them. And this turned the trauma into severe physical paralysis or depression.

Traditional psychotherapy, where patients were asked to talk about their dreams in the hope of uncovering the hidden trauma, took too long. Soldiers were needed back on the frontline. So psychiatrists began using sodium amytal, which made the traumatised servicemen less inhibited.

Sodium amytal - the so-called "truth drug" - was thought to make trauma victims less inhibited about their suffering

Dr Norman Poole, a psychiatrist from St George's Hospital in London, sets out the theory: "Once you'd found this traumatic event and the patient was able to express this, then almost like a psychic abscess, you could prick it and the trauma, the grief, the emotions that were connected with it would come out and then the symptoms would resolve."

A 1946 documentary by the Hollywood director John Huston follows the rehabilitation of traumatised US servicemen, and shows narcoanalysis at work. In one scene, a soldier is treated with sodium amytal, questioned by a medic and then seen walking around the room unaided, having entered it unable to stand.

John Huston's 1946 documentary, Let There Be Light, shows a US serviceman being treated with sodium amytal

Narcoanalysis quickly fell out of fashion after the war, says Dr Poole, as alternative treatments emerged and psychiatrists became concerned about the lack of supporting evidence. However, evidence from Aston Hall shows it was being used into the late 1970s - not on grown male soldiers but vulnerable children and adolescents.

The UK's first-ever professor of child psychiatry, Michael Rutter from King's College London, was practising in the 1960s. The treatment, he says today, was not standard practice.

"As far as I knew nobody was using [sodium amytal] with children at that time," he says.

He is concerned by the use of the drug on children and the way it was administered. And he says he "would have been concerned even in those days".

Other experts say Dr Milner should have published research if he was using treatment on young patients that wasn't being widely used elsewhere. We weren't able to find any.

It wasn't just the use of the drug itself that was questionable, but what Dr Milner is alleged to have done when patients were under its influence.

Marianne says she had an internal examination in the room, which was embarrassing and unnecessary, and other patients have alleged sexual abuse by Dr Milner.

'Marianne' recorded her memories of Aston Hall later in writing

Dr Milner died in 1975, making it impossible to put these allegations to him. However, his family point to another former patient who says she was treated with sodium amytal by Dr Milner after seeking his help voluntarily in the 1950s. She describes him as "wonderful" and says the treatment had made her life worth living.

Whatever the truth of these allegations, nearly all the patients we spoke to agreed Dr Milner asked very personal sexual questions during treatment.

"He asked me who'd interfered with me, and I went: 'Nobody'. And he said: 'Somebody's interfered with you'."

She remembers a young friend at the hospital having a similar experience, and asking Marianne to tell Dr Milner "my dad didn't abuse me".

"For her to have said that about her dad, I think it really hurt her, but I can understand it because he coerced you into thinking these things."

Some experts believe Dr Milner was trying to help his young patients talk about a sexual trauma they had either repressed or were uncomfortable talking about when fully conscious.

But because patients under the influence of sodium amytal are semi-conscious, in a highly suggestible state, there is a danger that asking leading questions can make them believe something happened that, in fact, didn't.

In the 1980s and 90s, the drug was at the centre of a number of law suits of so-called false memory, where patients mistakenly believed they had been the victims of abuse. In one notorious case, an executive from California sued a psychotherapist and was awarded half a million dollars after his daughter accused him of sexually abusing her following therapy. Sodium amytal had been used as part of the treatment.

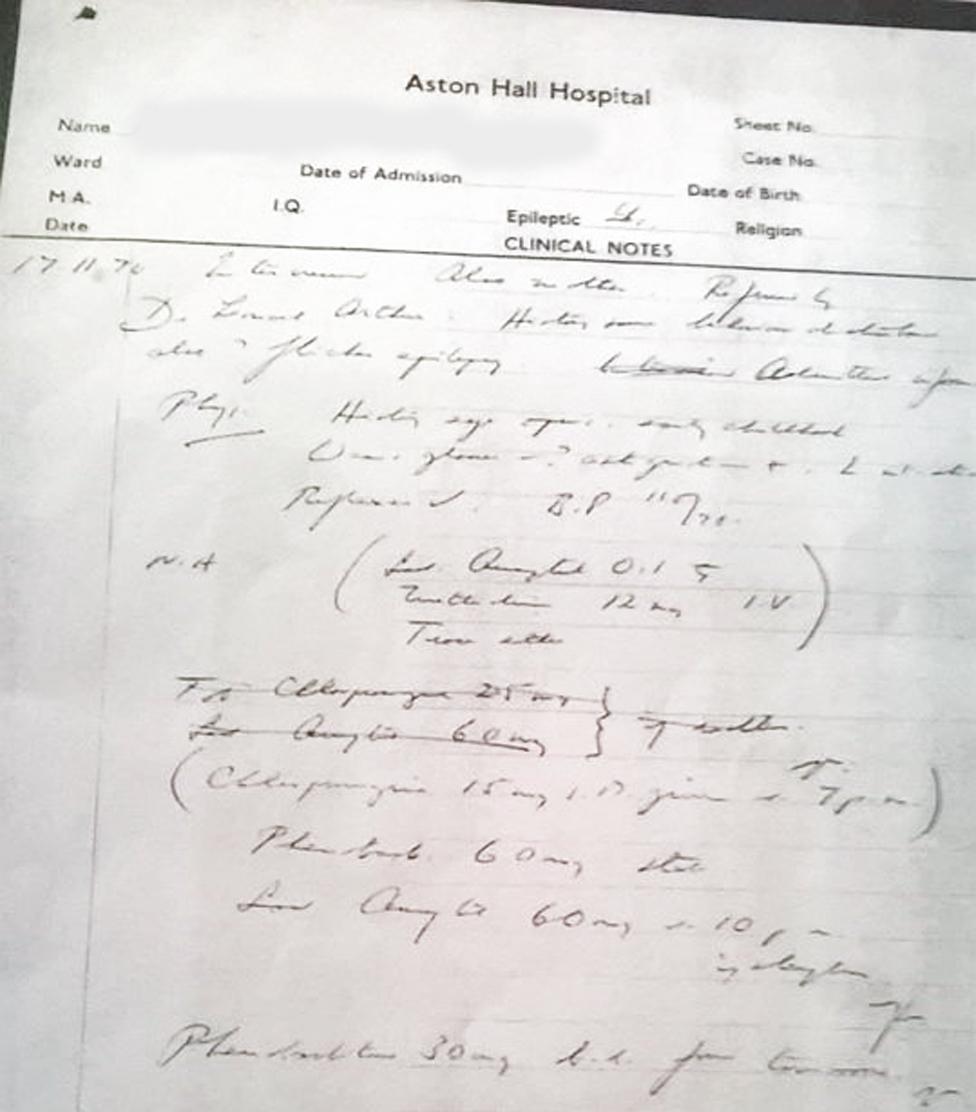

The medical records of a patient at Aston Hall (name blanked out) show the prescription of sodium amytal

"It is not a truth serum," says Prof Elizabeth Loftus, an expert in memory from the University of California, Irvine. "When it comes to the recovery of pristine, accurate, allegedly repressed memories, it's a danger."

Another former patient of Aston Hall, Sandra, thinks she may have been encouraged to develop false memories.

After nine or 10 sessions at the hospital, Dr Milner told her: "We've got to the bottom of it, you were a hard nut to crack!"

During treatment, he said, she had revealed her father had sexually abused her as a child. This floored her. "I was just so upset, totally devastated."

Parts of Aston Hall are now being redeveloped

Sandra's sister thought words had been put into her mouth. But she disagreed.

"You believe what the doctor says don't you?" she explains.

The accusation caused a rift with her family. Her sisters doubted it could have happened as they looked after her when she was little and say she was never alone with her father.

Eventually, though, Sandra changed her mind.

"It came to me, that perhaps this only did happen under treatment, and for 51 years I have been accusing my father of maybe doing something he did not do. And the worst part about it, if it didn't happen, I've got to live the rest of my life knowing that I've told people that he's done this. And accused him of doing it."

The authorities are now investigating what happened at Aston Hall Hospital. A police inquiry has been launched and the Derbyshire Safeguarding Children Board, a multi-agency body including police, health and social services, says it is working to ensure the allegations are thoroughly investigated and the appropriate support is in place for people who need it.

While former patients search for answers about what really happened to them, they may have to live with the harmful effects of the treatment for the rest of their lives.

If there is a story you would like File on 4 to investigate then please email fileon4@bbc.co.uk

File on 4: What happened at Aston Hall Hospital is on BBC Radio 4, 19 July at 20:00 BST - catch up on BBC iPlayer Radio

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external