The man with no-one to mourn him

- Published

Stewart Cooney, a 95-year-old war veteran, outlived his wife and son

He was set for a "lonely funeral" attended only by a carer and a social worker

An appeal to give him a good send-off was made on Facebook and in a local paper

When Stewart Cooney died at a nursing home in Leeds, only a handful of carers and a social worker took notice. But Dougie Eastwood, a trainer for the care service running Stewart's nursing home, was upset to think he would not be mourned.

"We're in the world for such a short time, no-one deserves to go to the grave without being recognised," he says.

"I asked one of the nurses about Stewart and she told me he had been in World War Two. He was in the Royal Artillery and served in Egypt and Sicily. It didn't feel right someone who served his country should pass by unnoticed."

Cooney, described by carers as "lovely" and "cheeky", was 95 when he died. His wife Betty passed away in 2008 and the couple's adopted son died in 2014.

"He would talk about his wife a lot, he called her Barnsley Betty, as that was where she was from," says Janine, a carer who worked with Cooney from 2012 to 2014.

"He had dementia so he would sometimes get a little confused and think he had been out doing things with them.

"He was always pleasant and loved to sing. He would sing whole Frank Sinatra songs and get us to join in."

He was moved to a nursing home in March this year, and died three months later.

Who was Stewart Cooney?

Born in Dundee in 1921, he trained to be a jute weaver, external at 16

Enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1943 and fought in Egypt and Sicily, before taking part in the Battle of Monte Cassino, external in 1944

Married Betty, a telephonist in the Royal Artillery, at Dalmeny Church in Midlothian in 1944

Adopted a son, Niall, in 1953

Worked as a loom tuner (looking after weaving machines) at a mill in Farsley, near Leeds

Died at Colton Lodges Nursing Home in June 2016

According to the National Association of Funeral Directors, only a tiny proportion of funerals - no more than 1% - are attended by no family or friends.

"However, there are occasions when someone dies without family or friends to mourn them", says the NAFD's Deborah Smith. "The funeral director will often attend in these instances, together with someone such as a social worker or carer."

Funeral celebrant Lynda Gomersall thinks the number of such services is rising on account of Britain's rapidly ageing population.

"Funeral directors I work with say they are becoming more common because people are living longer and are outliving their families," she says.

"It also becomes harder to track down friends and relatives if the person suffers from dementia later in life."

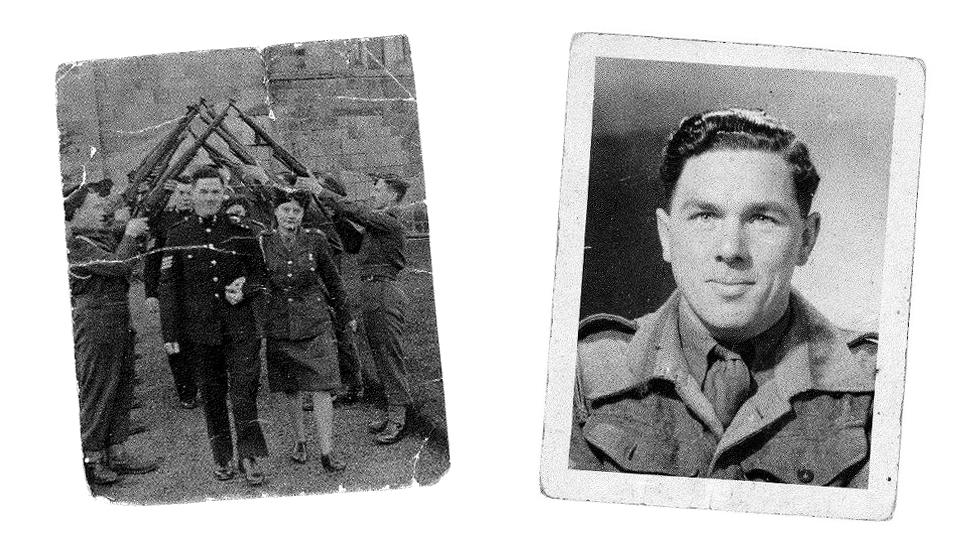

Stewart Cooney on his wedding day and in uniform

Dr Rebecca Nowland, from Bolton University, who has studied the impact of loneliness in Britain, notes that older people "can get forgotten".

"I think this is partly due to our modern lifestyle. We are so busy now and don't have the cross-generational connections we used to have," she says.

She thinks the reason people feel deeply uncomfortable about the idea of a "lonely funeral" is because - rightly or wrongly - we often judge our own worth by our value to others.

"As a social species recognition by others is important to us: it is something we seek out and crave. We value other people's opinions of us greatly as it helps us to feel connected to others. In addition, the absence of this or the rejection by other people is a very uncomfortable state to be in."

This helps explain the coda to Stewart Cooney's story.

Stewart Cooney fought at the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944

Dougie Eastwood got in touch with the 269 Royal Artillery battery, who researched his military background and put a call-out for people to attend his service. Eastwood also spoke to the local newspaper , externaland appealed for people to attend via social media. He was amazed by the response, with 40 phone calls offering support from flowers to military escorts.

"I'm humbled by how the army family and local community have come together," he says.

One of Stewart's former carers Janine, decided to go after finding out about the funeral on Facebook.

"I think he would have really liked it, especially with the military people coming," she says.

"He would have liked to have chatted with them - he was so proud of his time in the army."

The crematorium was full today

Lynda Gomersall offered her services after seeing the appeal on Facebook. She spoke to Cooney's carers and looked through old records to write the eulogy.

"I don't think anybody should go without recognition, especially soldiers," she says.

Originally around three people were expected at Stewart Cooney's funeral. Instead, more than 200 turned up and those who didn't fit in the crematorium watched on screens outside.

The coffin was piped into the crematorium by a Scottish piper, in homage to Cooney's Scottish roots. Soldiers from a number of regiments were present and the Last Post was played.

"There were at least nine standards and three buglers who were in their thick red ceremonial uniforms with pointed helmets. Four Territorial Army soldiers flanked the coffin," Gomersall says.

"Some long lost relatives even turned up including his sister."

The coffin left the crematorium to Frank Sinatra's My Way and was placed in the hearse alongside a floral wreath depicting his army number. The cortege to Pudsey Cemetery in West Yorkshire included 66 motorbikes from the Royal British Legion Riders.

"It was a wonderful day. I hope we did Stewart proud."

Find out more

Follow Claire Bates on Twitter @batesybates, external

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external