The global philosopher: Who should pay for climate change?

- Published

A global audience joins Michael Sandel to discuss who should foot the bill

Most climate scientists think the world is getting warmer and that humans are at least in part responsible. Almost every country in the world has pledged to make efforts to stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere in order to prevent dangerous "interference with the climate system". But exactly how to do this raises interesting questions about fairness.

To discuss them, we put Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel in a state-of-the-art digital studio - connected to 60 people in 30 countries. Here producer David Edmonds outlines three key puzzles.

Who is responsible?

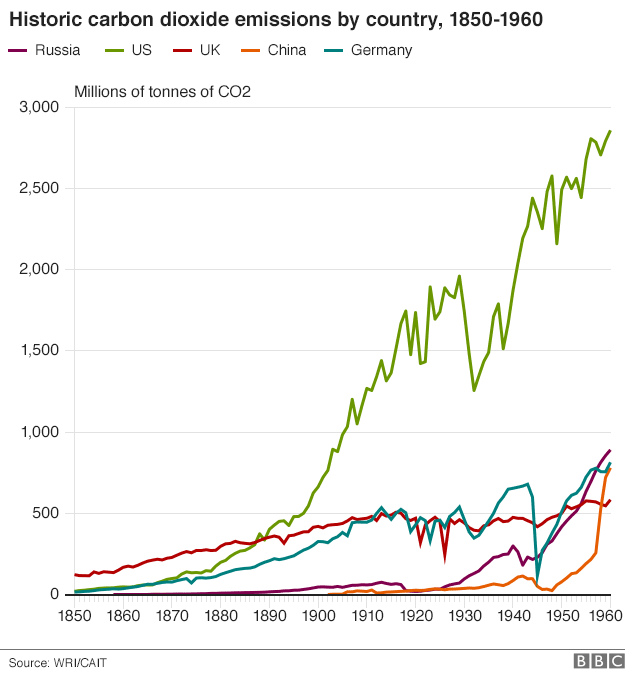

We have been pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere in ever increasing quantities since the industrial revolution. Some countries in the developed world are, of course, responsible for the bulk of this. Since 1850 the US and the nations which are now the EU have been responsible for more than 50% of the world's carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

So shouldn't they pay to fix the problem? The inhabitants of The Maldives - made up of more than 1,200 islands, most of which are no more than one metre above sea level - are already feeling the effects of climate change. They are victims. But they didn't cause the problem. Should those countries with historical responsibility for emissions be obliged to compensate The Maldives?

The old industrialised world might respond that for much of the period since the 1850s nobody knew about man-made global warming. Does that mitigate its responsibility? And why should the current generation be punished for the crimes of its forebears? Is that really fair?

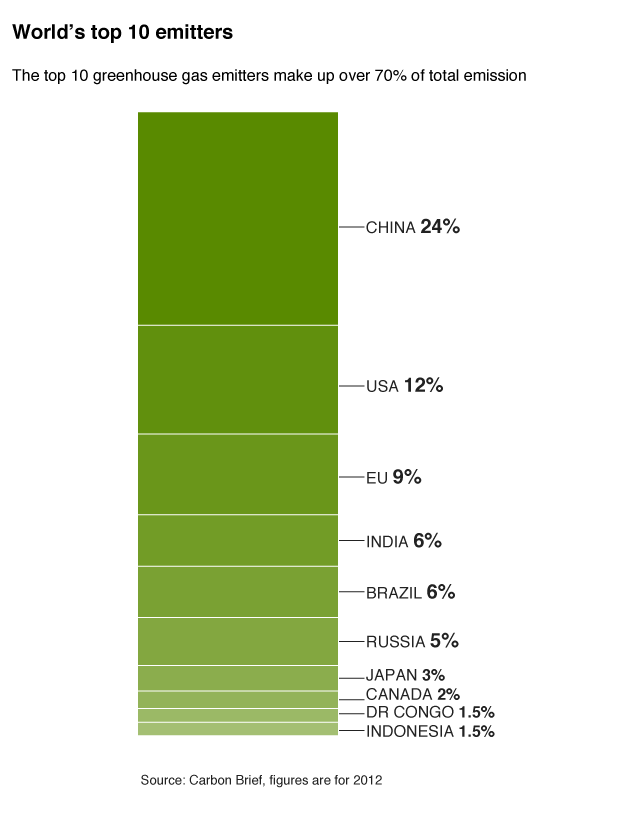

Then there's the question of who's polluting now - when we do know the damage it's doing. China belts out more CO2 than the United States, and the gap between the two is expected to grow as China continues to develop. So perhaps it is China, not the United States, which should bear the greatest burden?

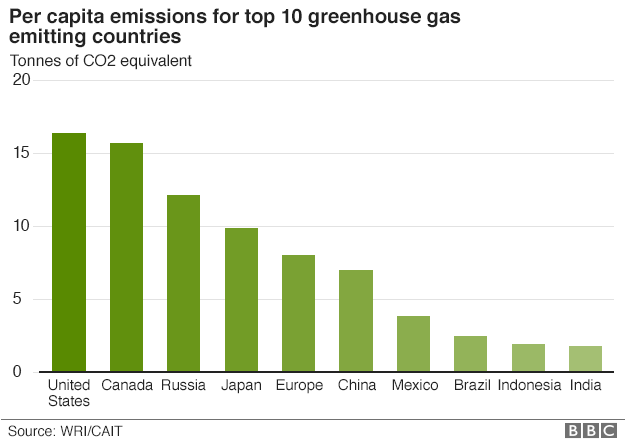

Or, yet another possibility, surely the fairest solution would be a per capita arrangement? China now emits more than the US because its population is four times the size. But on average, each Chinese citizen is much poorer than each American, and with a much smaller environmental footprint.

These are the sorts of questions which have dogged global climate change summits. And you can see why.

Is carbon trading a good idea?

One brilliantly innovative way to deal with global warming emissions is carbon trading. Here, broadly, is the idea. Countries (or states, or companies), are given an allowance to emit a certain amount of the gases that cause climate change - CO2 for example. If a country wants to go beyond its allowance, it can buy the right to emit from other countries, which will compensate by cutting their emissions. If this market-based system works as it's supposed to, it's an efficient and cost-effective way of cutting overall emissions. Emissions can be trimmed in countries where it's cheap to do so, rather than in countries where it's expensive and difficult.

But even if the market is effective, is its use appropriate? Some have compared carbon trading to the Roman Catholic medieval practice of allowing individuals to pay money to reduce punishment for a sin. A tongue-in-cheek website - cheatneutral.com - allows people who are sexually unfaithful to their partners to "offset" their cheating by "finding someone else to be faithful and NOT cheat". Is that really what we're doing when we trade carbon? If it works, does it matter?

Is carbon trading like a website that offers people the chance to offset infidelity?

Should we consume less anyway?

Technology is advancing at breakneck speed. Suppose there were technological fixes for climate change and ecological damage. In other words, suppose that we didn't need to worry about how much we consumed. In this future world, we can carry on munching and guzzling and buying more and more at no environmental cost. We can fly more, watch bigger televisions, generally own more stuff. Would this be an unqualified good?

To some this would be a utopia. To others, and they include Pope Francis, it would not. What's required, he wrote in a recent encyclical, is a complete revolution in our attitude towards the environment. We shouldn't regard the environment as of mere instrumental value. We should consider it with awe and wonder. "If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder… our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on [our] immediate needs."

If the Pope's right, then a scientific answer to climate change might, in one way, be a cause of regret. It would deprive us of the incentive to change our mindset, to readjust our relationship to the countryside and wildlife.

Find out more

The Global Philosopher: Should the rich world pay for climate change? is on Radio 4 at 09:00 on Thursday 28 July. You can listen later online or watch the debate here.

These three issues hardly exhaust the philosophy of climate change and the environment. There are all sorts of other issues. We might ask ourselves whether, as individuals, we have any responsibility for the future, since the impact any one of us can have is negligible. We might wonder whether our obligation to people yet unborn is less important than our obligation to those already alive.

These are all tough questions, questions which are essentially philosophical in nature. But they're also questions we need to address, discuss and resolve, if we're to deal with climate change and its consequences. Step forward, the Global Philosopher…

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external