Firing at stone-throwers in Indian-administered Kashmir

- Published

Over the last month in Kashmir some 60 people have been killed and more than 5,000 injured in an upsurge of violence. It is a major setback for peace in the troubled region, which is claimed by both India and Pakistan.

"This is the bullet that killed my son," Abdul Rehman Mir says, holding up a copper cartridge case.

He tells me the police raided the family home in Srinagar, the capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, a month ago.

They smashed windows and fired tear gas grenades. He's kept what's left of the grenades too, wrapped in a handkerchief stained with his son's blood.

"They dragged him from here," he tells me - we're in one of the rooms on the first floor - "and they shot him in the garden. That is where he died."

There is a ripple of anger from the crowd that has followed us into the house.

The state government denies this allegation. It says Shabir Ahmad Mir was killed as the police tried to control a crowd of stone-throwing youths.

As I talk to Mr Mir I hear the low rumble of voices outside. Then the chanting begins.

A crowd gathers in Srinagar, Kashmir, calling for freedom from India

Word has spread that the BBC is here and more people have gathered, defying the curfew that bans anyone from going outside in sensitive areas like this during daytime.

"Azadi! azadi!" - freedom, freedom - they cry.

I'll be honest: I'm afraid. I am in a house surrounded by an angry crowd down a maze of alleyways in a city kept in lockdown by the police and army.

But their fury is all directed at India.

"Go India, go back!" they chant.

Muslim-majority Kashmir became part of India when the British pulled out in 1947, and a substantial portion of the population has been demanding independence ever since.

When we go downstairs, the chanters are respectful. They want to tell me about what has been happening, and ask why the unrest here doesn't get more attention from the world media.

It's true that troubles in Kashmir were once a big story. If you were looking for a flashpoint that could spark a major international conflict, this was it.

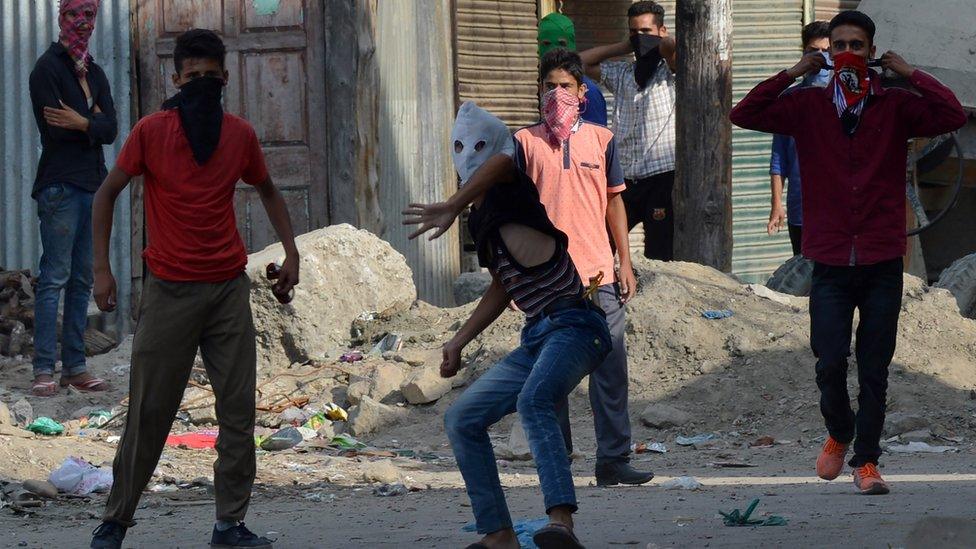

There have been violent protests from disaffected young Indian Kashmiris

The lush green valleys of the region are claimed by India and Pakistan - both nuclear powers. They have fought two wars over Kashmir, and it remains one of the most militarised regions in the world.

The dangers of escalation haven't gone away, it's just that other issues have eclipsed Kashmir - 9/11 and the wars that followed it, the rise of IS, the conflict in Syria, terrorism in America and Europe.

The recent upsurge in violence here was triggered by the killing of a charismatic young militant, Burhan Muzaffar Wani. The 22-year-old had built up a huge social media following among disaffected young Indian Kashmiris.

"Burhan," as he is universally known in Kashmir, was killed in a shoot-out with police on 8 July.

There's disagreement about whether the Indian authorities deliberately targeted him, but once Burhan was dead they certainly knew what was coming. The mobile phone network was shut down; the curfew was imposed; reinforcements were rushed in.

And more than a month later, India is still struggling to contain the violence.

I watch as a young man, two ragged eyeholes in the scarf that covers his face, darts out and hurls a stone towards the lines of police. As it arcs out of the evening sky I get ready to run for cover, but a policeman deflects it deftly with his riot shield.

Another draws out a powerful catapult and fires a stone back.

"It is to keep the crowds away from us," the commander, Rajesh Yadav, says by way of reassurance.

And as well as the catapults and their rifles his men have tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and - most controversially of all - shotguns.

"We use the 9mm pellets to minimise injuries. My men have to be able to fight back," says commander Yadav.

But whatever size the shot, it does real damage.

In the main hospital, there is an entire ward full of young men in sunglasses, which often shield horrific wounds.

"The tiny pellets ricochet around the soft tissue," a doctor tells me. "Dozens will lose their sight."

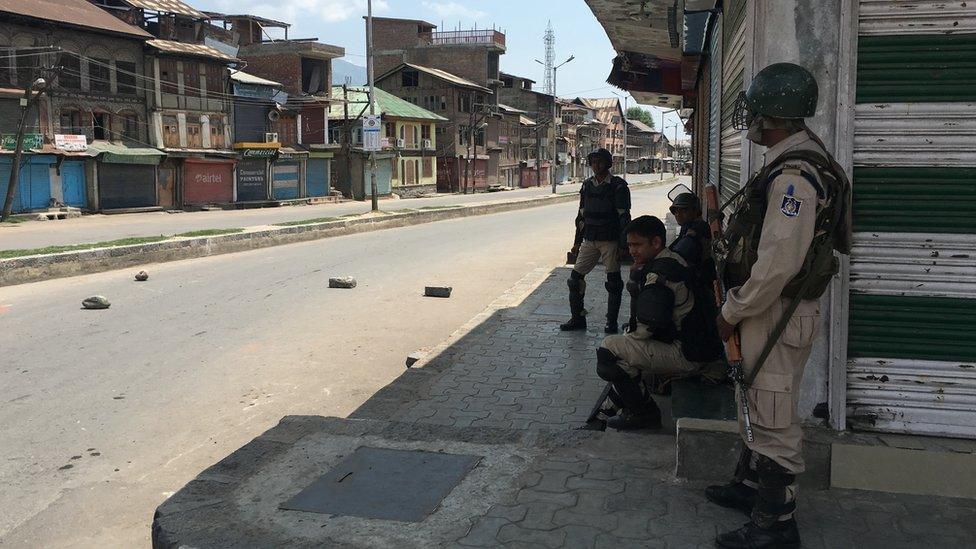

An Indian paramilitary officer aims a sling shot towards Kashmiri protestors during a clash in downtown Srinagar

It is hard not to see India's brutal approach to crowd control as adding to the spiral of violence, but it doesn't have many other choices.

It has already devolved considerable powers to Kashmir, and refuses to talk to hardline separatists. Meanwhile, it is adamant that independence is not on the cards. So its approach is to pour in yet more police and troops, hoping to hold the line until the protests die away.

It has worked before - but it is risky.

As night falls, the last of the youths slips away into the darkness, but this scene will be repeated tomorrow and in the days that follow.

"Every mother will give birth to a Burhan," mutters one of the policemen, as he trudges wearily back to his HQ.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external