Rio 2016: Does John Major deserve credit for Team GB's success?

- Published

John Major (centre) pictured with Seb Coe (right) at the London 2012 Velodrome

The sight of Team GB above China in the Olympic medal table has led some to heap praise on John Major, whose government took the decision to launch the National Lottery. The lottery has poured money into sport in the UK, but can it claim credit for medal success?

When Adam Peaty powered to the finish line in his record-breaking 100m breaststroke, it was the result of a big investment by UK Sport.

Although spotted as a potential star at the age of 14, Peaty at first relied on fund-raising parties, organised by friends and neighbours, to pay for his travel to national competitions.

Then in 2012 he was awarded a grant of £15,000, while his coach got a place on an elite coaching programme. Both were funded by UK Sport, which receives two-thirds of its funding from the National Lottery. All direct payments to athletes are entirely lottery-funded.

Two years later Peaty beat the then Olympic champion in the 100m breaststroke final at the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow - the first of many international titles.

Top athletes with a record like this are eligible for an annual grant of up to £28,000, leaving them free to concentrate on training.

In addition to funding athletes directly, UK Sport gives money to the governing bodies of selected sports - such as British Swimming - to spend on training facilities and trainers, such as Adam Peaty's coach, Mel Marshall.

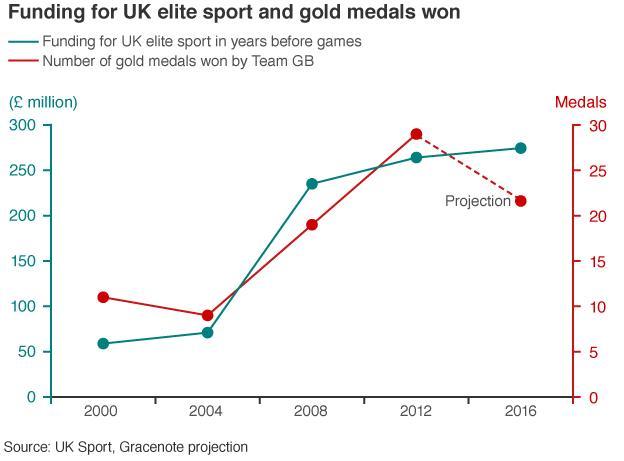

Reportedly, the UK government spent just £5m per year funding Olympic sport before the 1996 Atlanta games. But UK Sport spent £54m on elite sports in the run-up to the Sydney games in 2000 - where Team GB won 28 medals and ranked 10th. By the time of London 2012 it was spending £264m, and Team GB came third in the medal table, with 65 medals.

Is that convincing evidence that money buys medals?

"Perhaps the strongest evidence is to compare the results Team GB are achieving now and compare them to Atlanta 1996 - the last games before National Lottery funding was introduced when we won one gold medal and came 36th in the medal table," says a UK Sport spokesperson.

Experts appear to agree.

"As a researcher I guess I will always have to say that 'correlation does not mean causality'," says Prof Borja Garcia from Loughborough University. "So it cannot all be put down to the increased funding. But it is undeniable that the increase in funding has produced better overall results at the (summer) Olympics."

However, Garcia notes that the way money is spent is also critical.

"It's not so much the amount of money but the way in which it has been targeted, invested and audited," he says. "It has certainly produced results even if some people think of it as a somewhat 'brutal' approach."

It's brutal in that funding is only awarded to sports that succeed in demonstrating medal potential in the next two Olympics - and one poor Olympic result can lead to funding being cut altogether.

Which sports are funded?

Before the beginning of each funding cycle, all sports present to UK Sport a detailed, costed strategy and agree a range of medals which they will aim to achieve at the following Olympic or Paralympic Games.

UK Sport scrutinises all the strategies and allocates funding on a "top-down basis". As a spokesperson puts it: "We start with the sports which are targeting the most medals and work downwards i.e. we do not 'salami slice' funding and give some to every sport." The level of funding in each sport is assessed annually and benchmarked against results at milestone target events in each year, to determine whether they are on track for the next Games.

Chair of UK Sport, Rod Carr, defended the tough strategy on BBC Radio 4's Today Programme, pointing to the example of British Gymnastics: "In the early 2000s they were in a pretty low state. They hadn't had a good Games at Sydney and their funding was cut as a result of that. They went right back to basics, they disassembled their programme and looked at what was working and what wasn't and then built it up again."

The women's indoor volleyball team rose more than 60 places in the rankings to reach the world's top 20 in the four years prior to London 2012 - but all funding was withdrawn when they did not win a medal. The UK did not even send a volleyball team to Rio this year.

On the other hand, sports that do well - such as cycling and rowing - continue to receive funding, which helps them to stay at the top.

Money paid directly to athletes by UK Sport all comes from the National Lottery

Liverpool University economist Prof David Forrest agrees that increased funding has delivered more medals, however, he warns that funding for elite sport may not remain at its current level.

"Generally we see an increase in medals in the games before a country hosts it, a further increase at their own games and a bump in medals in the two games afterwards," he says.

"After this results tail back to average. This could well be because politicians are more reluctant to spend extravagantly on elite sports. Priorities may shift."

This could mean less money being spent on sport - or perhaps a re-balancing of the money spent on elite sport, on the one hand, and community sport on the other.

The Department for Culture and Media and Sport reduced spending on community-level sport by 5% for 2015 and 2016, while protecting elite sports to guarantee, external "an Olympic sporting legacy."

But if funding is cut at the grass roots this does eventually affect the top of the tree, Forrest says.

"In the long term, selectors will find they have a far smaller pool of athletes to choose from when choosing athletes for development programmes."

Overall, 25% of the money from National Lottery ticket sales is spent on good causes, and 20% of that is allocated to sport. Some of that goes to UK Sport, which funds elite sport, and some goes to the home nation sport councils - Sport England, sportscotland, Sport Wales and Sport NI - which fund community sport.

Many British athletes at the Rio Olympics have effusively thanked the National Lottery in televised interviews after winning a medal.

"I knew there was no chance of funding the long-term development of sports and the arts from general government revenue," John Major told the New Statesman in 1999. "A lottery could do just that."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external