My friend the North Korean defector

- Published

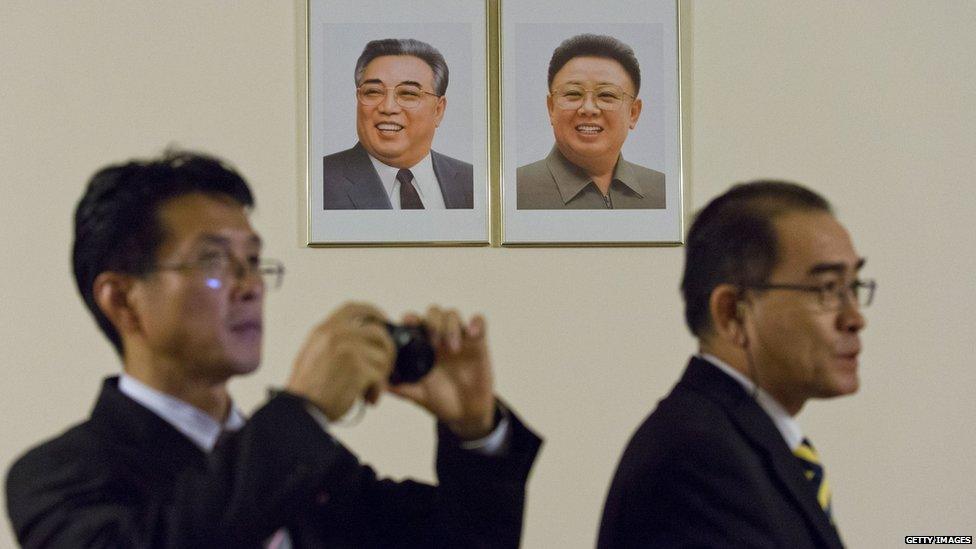

Mr Thae (right) is not answering emails

It was reported on Tuesday that a North Korean diplomat in London, Thae Yong Ho, had defected to a third country. The BBC's Korea correspondent, Steve Evans, has pleasant memories of Mr Thae - who, he says, always seemed unusually at home in the suburbs of West London.

The last time I saw Thae Yong Ho was in an Indian restaurant in Acton, in West London. He was eating a curry, but without rice - we had been discussing pre-diabetes, a condition which middle-aged men who enjoy food come to think about a lot, usually at the suggestion of their doctors.

His GP had told him that he should think of diabetes as a monster running towards him. He could slow it down or he could speed it up, but towards him it was coming. Rice and other carbohydrates would bring the monster closer faster.

Now the curries will have to be elsewhere - in Seoul, with a bit of luck. He is here with his family after disappearing from London. His stint as a diplomat for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, as he called North Korea, came to an end earlier in the summer and he told me he was returning with his family to Pyongyang.

But he wasn't. He is a dark horse - but of course he had to be. He worked for a regime which has a history of abducting people and the least hint of defection would have landed him in deep trouble.

Thinking about it though, the signs were there. I recall he asked me about life in Seoul. I told him it was a mega-bustling city, a world away from Pyongyang .

But he seemed so British. He seemed so at home. He seemed so middle-class, so conservative, so dapper. He would have fitted in nicely in suburbia.

In fact, he did fit in nicely in suburbia. He told me how he had been passing the local tennis club in Ealing and had seen a sign asking for new members. In he went and joined, and became a stalwart of the tennis club.

He took to tennis when his wife complained about his obsession with golf. There must be a million conversations like it in the shires - his wife told him it was either golf or her. If he didn't put down the putter, she was off to Pyongyang.

For North Koreans, as for everyone else, love (often) conquers all. So he put down the golf bag and took up the tennis racket which - the tennis club being closer - left him more time for home.

North Korea's London embassy is located in Ealing, west London, where Mr Thae was also a member of the local tennis club

We often talked of family - and health. The children of North Korean diplomats in Britain go to local state schools. They sometimes note how their children's first words of English are "Stop doing that!" or "Enough!" - echoing the teachers of Acton.

Mr Thae's son had a degree in the economics of public health from a British university. His son had concluded from his studies that what Pyongyang really needed to make it a world-class city was more disabled parking spaces.

I'm no expert in these things but I am sceptical. Of all the things Pyongyang needs, more parking space for the disabled is not top of the list. More cars, maybe. More freedom, certainly. Disabled parking can come later. That is my opinion.

Mr Thae had done his duty, going round Britain promoting the country's ideology. He gave a talk to the Revolutionary Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist) where he bemoaned British house prices. He would tell his friends how much he paid to rent a house in Acton and they assumed it must be a mansion with a swimming pool rather than a small semi. Despite that, he has chosen not to have the free accommodation he cited as one of the benefits of life in Pyongyang.

I am pleased at his decision. Who knows how much agony there must have been wrestling with the choice. When I met him, it was always with another diplomat present - that's the way Pyongyang keeps control - one diplomat watches the other for disloyalty.

He had never given any hint of disloyalty to the regime, not a flicker of doubt. But when you talk to North Korean officials you know where the red lines are.

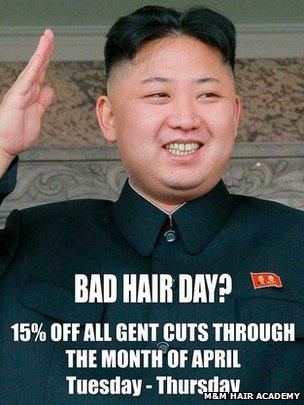

Two diplomats complained when an Ealing hair salon put Kim Jong-un on an ad

In Pyongyang there are the hardliners from the security agency - hatchet-faced men with bulges under their identical suits - but there are also the minders from the foreign ministry, with whom human engagement is possible. They can be helpful, though never disloyal to the regime. It is more than their jobs are worth - more than their lives are worth.

And so it was with Mr Thae - helpful within the constraints of his job. I should say that while there is no doubt fear in the minds of public officials there is also, I think, genuine patriotism and even pride in the country.

Mr Thae must have done a lot of dirty work, despite showing such a charming face to me in the curry house in Acton. Was he one of the two men who turned up at the barber's shop in London to complain about the picture of Kim Jong-un with the caption, "Bad hair day?"

Did he follow North Korean defectors in the Korean enclave in New Malden in South London? I don't know, but it was part of the job as a representative of Pyongyang's despotism.

He was one of the minders escorting Kim Jong-un's brother to an Eric Clapton concert in the Albert Hall - he is the balding man seen in the first few seconds of this video:

This footage appears to show Kim Jong-chul (L) at the Royal Albert Hall in London

According to the South Korean media, the diplomat has defected because of pressure from Pyongyang to counter bad publicity. In this regard the BBC - to its great credit - may be to blame. On our last trip to North Korea, BBC reports upset the regime greatly. My colleague, Rupert Wingfield-Hayes, was banned from the country for life and was lucky not to get hard labour.

I can imagine the phone calls: "How could you let this happen?" "Why did you trust the capitalist lackeys?" They had already said the opening of the BBC's new Korean Service would be viewed as an act of war.

If you were Mr Thae, what would you do? Get on the plane to Pyongyang to get more abuse and perhaps even severe punishment, or seek asylum with your family in the UK, or perhaps the US?

I do not know - but there's got to be a spy novel or a movie in it. Despite the skulduggery which Mr Thae may have been involved in, I like him. It should be a movie with a happy ending, perhaps with Mr Thae playing tennis in his later years, perhaps on the hard courts of South Korea.

Better still on the gentle grass of Britain.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external