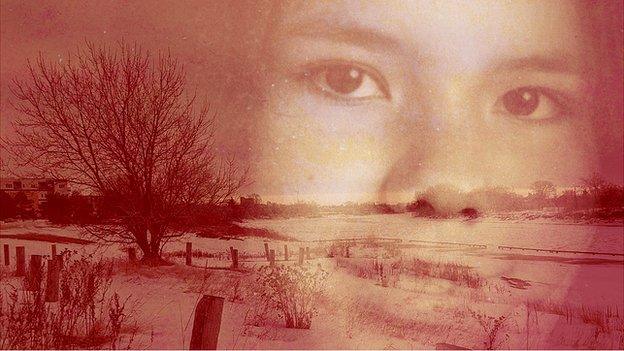

The town where 100 young people have tried to kill themselves

- Published

When Justin Trudeau came to power in Canada, he promised to repair the country's relationship with its aboriginal people, after centuries of discrimination. A disproportionate number of indigenous women have gone missing or been murdered in recent decades, and suicide attempts have risen dramatically in some communities, writes Stephen Sackur.

Attawapiskat is hard to reach. Generations of Canadian politicians have never lent it a thought, still less a visit. But this ramshackle aboriginal settlement south of Hudson Bay has been making national news over the past year for the grimmest of reasons.

Last October a 13-year-old girl, Sheridan Hookimaw, headed to the rubbish dump and hanged herself. Since then more than 100 of Attawapiskat's 2,000 First Nation people, most of them teenagers, but one just 11 years old, have attempted suicide.

Jackie Hookimaw, a Cree native of Attawapiskat, a teacher, and Sheridan's aunt offers to show me around.

We set off down a dirt track past wooden cabins with boats and tepees in the backyard. A teenage boy is loading containers on to a quad bike outside a shed.

"That's the water treatment plant," says Jackie. "It's the only place to get drinking water. The stuff that comes out of the tap is so toxic folks won't shower in it, let alone drink it. We get everything here from rashes to cancers."

The track takes us to a sports hall. There's a makeshift gym, dumbbells, a couple of weight machines and a fug of stale sweat.

I meet 19-year-old Skylar Hookimaw, his brow furrowed, biceps straining. Sheridan was his little sister. "It still doesn't feel real, like it didn't happen, but it did," he sighs.

There's a heavy silence. "Why is it happening so often?" I ask.

"Family problems, bullying, drugs, alcohol," says Skylar. "Kids feel like they've been left alone, like they don't matter."

Find out more

Watch Hardtalk on the road in Canada on BBC World News or catch up later online

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Back in April, 11 youngsters tried to kill themselves over the course of one weekend. The day before I arrived, a teenage girl slashed her wrists and had to be airlifted out. The week before, an "at risk" boy tried to hang himself.

Jackie takes me out on a canoe on the Attawapiskat River. Her people have fished here, hunted goose and caribou, for countless generations. We glide past four girls playing in the water, diving, splashing, shrieking with laughter.

"You wouldn't know it, but those girls are struggling," says Jackie as she waves a greeting. "Our young people are lost. They don't feel valued. They feel disconnected from their culture and they need help."

Justin Trudeau at a smudging ceremony during the National Aboriginal Day Sunrise Ceremony in Gatineau in June

Help, claims Justin Trudeau, Canada's youthful premier, is on its way. He's promised a fresh start in Canada's relationship with its 1.4 million aboriginal citizens. He pledged more money for their communities, a new focus on education and mental health in First Nation reserves like Attawapiskat.

He's also launched an inquiry into another dark aspect of the indigenous experience in modern Canada - the shockingly disproportionate levels of violence directed against First Nation women. In the past 30 years more than 4,000 indigenous women have gone missing or been murdered.

Many of them fall through the cracks when they get to Canada's cities. The police, the courts, social services all have a shameful record of failure - failure to protect, to investigate, to prosecute and ultimately to care.

In prosperous Calgary, a western city grown rich on cattle and oil, I join a rain-soaked vigil to mark the death of 25-year-old Joey English. Her dismembered body was found in a city park in June.

A couple of dozen friends join Stephanie and Patsy, Joey's mother and grandmother as they sing and drum and remember. "It's like when you cut yourself and you can't control the flow of the blood, that's how I feel," says Stephanie. When Joey's grandmother speaks, the anger is raw. "I'm so pissed off with the justice system," she says. "I'm so tired of this. Our families, our sisters need help."

Beyond the small circle of mourners, Calgary's streets are packed with revellers in the city for the annual Stampede - it's all Stetsons and cowboy boots and a celebration of Canada's Old West - the pioneers who settled a vast empty land. Except it wasn't empty. It was the land of the Blackfoot, the Kainai, the Cree and so many more.

"We were taught to be silent," says Sandra Manyfeathers, whose sister, Jacky Crazybull, was murdered during the Calgary Stampede nine years ago. "But we're saying you're not gonna kick us, you're not gonna keep us down. No way are we gonna be quiet any more."

If you are affected by this issue

The Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention maintains a page of crisis centres in Canada, external

In the UK, the Samaritans, external maintains a hotline for anybody who needs to talk

Red River Women

Each year, dozens of Canadian aboriginal women are murdered or disappear never to be seen again. Some end up in a river that runs through the heart of Winnipeg. One of them was a 15-year-old school girl called Tina Fontaine, whose body was found in August 2014.

Read about Canada's Red River Women.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external