Paolo Macchiarini: A surgeon’s downfall

- Published

Ground-breaking work on synthetic organ transplants made Paolo Macchiarini one of the most famous doctors in the world. But some of his academic research is now seen as misleading, and most of the patients who received his revolutionary treatment have died. What went wrong?

In July 2011, the world was told about a sensational medical breakthrough that had taken place in Stockholm, Sweden. The Italian surgeon Paolo Macchiarini had performed the world's first synthetic organ transplant, replacing a patient's trachea, or windpipe, with a plastic tube.

The operation promised to reshape organ transplantation. No longer would patients have to wait for a donor organ, only to run the risk of biological rejection. Plastic tracheas - and possibly other organs - would be produced quickly, safely, and made-to-measure for each patient.

It was a story that befitted the reputation of Dr Macchiarini's workplace, the prestigious Karolinska Institute, whose professors decide each year who will receive the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

But five years on, Macchiarini's headline-making work has brought KI and its sister organisation, the Karolinska University Hospital, no glory. Of the nine patients that received the treatment, in Sweden and elsewhere, seven have died. The two still alive have had their synthetic tracheas removed and replaced with a windpipe from a donor.

Last week, an independent report, external sharply criticised the three synthetic trachea operations that took place at Karolinska University Hospital.

The investigation, led by Kjell Asplund, Chairman of the Swedish Council on Medical Ethics, found that the scientific foundation for the new operation was weak, and condemned the failure to carry out risk analyses before the patients received their operations, or seek the necessary ethical approval.

On Monday, a separate investigation, external at KI identified mistakes made when Macchiarini was recruited and when allegations of misconduct were made against him two years ago.

In the picture that emerges from these reports, we see a doctor persisting with a technique that showed few signs of working and able to take extraordinary risks with his patients, and a medical institution so attached to their star doctor that they ignore mounting evidence of his poor judgement.

Macchiarini arrived in Stockholm in 2010, already a leader in the field of regenerative medicine - the project of growing tissue or organs to be implanted in sick patients.

Not only was Macchiarini known as a brilliant surgeon, he was handsome and impressive - able to give press conferences in several languages.

At the hospital, a "bandwagon effect" emerged around his work. "Regenerative medicine" was at the cutting edge of scientific fashion, and few colleagues raised questions or objections about the basic science underlying the procedures.

The patient who received that first synthetic organ transplant, in 2011, was 36-year-old Andemariam Beyene, a graduate student from Eritrea living in Iceland. After unsuccessful treatment for a rare form of cancer, he had been referred by his Icelandic doctors to the experts at Karolinska University Hospital.

Macchiarini told Beyene that the revolutionary surgery was his only chance of survival and persuaded him to agree to the new procedure.

The synthetic "scaffold" for Beyene's new trachea was made in a lab in London. It was seeded with stem cells taken from the patient's bone marrow, then placed in a shoe-box sized machine called a bioreactor, where it rotated in a solution designed to encourage cell growth.

A synthetic trachea before being placed in a bioreactor

Stem cells being drizzled on to a synthetic trachea

The idea was that these cells would divide and turn into tracheal cells. Before the operation, Macchiarini also deposited slivers of cells from the patient's nose on the scaffold. It was hoped these would grow into a lining of epithelial cells. In effect, the doctors were trying to grow a new trachea inside Beyene's body.

A month after the operation, reporters from around the world were able to interview Beyene in bed. He told the BBC: "I was very scared, very scared about the operation. But it was live or die."

By the end of the year, Macchiarini and his colleagues were writing in the Lancet that Beyene had an "almost normal airway" that was free of infection and growing new tissue.

The publication of this sent a signal to the medical community that the miraculous-sounding project of growing and implanting synthetic transplants was a viable treatment.

By this time, two more synthetic tracheas had been implanted. In the first - an operation not overseen by Macchiarini - a young British woman in a serious condition received a trachea at University College London. In the second, Macchiarini himself fitted a 30-year-old American man with a new kind of scaffold.

These two patients only survived for a few months. No autopsy was performed on the American man so his exact cause of death is unknown, but we know that the British woman's synthetic trachea did not function well.

Andemariam Beyene met up with Paolo Macchiarini in Iceland in 2012, one year after his operation

"The biggest problem with the materials used at that time was lack of integration into the surrounding bodily tissue, both outside it and at the ends where you join it on to the bronchi and the larynx," says one of the surgeons, Prof Martin Birchall at UCL.

"At those junctions it always seems to be loose and healing tissue can become an obstruction to breathing.

"The second thing that seemed to happen was that you are putting the trachea on to a bed, which is made up of the oesophagus, the swallowing tube, and the synthetic material could press into the oesophagus.

"Finally, the lining didn't seem to grow into the scaffolds either, so you are left with something chronically infected and unable to clear mucus properly."

The patient was able to go home after the operation, but died two months later.

Over the next three years, Macchiarini implanted six more synthetic tracheas, and four of these patients died. It is unknown whether their deaths were all related to the tracheas, or whether they were due to underlying illnesses or even unrelated events.

Karolinska University Hospital stopped Macchiarini's work in November 2013, but he continued to perform the transplants as part of a clinical trial in Russia.

Meanwhile, reports about the health of the first patient, Andemariam Beyene, remained positive. In a 2014 article published in the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Macchiarini reported that he had an "almost normal" airway a year after the operation, repeating the phrase from the Lancet article.

But by the time that article appeared Beyene too had died. He had suffered repeated infections, and his trachea needed to be held open by a series of stents. His autopsy revealed the synthetic trachea had come loose.

The nine synthetic trachea patients

Source: SVT production team. Image: Macchiarini and Julia Tuulik, courtesy of SVT

However, the questions that have dogged Paolo Macchiarini are related less to disappointing patient outcomes, and more to the decision-making around operations. Had the risk of each operation been properly assessed? Were the patients ill enough to require such drastic intervention? Did the patients understand the risks involved?

Then there is a second set of questions that relate to the way Macchiarini has described the operations in academic publications.

After Beyene's death, four doctors at the Karolinska Institute began to have doubts about synthetic transplants, and about Macchiarini himself. The group included Karl-Henrik Grinnemo, who had assisted Macchiarini in Beyene's organ transplant operation in 2011, and Thomas Fux, who was involved in the aftercare of Macchiarini's patients at the hospital.

They alleged that Macchiarini had misrepresented the success of the operations, omitting or even fabricating data in his published articles.

KI's vice chancellor at the time, Dr Anders Hamsten, called in an outside expert, Dr Bengt Gerdin, from Uppsala University Hospital, to lead an investigation. In May 2015, Gerdin reported back, concluding that by-and-large the whistleblowers were right: Macchiarini was guilty of scientific misconduct.

But in August 2015 Hamsten and the KI management threw out Gerdin's report. Based on undisclosed evidence they had seen - which Gerdin had not - they reaffirmed their faith in the surgeon and extended his contract.

The Karolinska Institute's striking campus

In the end, it was not a scientist, doctor or lawyer that grounded Macchiarini's high-flying career, but a TV journalist.

Bosse Lindquist followed the surgeon for months for a documentary series for the Swedish public broadcaster, SVT.

Lindquist also scoured the world's media archives for footage of Macchiarini, and he was rewarded with a wealth of material. "It turned out that Macchiarini had always liked journalists and had often invited TV teams to his surgeries," Lindquist says.

Some of the most striking moments of the series come from these archive rushes.

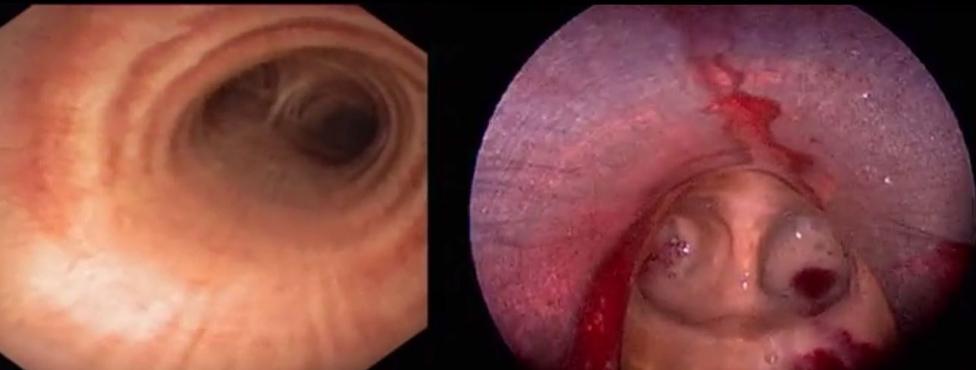

For example, Lindquist uncovered footage of Andemariam Beyene undergoing bronchoscopies, the procedure in which doctors view a patient's airways with a miniature camera. The footage from the surgical camera seemed to conflict with the descriptions of the patient in Macchiarini's published articles.

Instead of an "almost normal airway" the footage showed that a build-up of scar tissue was impeding the passage of air to the right lung. The clips also showed a fistula - a hole into the rest of the body - at the end of the trachea.

Bronchoscopy footage of a normal airway, and Andemariam Beyene's 12 months after his operation

The articles are currently the subject of yet another investigation. On Friday, the Central Ethical Review Board in Sweden ruled that a 2014 article by Macchiarini, published in the journal Nature Communications, involved research misconduct. The article described a transplant trial in rats, which, the committee ruled, was not as successful as had been implied.

The Review Board will rule on the other contentious articles soon. The 2011 article in the Lancet now carries an "expression of concern". The senior editor of the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research tells the BBC that his journal will issue a similar warning soon.

Macchiarini says that some mistakes were made in the preparation of the articles, but there was no intention to mislead.

Lindquist agreed not to ask Macchiarini about the allegations against him until the outcome of KI's internal investigation in 2015, but eventually the two men sat down for a long and very awkward interview.

The normally urbane Macchiarini becomes increasingly rattled as Lindquist presses him to answer why five human beings received plastic tracheas before any experiments checking the suitability of the scaffolds in animals were published.

At first, Macchiarini says that his team conducted animal studies before 2011 at KI, but they have yet to be published. When Lindquist points out that he has found no official approvals for such research, Macchiarini changes tack, asking, "How do you know that we didn't do animal studies in Russia?"

Finally the doctor admits in an irritated tone, "We didn't do any animal study that involves large animals - of course not, we didn't have the time. The material was proven, the material was studied. We used fibres that were approved by the FDA [the US Food and Drug Administration]. And now all the studies are coming."

Lindquist called his documentary series The Experiments. The implication is that Macchiarini was treating humans as guinea pigs, instead of doing preliminary research on animals.

Find out more

The Experiments will be broadcast in the UK as part of BBC4's Storyville strand in October 2016

Listen to Christine Westerhaus's radio report about the Macchiarini controversy, broadcast in February on the BBC World Service

When it was broadcast in Sweden in January, The Experiments caused a sensation, with about 15% of the population tuning in to watch this complicated medical story unfold.

Anders Hamsten stood down as vice-chancellor of KI, as did Urban Lendahl, the general secretary of the Nobel Committee. Macchiarini was fired, and half a dozen inquiries launched.

Last week, the Swedish government sacked all members of KI's board who remained in position.

Bo Risberg, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of Gothenberg and a former chairman of the Swedish Ethics Council, has called for the Nobel Prize to be suspended for two years as an "apology" to Macchiarini's patients and their families. He has said the events amount to the biggest research scandal Sweden has experienced in modern times.

"It is very strange that it should take a TV programme to make this public," Risberg said earlier this year. "Everything was swept under the carpet."

The failure to do pre-clinical tests on animals, he said, was "the worst crime you can commit."

In May, Macchiarini discussed his decision to operate, external on Andemariam Beyene on SVT. "We had a human being that we wanted to save," he said, "And in these circumstances what would you do? Do you just leave him dying at that young age? I don't think it's correct."

This touches on the blurred distinction between trying out a new treatment as part of a clinical research programme, and innovating in an emergency to save or prolong a life. The Swedish government is investigating whether guidelines differentiating the different scenarios need to be clearer.

Last week's report into the synthetic transplant operations that took place at Karolinska University Hospital concluded that while there was a compassionate element to the operations, they still involved clinical research. Therefore, Macchiarini should have sought approval from an ethical review board. "It is unlikely that the project would have been approved," the report notes.

Moreover, it states that there was no immediate threat to life for Macchiarini's three patients before the operations.

In an email to the BBC, Macchiarini says he accepts the findings of the report, but he adds that it was the responsibility of the hospital administration to apply for ethical permissions.

"I would welcome international discussion and clarification of the ethical processes to be undertaken in such difficult circumstances as these - where experimental treatments are involved," he writes.

"It is clearly a difficult area for clinicians and researchers to be involved in, and yet vitally important that new treatments are developed and tried…"

Macchiarini says that the report highlights "the very great amount of pre-clinical research that has been done into synthetic tracheal scaffolds", though he concedes that Andemariam Beyene was the recipient of an untested procedure.

"I would like to add that the welfare of patients has always been my driving concern. Although there may be criticisms of decision-making processes and administrative processes, and these may have had tragic consequences that with hindsight are deeply regrettable, everyone involved in the clinical care of these patients felt that they were doing their very best for these individuals. That should never be overlooked."

Macchiarini with colleagues in Krasnodar, Russia

When asked about the transplants, Macchiarini has often mentioned that he was not the only one responsible for the decision to operate, but discussed his patients in multidisciplinary conferences. "There were 30 or more professionals involved in the decision-making process," he told SVT, "and then even in the inter-operative and postoperative care of the patient."

Yet one of the most critical issues was not discussed in the meetings - whether there was enough scientific evidence to support the procedure.

Some experts claim that the entire project of growing human organs, although appealing to popular science journalists, is flawed.

Dr Pierre Delaere, a professor of respiratory surgery at KU Leuven in Belgium, has said that it is impossible for surgeons to establish a new blood supply to a trachea - donated or synthetic. Delaere has called Macchiarini's method "one of the biggest lies in medical history, because you are doing something that is impossible from a theoretical point of view".

The use of bone marrow cells has also come under scrutiny. "There is absolutely no evidence that these cells differentiate into mucosal epithelia (lining tissue) or blood vessels," says Leonid Schneider, a science blogger who trained as a molecular cell biologist and used to work in stem cell research.

"This claim that bone marrow cells can create any kind of tissue is based on old papers, which are long discredited by science, and every single stem cell scientist will tell you they cannot do it."

He adds: "Everybody switched off their brain. The stem cell scientists switched off their brains to the science, and the clinicians switched off their brains to the use of the plastic, which couldn't even be sutured into patients, and everybody went along with it."

Macchiarini maintains, in his email to the BBC, that "there is no doubt that it is a viable technology". He adds that he is continuing his work with biological scaffolds, expanding his focus from the trachea to other organs.

A public prosecutor in Stockholm is currently gathering as much information as she can about the three operations that took place at Karolinska University Hospital, and says she will decide next year whether to press charges equivalent to manslaughter and grievous bodily harm.

The hospital is already the subject of two police investigations, triggered last year by complaints from government healthcare agencies.

Despite his many appearances in the media, the man at the centre of the scandal remains something of an enigma.

By chance, the transmission of The Experiments in Sweden coincided with the publication of an article in Vanity Fair in which it was alleged that Macchiarini had had a relationship with a television producer who was making a film about him. The story alleged that the producer had ordered her wedding dress before learning that Macchiarini was married with children.

Macchiarini has declined to comment on the story.

"He's an exceptional person for sure, and he has this faculty for stretching the truth just the right amount," says Bosse Lindquist.

"But in order to be able to seduce the medical community you need to have a whole host of professors who would like to be seduced and who would like to believe that the Nobel prize is very close, or you can make lots of patent money, for example, or corporate money.

"I think he has an acute ability to suss out the faults and cracks in the system where he could manoeuvre."

Additional reporting from Christine Westerhaus. Listen to Christine Westerhaus's report on the Macchiarini scandal, which was originally broadcast in February 2016 on the BBC World Service. The Experiments will be broadcast in the UK in BBC4's Storyville strand in October.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.