'How I accidentally became a poet through Twitter'

- Published

Brian Bilston has been dubbed the "unofficial poet laureate of Twitter", but he stumbled into writing poetry on social media. Here he explains the power of online verse.

It started with a tweet. I never thought it would come to this.

I'm not even sure it was a poem. More of a play on words, each one carefully selected to fit into the 140-character constraint of a tweet.

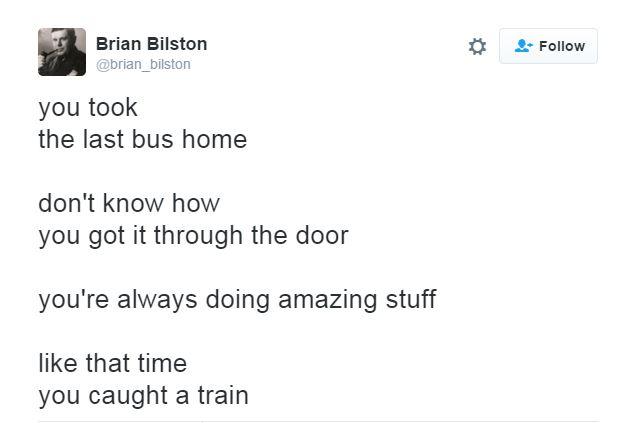

It went:

I sent it out - and then went out. By coincidence, to see a poet - a proper one, the poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, no less - who was giving a reading nearby.

I had turned off my phone so it wasn't until a few hours later, when I'd returned home and turned it back on again, that I saw my Twitter notifications had gone crazy - my tweet had been shared several hundred times, I had 200 new followers. It was the kind of reaction I was utterly unaccustomed to getting.

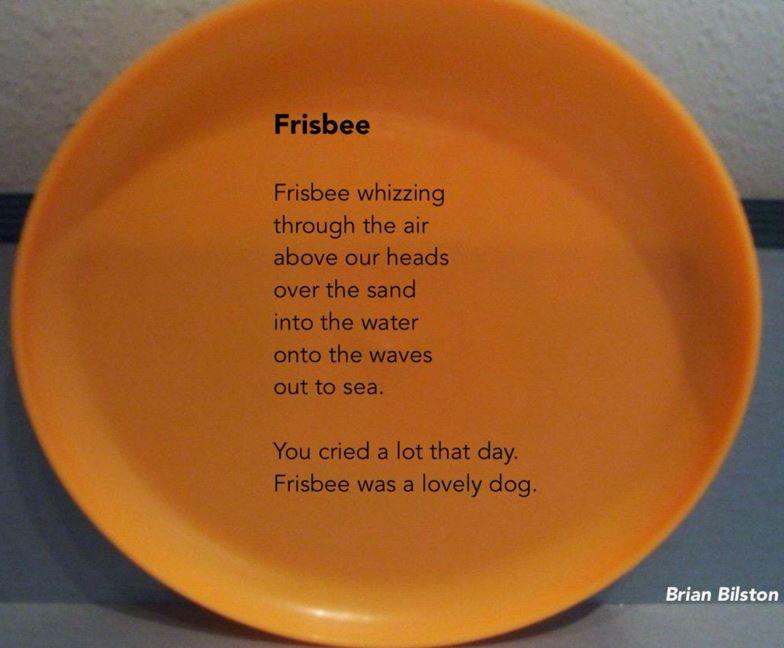

A few weeks later, I tried again. A poem entitled Frisbee:

Again, it was well-received. More retweets. More new followers. And so my career as social media poet began.

I had never intended to be a poet. A poet to my mind was someone of intensity, a serious type, the kind of person you wouldn't want to get trapped in a kitchen with at a party (if poets received invitations to parties at all, that is).

I vaguely remembered the term "iambic pentameter" from my schooldays. I knew roughly how many syllables there were in a haiku, and I had a rudimentary grounding in the poetry of Eliot and Larkin - although my true heroes were Roger McGough and Ogden Nash.

Find out more

This is an edited version of The Social Media Poet, part of Radio 4's Four Thought series - catch up on BBC iPlayer Radio

I had never intended to waste my days on social media either. Of Twitter, I was, as with so many other things, a late adopter. I had only joined it in order to understand what it was that those people at work, invariably younger than I, would talk about so irritatingly in meetings.

So I joined, and like many other first-time tweeters, those early months were spent in writing bad jokes and puns which echoed in the ethereal emptiness.

But something else had begun to bloom in the background - I had started to talk to strangers on Twitter (some of whom were very strange) and read about the things that interested them or made them laugh or annoyed or sad or angry.

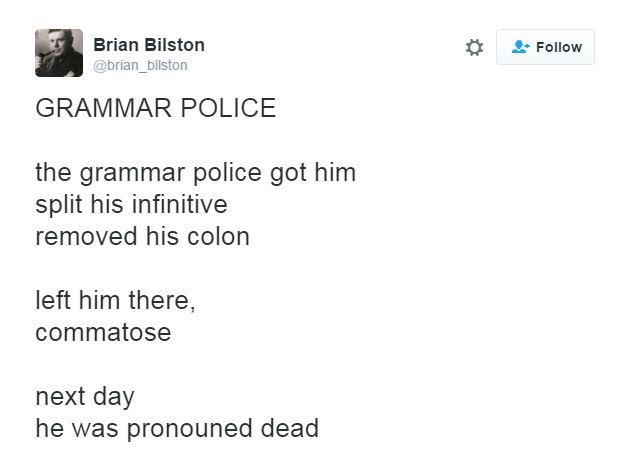

And almost nothing, it seemed, made Twitter angrier than bad grammar. For every badly spelt, poorly constructed tweet, there were a hundred unreconstructed grammar pedants leaping in to point out the mistakes.

So I started writing poems about these heinous crimes, the misapplication of a semi-colon, the rule about i before e, and of course, that most controversial of all the punctuation marks, the Oxford comma - and even gently mocked the grammar enforcers themselves:

I began to receive feedback on my poems from Twitter users. A typical response was: "I hated poetry at school. I never thought I'd find myself retweeting a poem."

Or: "I don't really like poems but I like whatever it is you do"

I am still unsure as to whether these are compliments or not. But it did open my eyes to how poetry is still viewed with suspicion by a large part of the populace, in spite of the undoubted resurgence in popularity it has seen in recent times.

We see signs of that new interest in poetry all around us - the growth of performance poetry and the spoken word movement, poetry slams, workshops for aspiring poets, the soaring membership of societies at the national and regional level, the rise of self-publishing, and a new generation of inspiring younger poets, such as Kate Tempest and George the Poet, taking the form to newer audiences.

Kate Tempest

But move outside of that growing community, the impression remains that poetry - in general terms - is difficult, almost deliberately obtuse and obscure, frequently dull, and willfully uses words such as "crepuscular" or "obsidian".

Small wonder that the business of publishing poetry books is a fraught one - few titles sell in substantial quantities, and most general commercial publishers or literary agents have turned their backs on poetry.

Books are published by specialist presses with short print-runs or self-published. Poetry sections in bookshops appear to shrink by the month. There's a lot of poetry about but it seems few people want to buy it.

But social media shows us that a broader, more democratic appetite for poetry exists, after all.

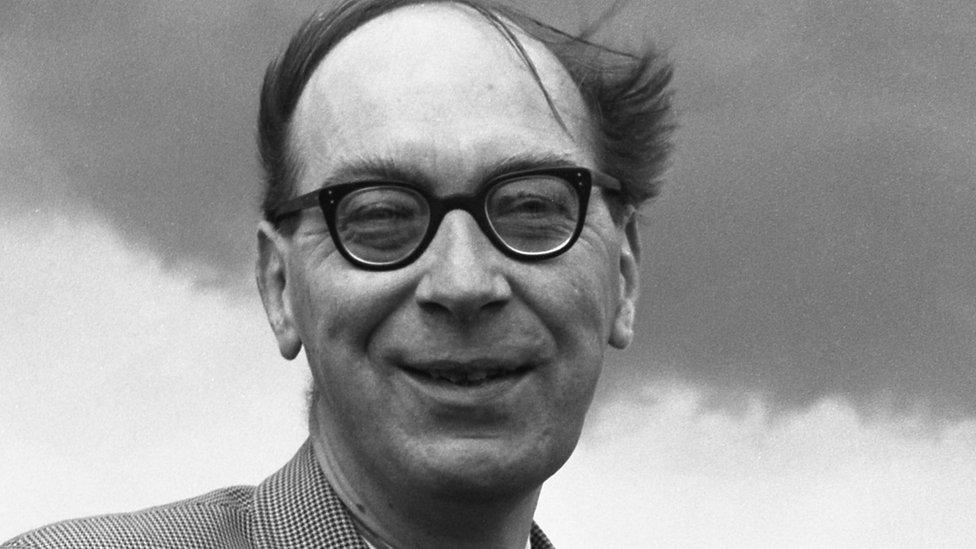

In June, as the terrible news came in of the murder of MP Jo Cox, the Poetry Society - a UK organisation with the aim of promoting the study, use and enjoyment of poetry - shared on Twitter The Mower, external, one of Philip Larkin's later poems.

The poem concerns the death of a hedgehog, jammed up against the blades of his lawnmower. The poem is mournful and melancholic but also compassionate and powerful.

It travelled around Twitter at lightning speed, bursting out from the bubble of The Poetry Society's followers to find a much broader audience. It was re-shared over 3,500 times and reached a readership of half a million readers in just a few days.

It's a piece that does what brilliant poetry does best - it moves us, it gives voice to thoughts and feelings that we ourselves may struggle to articulate, it's personal and yet universal.

Philip Larkin

But also, 37 years after it was written, it is relevant. It's Poetry as Current Affairs. The Poem as Social Commentary. And that can be the power of social media for poetry - a place to share words at the point of need. It is lent an immediacy other outlets for poetry do not have - it is not trapped in the pages of a book on a shelf, nor waiting to be recited at an event taking place two weeks next Thursday. It's there where we need it - and when we need it.

But the relationship between poetry and that broader social media audience is more than an immediate, articulated response to tragedy. A platform such as Twitter can also serve as an endless source of ideas for poets.

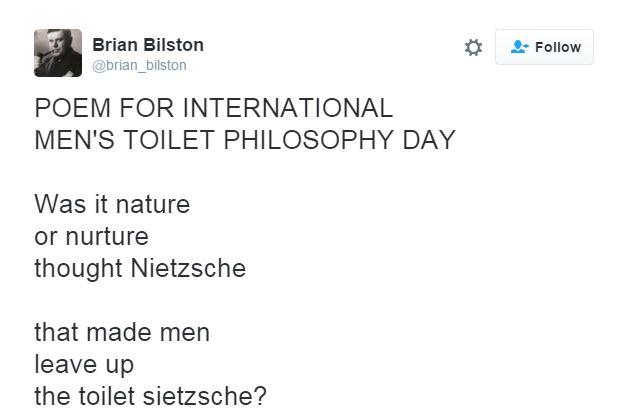

Without Twitter's hashtag, the symbol for what is trending at any moment in time, I would never have known about Penguin Awareness Day or National Stationery Week. Last year, the stars aligned and three celebrations occurred all on the same day - World Philosophy Day, International Men's Day and World Toilet Day, giving rise to this short piece - Poem for International Men's Toilet Philosophy Day - which combines all three:

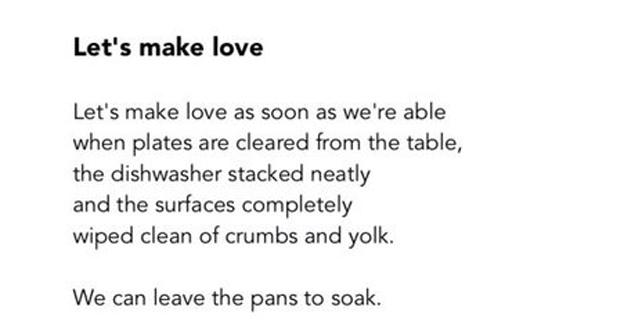

Poetry is often seen as being about Universal Concepts and Big Ideas - Truth, Love, Death, Beauty, Betrayal, Regret. These are all Grand Themes upon which we have cause to reflect throughout our lives. But there's poetry to be found in the stuff of everyday existence, too - that nonsense in our lives that sometimes gets in the way of those Grand Themes - and social media is the ideal arena in which to share it.

There are other lessons for poets to learn from social media about how to keep their writing interesting and relevant to modern audiences. The ways in which we consume content have begun to change.

Any time spent wallowing in the mire that is social media shows how visual the information is with which we now engage - yes, there are words aplenty, but there are pictures and videos, too.

The barrage of information that is thrown at us means that plain words on a page are becoming less likely to be read. People struggle to find the time, inclination or powers of concentration to wade through pages of dense text. Words find themselves in competition with pictures. And less is often more.

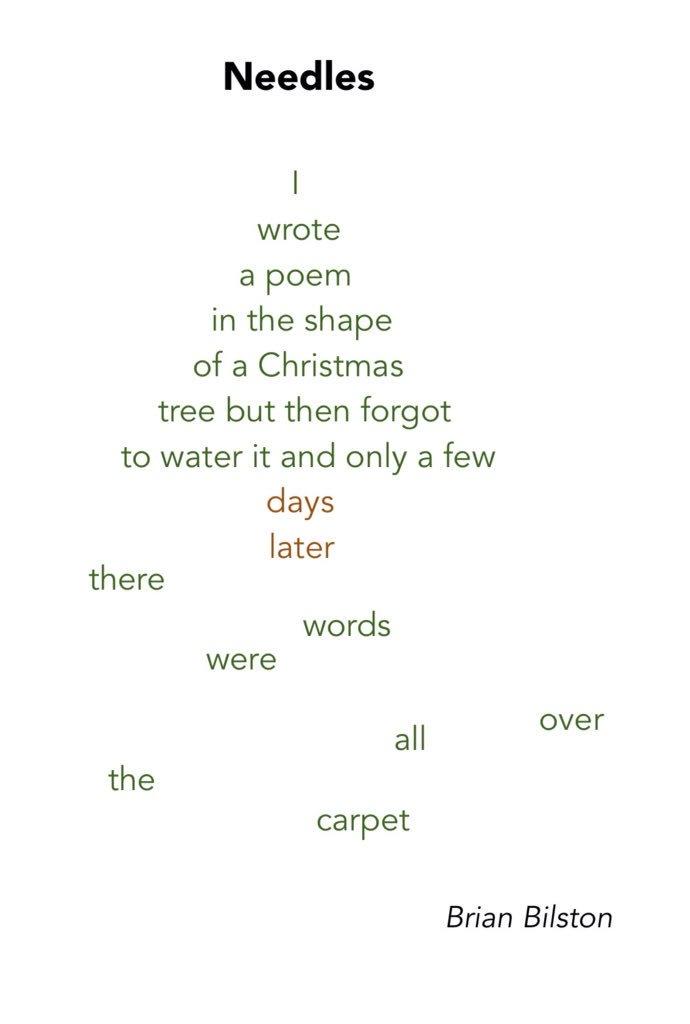

But poets shouldn't feel threatened by this in a social media setting - rather, it gives us the opportunity to think about form as well as content, and how the presentation of a poem might enhance or complement the words which accompany it.

I began to experiment with the visual aspects of poetry, when I wrote a poem in the shape of a Christmas tree. The poem itself was about how I had neglected to water my words, and I illustrated this by having words spread out around the base of the poem, like pine needles scattered over a carpet.

The presentation of the poem was the punchline but also enabled it to stand out amongst the hundreds of other tweets sitting on users' timelines.

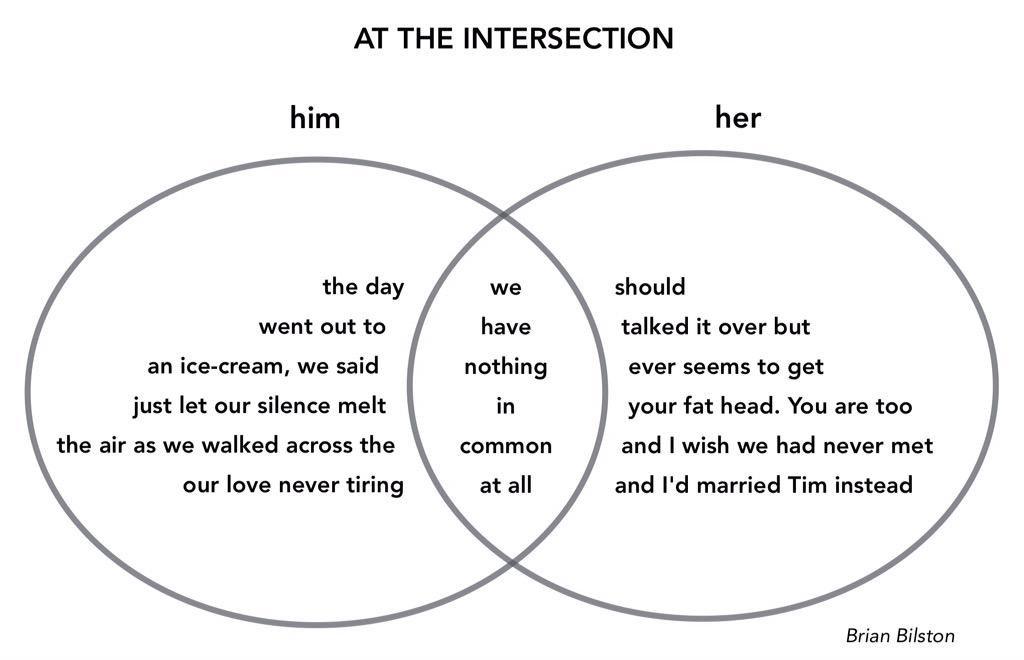

Other forms and shapes followed. We live in an age of infographics, data, flowcharts. On Twitter, I noticed how everyone, it would seem, enjoys a good Venn diagram. So I wrote a poem using two different personal narratives separated into two halves of a Venn diagram, with words which overlapped in their stories appearing in the intersection to form a third, unifying perspective to the poem.

And from there followed poems in flowcharts, or made from Scrabble tiles, in Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations, in the form of CVs, in the shapes of wine-glasses and light-bulbs. They all became popular.

Yes, their novelty helped the poems stand out - but they also embedded words within places or situations that people recognized from their own lives.

So what have I - as an accidental poet - accidentally learnt?

Poetry on social media is more than a never-ending stream of haiku concerning the changing light of the moon on water, or the beauty of cherry blossom.

It's far more interesting and relevant than that.

More about Brian Bilston

'Banksy poet' on Trump, sex and the Mail

It's an opportunity for poetry to present itself in situations where and when people most need it - as a way of finding meaning or comfort to bigger, often unfathomable, world events, perhaps, or simply to provide some light relief from the complexity and perplexity of life.

But it's also a platform for poets themselves to interact and engage with their audience - and, indeed, find new audiences - through experimentation with content and form, and a deeper engagement with real world concerns.

I shall finish with one more poem, written one day when Twitter became unavailable for a whole afternoon, much to the angst of millions of people around the world. It's called The day that Twitter went down.

That day I got things done.

I went for a long run.

Played ping-pong,

Wrote a song.

It got to number one.

That day I did a lot.

I tied a Windsor knot.

Helped the poor,

Stopped a war,

Read all of Walter Scott.

O what a day to seize.

I learnt some Cantonese.

Led a coup,

Climbed K2,

Cured a tropical disease.

That day I met deadlines,

Got crowned King of Liechtenstein,

Stroked a toucan,

Found Lord Lucan,

Then Twitter came back online.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external