Can India really halve its road deaths?

- Published

India has some of the world's most dangerous roads. Last year nearly 150,000 people died in traffic accidents, an increase of 50% in the past decade. But the government insists it can halve this figure in two years, while also embarking on one of the biggest road-building programmes the world has ever seen.

For a crash course in India's car-crash culture, go to Mumbai. There are more accidents here than any other Indian city. You'll witness a dangerous mix of pedestrians, scooters, cars, buses and lorries jostling through choked junctions. Many ignore both signals and the traffic police.

Officers can do little about such rampant law-breaking.

"We can catch a maximum of two offenders at a time - maximum," one shouts at me above the horns and revving engines at one particularly busy junction. "The rest," he says flicking his wrist, "just go. There are no consequences."

Mumbai: "A dangerous mix of pedestrians, scooters, cars, buses and lorries"

Mumbai's commissioner of traffic police, Milind Bharambe, says this will soon end. From his cool office, flanked by monitors with live CCTV feeds of notorious accident spots, he explains how cameras will enforce the law electronically, targeting those who speed and run red lights. Combine that with the recent introduction of stiff new fines and within six months, he promises "a sea change" in driver behaviour.

Milind Bharambe, Mumbai's commissioner of traffic police

But bad driving and weak enforcement are only part of the problem. Another aspect of it is the rapidly growing number of vehicles - a new one joins the chaos every 10 seconds. It adds up to almost 9,000 new vehicles a day, or more than three million a year.

This means that the streets are increasingly choked. It's almost impossible to leave a safe distance between vehicles, and when space does open up, frustrated drivers often respond by putting their foot down.

Find out more

Neal Razzall presents Fixing India's Car Crash Capital on Crossing Continents, at 11:00 BST on Radio 4 - catch up on BBC iPlayer Radio

The problem is perhaps most acute in Mumbai, which is surrounded by water on three sides and has little room to grow. Officials here have in the past responded to the crush of cars by tearing out pavements to make room for more.

"The government still thinks the major issue is 'How do we move people in cars faster and quicker?'" says Binoy Mascarenhas from the pedestrian advocacy movement, Equal Streets. In reality, he says most journeys are local and, in theory, can be done on foot.

Pavements are often non-existent on Mumbai roads

In theory. He grew up in Mumbai, and used to walk to school. His daughter now goes to school in a car because it's too dangerous to walk. Pavements, where they exist, are often in such a poor state people have to walk on the roads. No wonder then that pedestrians account for 60% of road deaths in Mumbai.

There are dangers outside the city, too.

India's first expressway, between the cities of Mumbai and Pune, opened in 2002. It has three wide lanes and room to move at high speed - a relief after the congestion of the city. But drive it with one of India's few professional crash investigators, Ravishankar Rajaraman, and a quiet terror settles in. He's studied thousands of crashes on this road and can point to dangers all around.

What makes Indian roads so dangerous?

"There are small, man-made engineering problems that are actually killing people," he says. Instead of rumble strips to warn drivers they're at the road's edge, there are black and yellow curb stones embedded into the concrete. Hit one of those, Shankar says, and your car can flip over. Then there are cliffs with no barriers, and guard-rails with tapered ends, which, he says, can send cars into the sky "like a rocket launcher".

Things like this are happening all the time. The expressway is just 94km (58 miles) long but about 150 people die on it every year.

"That's serious. That's a very bad number," Shankar says.

He and his colleagues at JP Research have identified more than 2,000 spots on the expressway where relatively simple engineering fixes, from better barriers to clearer signs, could save lives.

Crash investigator Ravishankar Rajaraman examines the wreckage of a fatal car accident

"Road engineers are not serious about this problem," Shankar says. "So we keep fighting with them on this point. How many deaths are you going to wait for, until you really understand that this is a serious concern?"

In this context, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's plan for the biggest expansion of roads in Indian history is unnerving. In the next few years he wants to pave a distance greater than the circumference of the earth and there's a particular push to build highways and expressways.

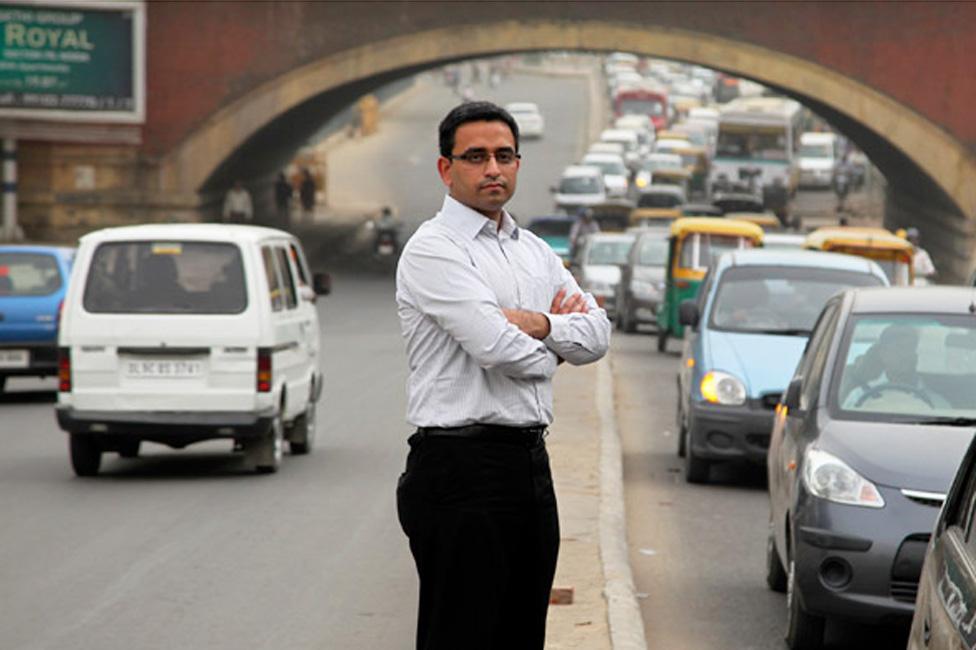

Piyush Tewari, CEO of the SaveLIFE Foundation, says that without putting the country on a "war footing", including a complete overhaul of road safety legislation and a modern road-building code, Modi's new roads will only add to the number of dead.

"Road crash deaths will increase at the rate of one death for every 2km of new road that is constructed. That's the average death rate on Indian highways - one death every 2km, annually. So if we don't fix any of this, if we're constructing 100,000km of highways, 50,000 deaths is what the average maths tells us will be added to the total," he says.

Piyush Tewari believes the planned new roads could lead only to more fatalities

Modi's government insists the new roads will be safer. "We are improving the road engineering; we are improving the traffic signal system; we are making crash barriers", transportation minister, Nitin Gadkari, tells me.

There is progress in other areas too. When Mumbai's commissioner of traffic police predicts a "sea change" in driver behaviour he is partly putting his faith in a new motor vehicle bill, now before parliament, which if passed would increase fines, toughen vehicle registration requirements and mandate road-worthiness tests for transport vehicles.

And earlier this year, a Good Samaritan Act came into effect which ended the crazy situation whereby people who helped crash victims could be held liable for the costs of treating them or even accused by police of causing the crash in the first place. That alone, campaigners say, will save thousands of lives.

More from the Magazine

When a road accident occurs, bystanders will usually try to help the injured, or at least call for help. In India it's different. In a country with some of the world's most dangerous roads, victims are all too often left to fend for themselves.

If no-one helps you after a car crash in India, this is why (June 2016)

The SaveLIFE Foundation estimates that half of all road deaths are the result of treatable injuries. That means 75,000 lives could be saved every year just with better medical care.

One man trying to save some of those lives is Mumbai neurosurgeon Dr Aadil Chagla, who is working with volunteers to build a series of clinics along Highway 66, south of Mumbai - many of them in rural areas - to prevent victims having to be driven for hours to the city.

The first is more than half-built. It looks out over rice paddies and lush hills, but Dr Chagla estimates it will be treating victims from "one or two crashes a day, every day".

"If I can have an ambulance service and trauma centres every 50 to 100km run by the locals it would make huge difference to this entire highway - with or without government support," he says.

Dr Chagla's as-yet-unopened clinic to treat victims of road accidents

Since Dr Chagla started practising in the 1980s, the number killed on India's roads has increased by 300%.

"I waited all this time and nothing has really come through so it's important that I should do something about it," he says.

So if transportation minister Nitin Gadkari is to make good on his promise to cut road deaths from 150,000 to 75,000 per year in two years, it will be thanks in part to the efforts of volunteers.

The state corporation that owns the Mumbai-Pune Expressway, meanwhile, says it will reduce deaths to zero - yes, zero - by 2020. It has accepted the list of essential improvements identified by crash investigator Ravishankar Rajaraman and authorised them to be made and then audited by the SaveLIFE Foundation.

But there's a snag, which suggests India is not yet on a "war footing" when it comes to safety.

The state government owns the road, but a private company runs it in exchange for collecting tolls. The two sides dispute who should make the safety upgrades. The official in charge of the expressway says the work will be done, even if it requires litigation to recover the costs.

While the dispute drags on, 100,000 vehicles use the expressway every day in its current, dangerous state. In the past week, it claimed six more lives.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external