'Too black, too strong': The Woodrow Wilson Tigers' national anthem protest

- Published

In 2009, Preston Brown gave up the dream of playing professional football for the NFL and moved back to his hometown of Camden, New Jersey. He did it with a single purpose in mind: to help poor boys like he had once been.

As the head coach of the Woodrow Wilson High School Tigers, he took on the 24-hour-a-day job of being a mentor and a father figure to 68 young men and boys who are growing up in one of the poorest cities in the US. The 31-year-old spends his own money to feed them when they're hungry. He gives them a place to stay when they have nowhere to go.

So why do so many strangers want him out of a job?

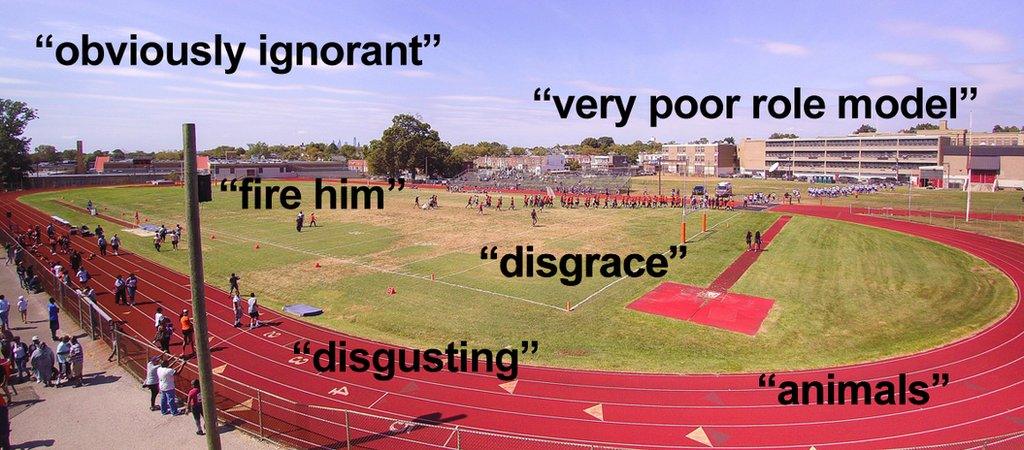

"You are a disgrace to your high school and a coward."

"I will help them fire you … I hate you with all my heart."

"Get the f*ck out of this country if you don't like it you anti-American asshole."

Brown - a married father of three - wakes up every morning to emails, Facebook messages and voicemails questioning his intellect, his humanity, his patriotism.

For the past two weeks, the Camden City School District has received dozens of calls from across the country, calling for Brown's dismissal. A local radio personality denounced his "ignorance, shame and stupidity" on the air.

The sin that Brown committed: on 10 September, at the Woodrow Wilson Tigers' first game of the season, Brown refused to stand for the playing of The Star-Spangled Banner. Instead, he took a knee in a silent protest.

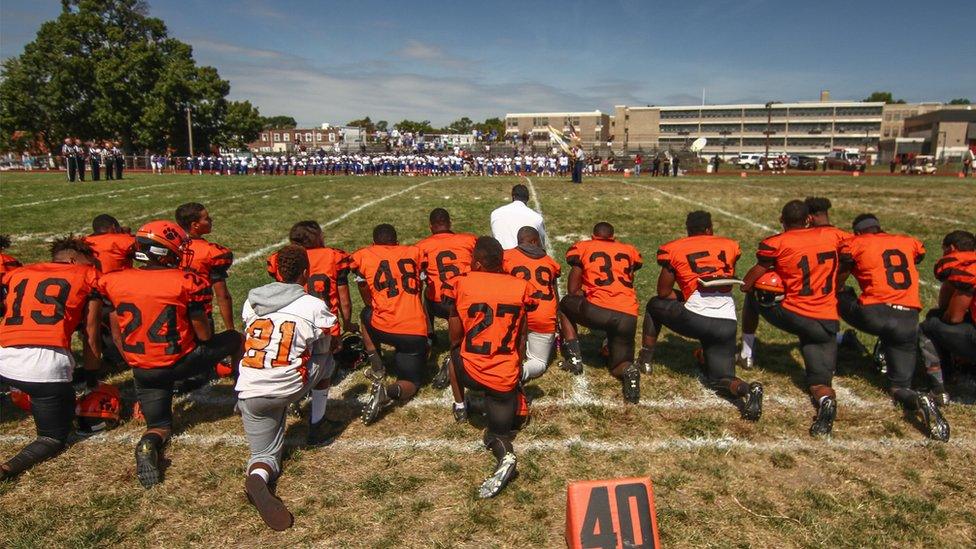

With the exception of two players, the entire Tiger football team joined him. A local sports reporter captured the incident on video - a row of players kneeling in their black and orange uniforms - and posted it online. By evening, the story had gone viral.

"I honestly did not know or feel like anybody would've cared if we kneeled," says Brown. "I really didn't think it was going to be a big deal at all."

Seated in one of many worn and broken chairs in the messy coaches' offices behind the high school, Brown - six foot four, still built like the receiver he was in his playing days, head shaved smooth - says the abuse has been directed at the players as well.

They've been called "animals," "illiterate", "dirtbags".

Brown has received ominous voice messages from a caller promising he's coming to the Tigers' next game.

"I'm an adult. I can handle it," he says.

"But the fact that all these people would say all these negative things to try to destroy the mental makeup of these young people that I stand in front of and I love with everything inside of me…"

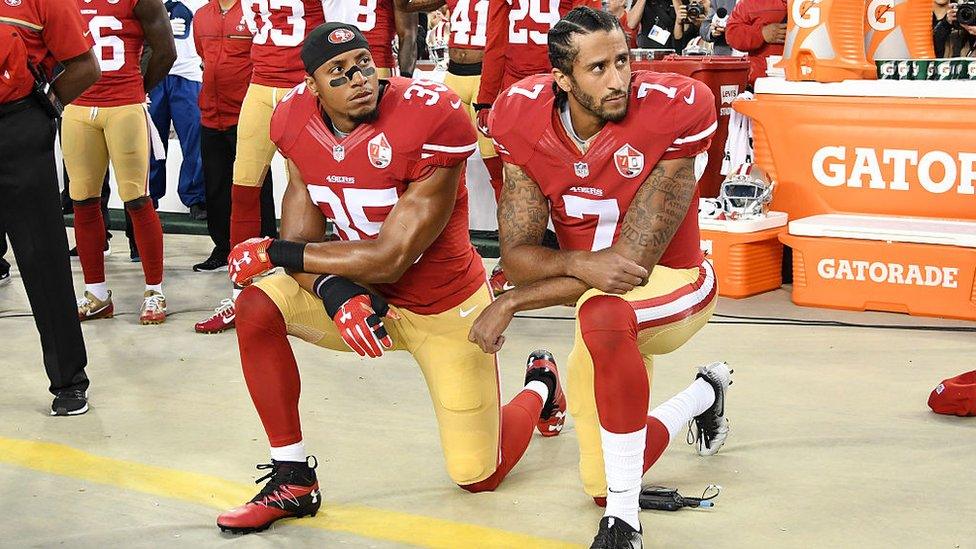

The protest was, of course, inspired by Colin Kaepernick, the backup quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, who refused to stand for the national anthem on 26 August and at every game since.

"I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour," Kaepernick said. He cited recent incidents of police killings of black men, women and children, like Walter Scott, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice.

Police officials condemned the remarks and the protest. One sports analyst sniped that Kaepernick's job is to "be quiet and sit in the shadows".

Many - including Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump - slammed Kaepernick for his lack of patriotism. "Maybe he should find a country that works better for him," said Trump.

Still, Kaepernick's protest began to spread. On the following game day, San Francisco safety Eric Reid joined him, as did Jeremy Lane of the Seattle Seahawks. Most players, including Kaepernick, decided to take a knee during the anthem instead of sitting.

By the following weekend, players on the Seahawks, Miami Dolphins, Kansas City Chiefs, New England Patriots, San Francisco 49ers, and Los Angeles Rams protested in some fashion, whether it was kneeling, raising a fist or linking arms.

Players whose games fell on 11 September participated, regardless of the fact it was the 15-year anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Student athletes began following Kaepernick's lead - a lone black player on a team in Brunswick, Ohio. An all-black pee-wee team in Beaumont, Texas. And an entire team, and its coach, in Camden, New Jersey.

While critics mocked Kaepernick for being a multi-millionaire complaining about injustice, teams like the Woodrow Wilson Tigers - which is made up entirely of black and Hispanic players, in a school where 85% of the students qualify for the state's free lunch programme - are actually living in places where, for a number of social and economic factors, the odds for success are stacked against them.

"I think it is indisputable that if you are born black and Latino in a city like Camden you have a far steeper mountain to climb to enjoy the same freedoms as the rest of our country," says Paymon Rouhanifard, the Camden City School District superintendent.

"I can't speak on each student's behalf, or the coach's behalf, but that's what I believe they are trying to raise."

Coach Preston Brown on protesting during the national anthem

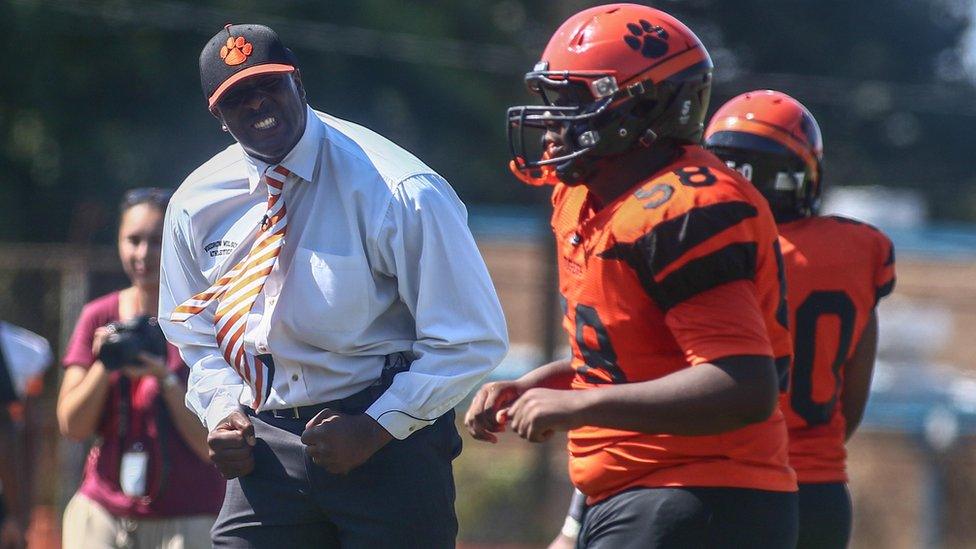

On a sunny, temperate Friday afternoon, Coach Brown watches students as they stream down the front steps of Woodrow Wilson High School.

It's a slightly run-down but still beautiful three-storey building with art deco chandeliers hanging over the metal detector at the entrance.

"Stay out of trouble this weekend," Brown calls after them. "Take it easy. Leave that hat at home next week."

Brown towers over the kids in a snappy grey suit and tie. He slowly makes his way through the throng towards the athletic fields and runs into a group of his players on their way to the corner store.

"Can I get a water ice?" he asks them, pulling a $10 bill out of his wallet. "Get all them something, just bring me like, at least $3 back."

He chuckles, watching the boys run off.

"Trust me, $5 around here can go a long way."

Little has changed about the school since Brown was a student here 15-odd years ago.

The student body is still overwhelmingly black and Hispanic - last year, only three of the 881 students who attended were white. Historically, less than half of its students graduate, although in the last few years that number has improved from 49% to 64%. New Jersey Monthly ranked it 331st out of 337 schools in the state.

When education officials announced a state takeover of the Camden city school district, calling it a "human catastrophe", they held the press conference in the Woodrow Wilson library.

In his day, Brown stood out for being a straight-A student and the National Honor Society president, graduating in 2003 with a full scholarship to play football at Tulane University. He achieved what so many kids in Camden dream of: he got out.

"When you are big in sports around here, they always tell you, 'Hey, go out, do your thing and don't come back,'" he says between bites of rainbow-coloured frozen ice. "'You don't need to come back here, ain't nothing for you here.'"

About 40% of Camden's roughly 77,000 residents are living below the poverty line. Despite the fact that major developments like a new Philadelphia 76ers basketball stadium and a Subaru plant are coming to the city, those dollars have yet to trickle down into some of the city's toughest neighbourhoods, like East Camden, where Woodrow Wilson is located.

While Chicago grabs the most headlines for its problem with gun violence, the murder rate per capita in the city of Camden is actually more than twice Chicago's.

Despite all that, Brown came back. Six years ago, he returned with his wife, his kids and his master's of education degree, and began coaching at his old school.

Last year, he left his job as an insurance advisor and financial planner at Mutual of Omaha to become the high school's Dean of Climate and Culture.

He oversees student discipline as a part of the district's new plan to drastically reduce the amount of out-of-school suspensions and put an end to the so-called "school-to-prison pipeline".

Brown has never been a fan of The Star-Spangled Banner, not since his Haitian grandmother taught him about the often forgotten third verse: "No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave".

When he saw Kaepernick's protest, Brown thought about the fact that 2016 marks the 100th anniversary of President Woodrow Wilson's order that The Star-Spangled Banner be played at military and other official state events - the same pro-segregation president for whom his high school is named.

"It was just playing on my mind, I was like, '[Kaepernick's] worth $60m and he took a knee to risk it all for people like me, for people like the students that I see every single day,'" says Brown.

"I was like, 'I have to do this. I have to do this.'"

When he took the knee that Saturday, he did it with his back to the team. At practice the previous Friday, he told the boys that he did not expect them to kneel with him, but that if they did so, they should do it for their own reasons.

He didn't see that all but two of his players knelt with him, including the offensive line coach, an Air Force veteran.

"It's no disrespect to America," Brown says. "It's saying that Camden, New Jersey, and places like it and people who look like us, we're hurt. And we've been hurt for a very long time."

In the gymnasium at the rear of the building, a group of football players sit or lay in a row against the wall, eating snacks from the bodega, messing around on Snapchat and waiting for practice to start.

Daniel Medina stretches before the game

The boys have all read the online comments about them: they're all destined to fail or go to prison, that their school is nothing more than a penitentiary, that Camden is a hell-hole, a third world country.

"They have so much hate towards us," says senior offensive lineman Daniel Medina.

"To me, it's just motivation for us to go out on the field and do better," says Nasir Santos, who plays wide receiver.

"They don't have to worry about coming to school being in the middle of a drug transaction and stuff like that. So the most that they think of it is, 'Oh they being disrespectful, disrespectful black kids once again,'" adds Travon King, a junior wide receiver/defensive end.

"They don't see what we go through every day,"

During a recent practice, shots rang out just a block away from the Tigers' field. Students paused momentarily - watching as two women ran through a nearby yard - then went back to their exercises. Many of the boys know someone, or multiple people, who have been shot.

Last year, one of their teammates, Ja'Meer Bullard, was shot to death near his home in the Whitman Park section of Camden. He was being scouted by a slew of colleges including Rutgers and Temple University - on the cusp of "getting out".

The players don't discuss him much, in part because Bullard's two brothers are still on the team, in part because it's just too painful.

When the boys talk about why they knelt, they talk generally about injustice, about the news of police killings in other parts of the country.

In their own lives, the examples that come easiest to them are times when they've been followed around a store under suspicion of being a thief. They're less apt to talk about the kinds of things they're facing at home, but Coach Brown knows those struggles intimately.

"The first year, myself and the other coaches, we paid out of pocket $5,000 throughout the season to make sure we had the kids fed," says Brown.

Coach Brown on the sidelines

When the students complain they've only had Pop Tarts for dinner, Brown stocks up on chicken, hamburgers and hot dogs, and pulls an old grill out of the coaches' office.

Brown also reaches into his own pocket to take the students on college visits and football camps.

He works his contacts at various universities to get scouts to come out to Woodrow Wilson - since last season, 11 of his players have received full-ride scholarships to Division 1 schools. He views this work as nothing short of saving lives.

"Here in Camden, people have to understand that coaching - you become the father for a lot of these fatherless young men," he says. "A lot of them are sensitive to issues of manhood, because outside of these walls they don't experience it."

Brown has vivid memories of sleeping on the floor of his grandmother's one-bedroom apartment with his five siblings after his family was evicted yet again. He remembers eating mayonnaise sandwiches, and running extension cords through the yards from a neighbour's house in order to power a single lamp when they couldn't afford the bill.

He remembers wondering why his apartment had three stoves, and only realising when he got older they were being used to make powder cocaine into crack for the local drug dealers.

Later he would stand outside of the Camden County Jail, signalling "I - LOVE - YOU" with big swoops of his arms to his mother, watching through one of the tiny cell windows.

Football was Brown's salvation, and his saviour was an unlikely one. When he was 12, a neighbourhood drug dealer decided that Brown needed structure in his life and paid the $100 registration for his first football league.

Today, Brown tries to extend the same lifeline.

Tamir Moore, the team's quarterback says he'd like to be a police officer

That's what he did for 18-year-old Daniel Medina. Before Coach Brown pulled him aside during his gym class and signed him up for the Tigers, Medina was spending a lot of time in the streets, hanging around with gang-affiliated people.

"After school, I used to be outside, come home late. Ever since I started playing football, it's just straight school, football practice, then go home," says Medina. "That's why I look at him like a father figure."

Medina's mother Cruz Alvarado was until recently working the late shift at an aluminium factory and was often unable to keep a close eye on her son. She says she's seen a shift in him since he came under Brown's wing.

"I've never seen him go hard for something like I see him now with the football. He's more responsible with things," she says, saying his schoolwork has improved as well.

Brown knows that an NFL career is not a practical life plan for most of the students, and stresses the importance of using sports as a means to getting a free education en route to another career.

A handful of the players say they'd like to enter law enforcement.

"I feel like there's good police and there's bad police. There's a lot of injustice and stuff, but at the end of the day, however you look at it, they're risking their lives for your kids," says Tamir Moore, the team's quarterback, who hopes someday to walk a beat in Camden or Philadelphia.

At the Friday afternoon practice, there is no explicit talk from Brown about whether or not the team will take a knee. Everyone who did it last week already knows they will again.

Saturday, game day, dawns bright and clear.

Brown is up by 4:30 am. By 7am, he is opening up the field at Woodrow Wilson where a loathed flock of Canadian geese are pulling their breakfast out of the field.

"They're killing our grass," he mutters. "There'll be 40 more that'll show up."

Dressed in a Tulane Football shirt, Brown climbs into his dark grey Ford Escape, turns up the music, and drives across town. As he turns down the 1100 block of Mechanic Street, he slows down and changes the track:

There ain't much that you can do that I can't do for me/I already got my team/I tell 'em /We good, we good, we good, we good

Brown pulls over across from a weedy vacant lot, and leaves the engine humming.

"This is the street that my brother got killed on," he says. "[When] I ride past here, I usually play that song 'We Good' by Fabolous because, you know - just trying to remember and just let him know our goal, our mission is still the same thing - for us to be great."

In 2011, Brown's brother Antwuan - nicknamed "Poppy", the baby of the family, the one who stuck closest to their mother's side - was shot and killed while sitting in his car.

Brown was about to meet up with his little brother, to loan him some money so he could take his girlfriend to the movies. Antwuan was 20 years old.

"As the older brother, I just felt like I went wrong somewhere," he says, his voice suddenly weaker. "I had saved so many other young men before, but my baby brother was killed."

Antwuan Brown was murdered on the same street as Tiger player Ja'Meer Bullard, and Brown has made a kind of ritual out of driving down Mechanic Street before each Tigers game.

He sits for a few moments, and then he's off again, back to East Camden, to give his left tackle a ride to the game.

The day's opponent is a team from Northern Burlington County Regional High School, a rural school about 45 minutes from Camden, close to the US Army post known as Fort Dix and McGuire Air Force Base. About half of the students at Northern Burlington have a family member serving in the military.

When the Northern Burlington Greyhounds arrive, some of the players are wearing American flag-themed socks. Their parents describe this as the team's "statement" on the Tigers taking a knee.

The predominant attitude on the visitors' side seems to be that kneeling is inappropriate. "Disrespectful" is the word that comes up over and over again, though no one is anxious to say much more, or give their names.

The people who do want to talk are more measured.

Liz Hennessey, the mother of a linebacker, cheerfully twirls a dollar store noisemaker and says that as the wife of a first responder, her only objection was the fact that football players wouldn't stand for the anthem on the anniversary of 9/11.

"I don't think I would take it so offensively any other weekend," she says. "They're trying to make a response to what happened in their lives and their neighbourhoods - I don't have a problem with that."

Bill McRoberts - another Northern Burlington parent who happens to know Coach Brown - is exasperated by the negative attention focused on the Tigers. He says that as a self-described "military brat", he still supports the coach.

"If somebody's mad at them for taking a knee, be mad that they gotta bury a teammate from last year.

"Be mad that their coach has to dig in his pocket and spend money to make sure these kids have," he seethes.

"Tell people to stop judging these kids and their coach, and talk to these kids and their coach. Ask them why they're doing what they're doing."

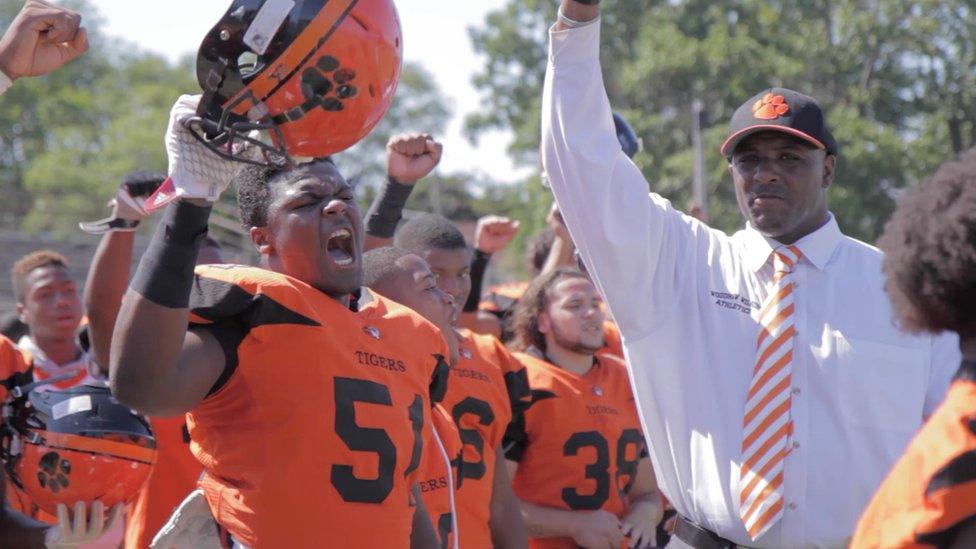

In the Tigers' locker room, the boys gather in their bright orange and black jerseys for a prayer and one last pep talk. The tiny brick room is steamy and sweaty. Anticipation is high. Brown enters in slacks and a crisp white shirt, a Tigers cap and a striped orange tie.

"How you feel?" he asks the room.

"ENTHUSED, SIR," the boys boom back.

"I'll lay my life down for any one of you," he begins. "Any one of you at any moment's time. We understand what the people think about us - that's OK. That's OK because we know what we do."

His voice rises.

"We know the character that's built amongst men in here. We're going to show them on the field today - you understand me?"

"YES, COACH."

"First whistle to the last whistle - Tigers all day. Here we go: Too black!"

"TOO STRONG."

"Too black!"

"TOO STRONG."

"Too black!"

"TOO STRONG."

Out on the field, at noon sharp, a five-person colour guard assembles on the side of the field, holding aloft the American flag. They slowly march out onto the field, stopping at the 50-yard line.

"Please remove your hats as we honour America and those who fight for our freedom," an announcer booms over the loudspeaker, "with the playing of our national anthem."

As the horns begin blaring on a tinny speaker, Brown - who stands a couple paces ahead of the rest of his team as he had the previous Saturday - drops his huge frame down on his left knee.

Behind him, in a kind of orange wave, the players drop down as well. One player places his hand over his heart. Some bow their heads.

Across the field, the Northern Burlington team stands, then as the final bars play, they raise their grey helmets into the air.

Then Brown does something different - he raises his fist in the air. The boys do the same.

The anthem ends, and the boys leap up with a roar of enthusiasm. It's game time.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat, external and Twitter , external