Garbage City: The scavengers making a fortune from other people's rubbish

- Published

Despite the growing intolerance Copts face in Egypt, they are finding great success in the country's recycling business.

It's the sweet, stifling, nose-crinkling scent that hits you first. Mingled with engine fumes and the whiff of hot sand as we burn up the Cairo motorway, it's the stink of damp cardboard and decaying fruit. It's the smell of Garbage City. And for some, it's the smell of success.

Our taxi jolts through the uneven streets, following a lorry wobbling under its load of compacted cardboard boxes.

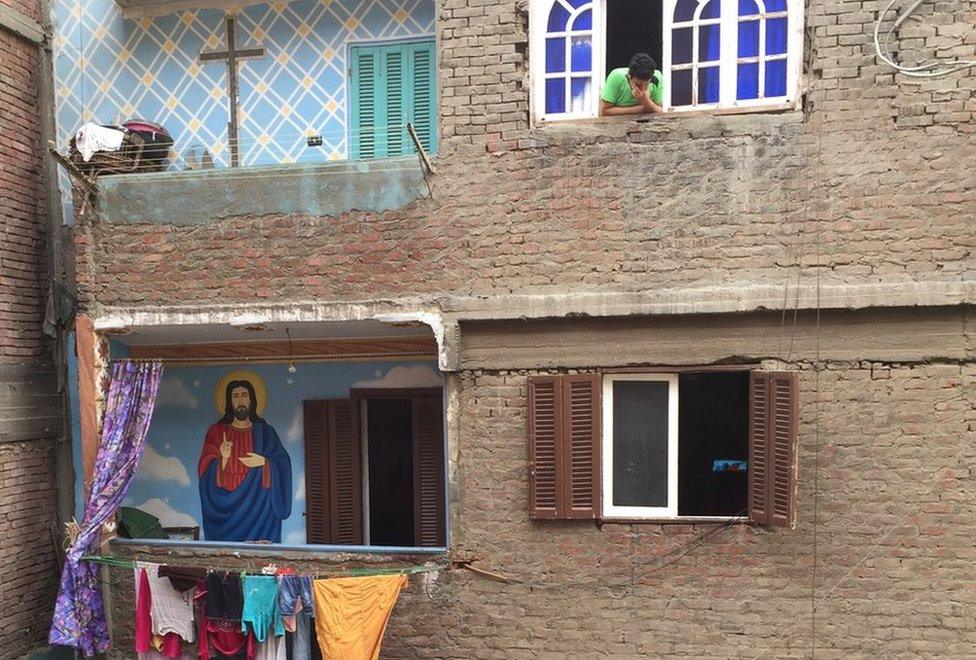

Images of the Virgin Mary, Jesus and the saints, painted two metres high on shop fronts and balconies, look on.

Scraps of plastic bags, foil chocolate-bar wrappers and crumbled newspapers are buffeted by the wind, whipped up and mingled with city dust.

Behind the high walls on the outskirts of Cairo is a mostly Coptic Christian community, known as the Zabaleen - a derogatory term for garbage men.

Settling in an abandoned quarry, they became the informal waste disposal experts of the city in the 70s, collecting rubbish from the capital's streets for free and bringing it back to their homes to recycle it.

Sorting is done by hand - the plastics are separated from the cardboard, the clothes from the organic waste, before they're sold on to the next layer of the community's refuse economy.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

The various materials are pulverised, melted or pelleted, until all that's left over are the rotting vegetables.

Even these are fed to the pigs that are kept in towering apartment blocks - their grunts occasionally echo down from the floors above. Garbage City is one of very few areas in Cairo where you can find pork served on street corners.

Today the streets are empty - it's a Sunday. Up the hill, the Coptic church inside a carved-out cave has a congregation of about 4,000, but this is a sparse turnout compared to high days and holy days, when it can hold up to 20,000 people.

We wander between the long lines of red brick apartment blocks, row after row of balconies decorated with built-in stone crosses.

Shouts bounce off the walls from a children's football game up the street. Small eyes smile at us from behind vast cubes of compacted aluminium, stacked up like hay bales and glistening in the sunshine.

The sun flashes on a piece of smooth metal. Carefully displayed on the street, on picnic rugs, is an array of pans, plates, rugs, champagne flutes, silver cutlery, 10 suitcases, an electric blender, ruffled silk bedsheets and a slow cooker.

But this is not a market stall. None of these items, my guide explains, is for sale.

"This is a bride's new home," he says. "These are her wedding gifts. She leaves them on the street for an afternoon to show all the neighbours how wealthy they are."

Garbage City may not be paved with gold, but it's not without opportunity.

Coptic Christians are a significant minority in Egypt

The Zabaleen are thought to be some of the most efficient recyclers in the world, and as international demand for recycled materials has increased, new businessmen have built their own companies here.

Trappings of individual success are littered around Garbage City - a scattering of smart-suited young men with designer sunglasses and expensive wristwatches.

Some young entrepreneurs have degrees, but not all. Enough education to open a bank account can be all that's needed.

Although legal ownership of land in Garbage City is complicated, it reportedly changes hands for 10,000 Egyptian pounds - about £900 ($1,100) per square metre - a sign of the lucrative business, or speculative property buying on Cairo's outskirts?

We spot Adel's car before we find him - a sporty, bright orange model, gleaming in the dusty streets.

He's only dropping by, he says. He left Garbage City and bought a house in one of Cairo's gated communities - areas with names like Beverly Hills and Hyde Park - but his business is still here.

Opening the shutter to his warehouse, he points out a large wheel of green plastic, as tall as a person.

"I was the first to buy a machine that could create that here," he says. "It turns plastic bottles into strips of industrial binding. It's just one part of my business. Now I take in garbage from across Egypt."

Another machine spits out a perfectly compressed cube of metal, with flashes of faintly recognisable colour from scrunched-up soft drinks cans.

Scaling up his business has worked for Adel.

He now sells his recycled products around the world. His daughter attends a good school in Cairo. He's a member of one of the city's illustrious members' sports clubs.

But it isn't a secure living. International waste contracts rely on stability and consistency, something in short supply in today's Egypt. Socially, he's still in a precarious position.

"I'm not ashamed of being a Zabal," he says, "but…" He shrugs his shoulders, not wanting to offend the city that gave him his success. "But I hope my daughter won't do this."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat, external and Twitter, external