Colombia Farc ceasefire: The man who photographed a little-pictured war

- Published

Colombians are deciding whether to sign up to a ceasefire with the Farc rebel group, and put an end to more than 50 years of war. One photographer - Jesus Abad Colorado Lopez - documented the violence in his images over many years, as his former colleague, the BBC's Juan Carlos Perez Salazar, explains.

Strangely, despite the Colombian war's longevity, there are very few defining images recording it.

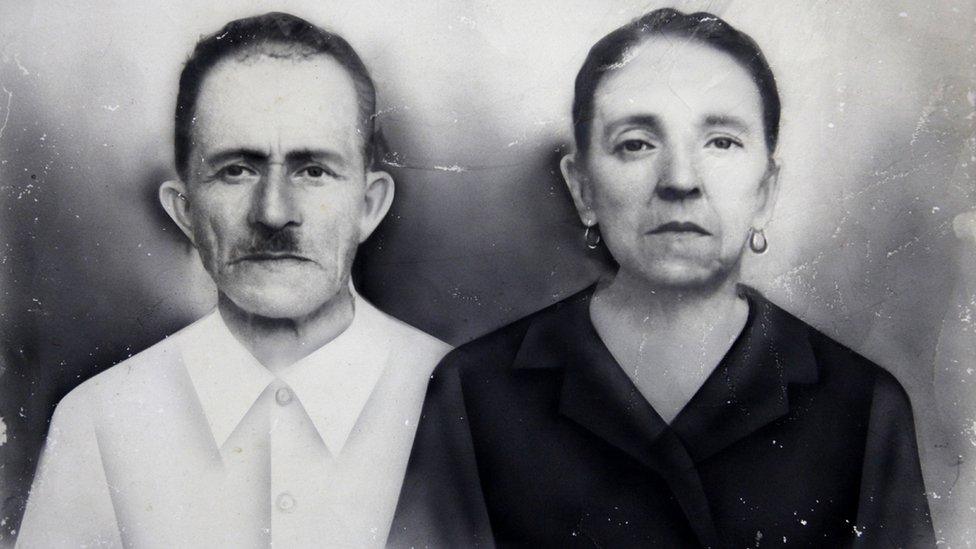

Jesus Abad Colorado Lopez is the photographer who has perhaps best captured the pain of the war over the past 25 years. But this story begins before his birth, with a photo that he didn't take.

In 1960, his grandparents were living with their family in the town of San Carlos, Antioquia, in the middle of Colombia. It was the era that is referred to within the country now simply as La Violencia - The Violence. Sympathisers of the two main political parties - Liberal and Conservative - faced each other in a bloody war.

His grandparents were Liberals in a Conservative town.

One night the mob came into their house, killing the grandfather and slitting the throat of the smallest child - a little boy. The grandmother stopped eating and she died grief-stricken four months later.

The family felt they had to escape to Medellin, the capital of Antioquia. But they hadn't escaped violence and found themselves again living with war from the 1970s through to the 1990s.

In the black and white photograph of Colorado Lopez's grandparents, you can trace the roots of the current violence in Colombia.

The bipartisan struggle that forced out the family was the origin of the Farc and of the war that has consumed Colombia over the past few decades.

More on Colombia from the BBC

Colorado Lopez took the vast majority of his photographs in black and white.

"I think it is more respectful. Colour is too bombastic in violent situations. Black and white gives a more documentary feel, a more sorrowful one."

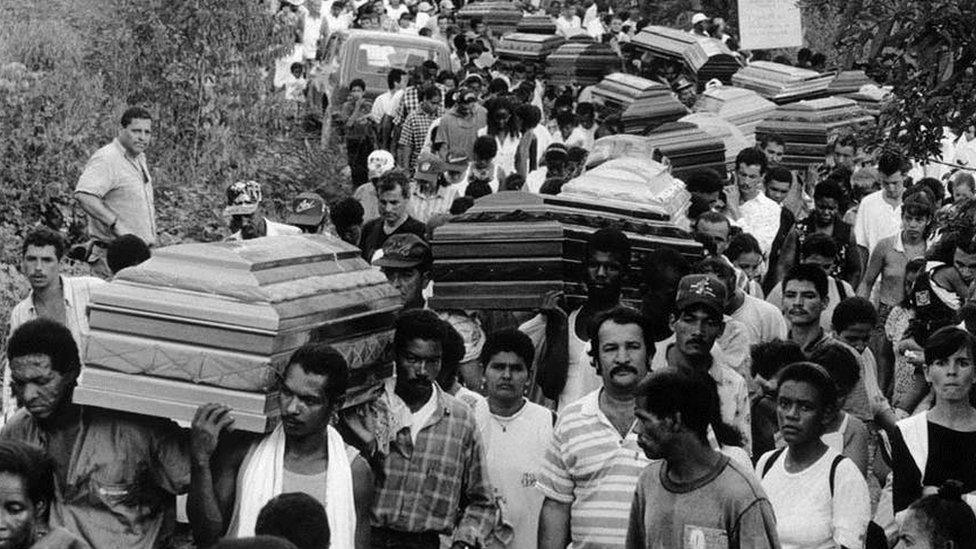

A collective burial of victims of an ELN (National Liberation Army) guerrilla attack on a pipeline in 1998 - 78 people died in the incident

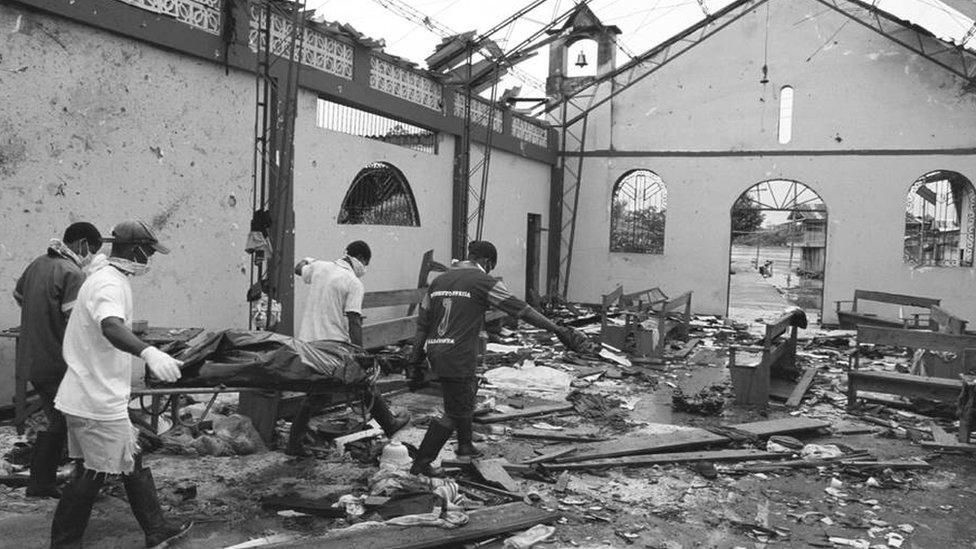

An operation by the Colombian army in response to guerrilla attacks on Jurad Choc in 1999

His black and white images record the horror of war. Often he was the only journalist to have travelled to sites where a massacre had taken place.

And he was almost always the last to leave. It was never so much the bare facts of what led up to the massacre that interested him, but rather the consequences. He wanted to explore the repercussions that follow every violent act, and that transform - or destroy - lives and societies.

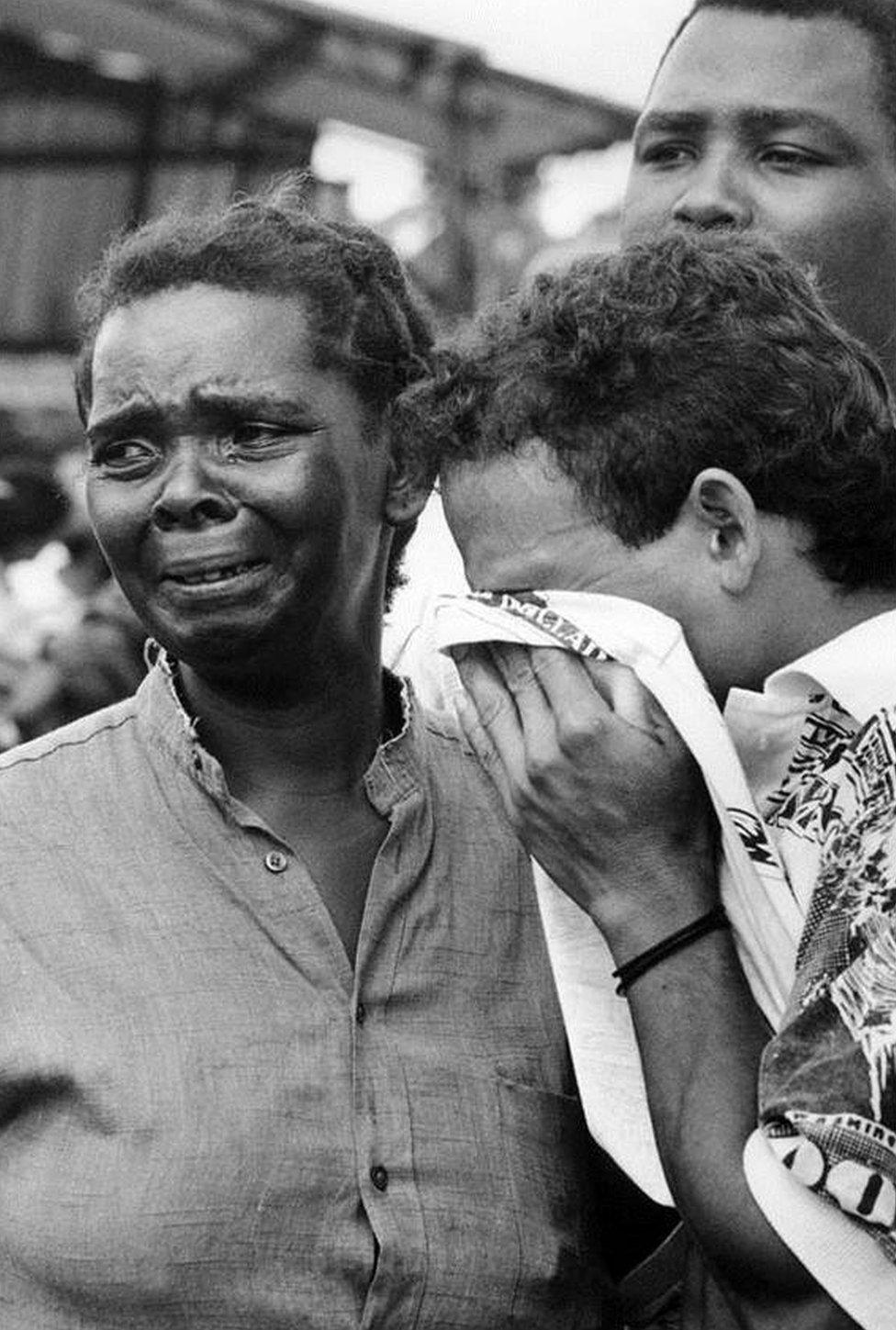

Families of the victims of a guerrilla attack in 1995

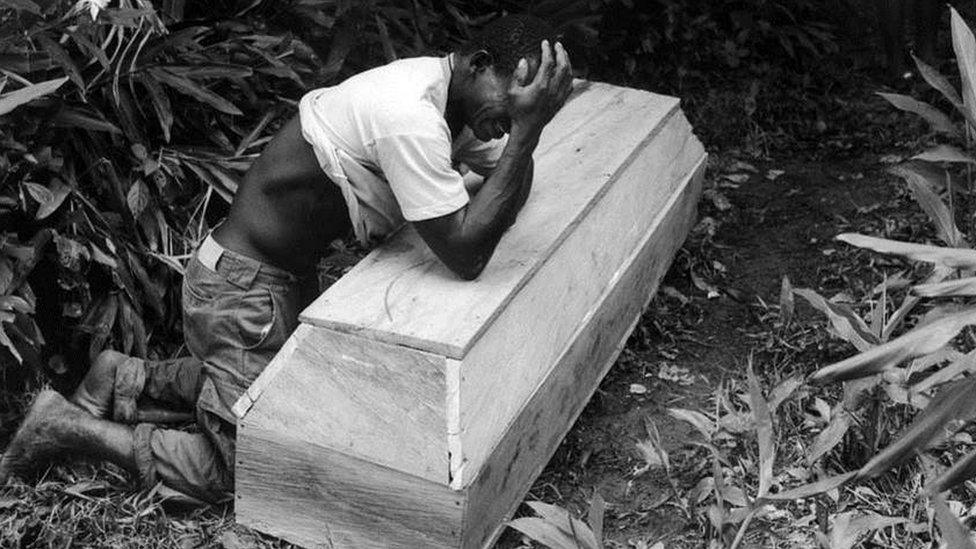

Colorado Lopez has always formed personal connections with people, allowing him to take intimate photos, such as the one of Aniceto, who watched his wife Ubertina bleed to death from a gunshot, while the army and the guerrillas stopped him from taking her to hospital.

When they allowed him to, it was already too late. Colorado Lopez accompanied him as he took her body home again and recorded his profound sorrow.

Aniceto takes the body of his wife Ubertina through the jungle in the region of El Choco

"If I give importance to a human being and he understands my solidarity, surely there is no problem in having this record. It's my duty to memory. I'm a witness," says the photographer.

Victim of a guerrilla attack on a church in Bojaya, Choco, 2002

Colorado Lopez wanted to record the victims. He never exhibited photographs of commanders or generals, or those who held power. He showed only low-ranking fighters and civilians.

And many of those were pictured in difficult circumstances, like the soldier who survived a guerrilla ambush on his convoy in September 1993, while his comrades lie dead around him on the road.

Or this soldier who cries inconsolably because the guerrillas killed his 13-year-old sister. They had previously warned him that if he did not leave the army, they were going to kill his family. His superiors did not believe him when he told them about the threats.

But his camera lens has above all focused on civilians, those who found themselves caught up in the crossfire and who had been the vast majority of the 220,000 violent deaths, external that are estimated to have happened over the past few decades in Colombia.

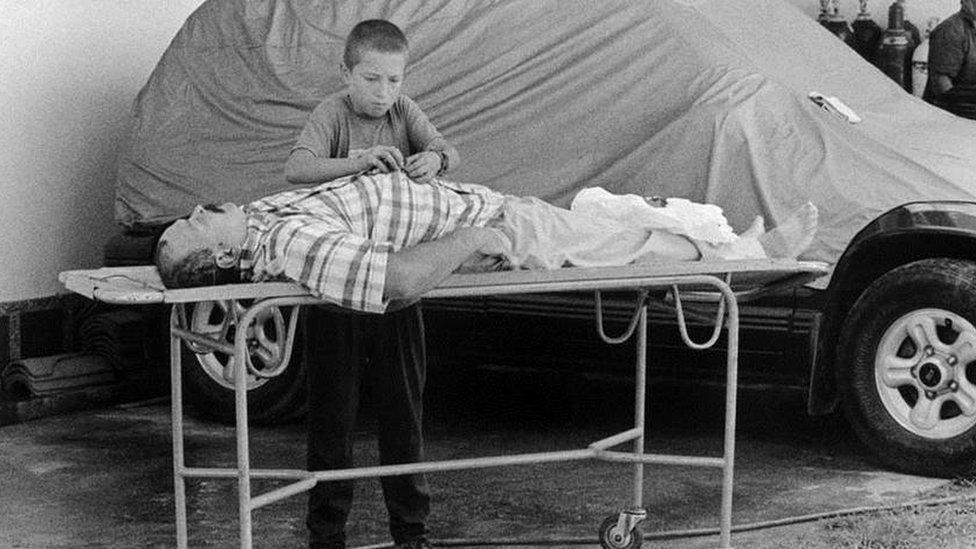

So he managed to capture such incredible images as the boy fastening the shirt of his dead father, killed by paramilitaries in San Carlos in October 1998, the same town that, 38 years previously, Colorado Lopez's family had fled.

Or the initials of the United Self-defence Forces of Colombia, the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), cut with a knife into the arm of a young woman of 18 by paramilitaries who kidnapped and raped her in one of the poor neighbourhoods of Medellin in November 2002.

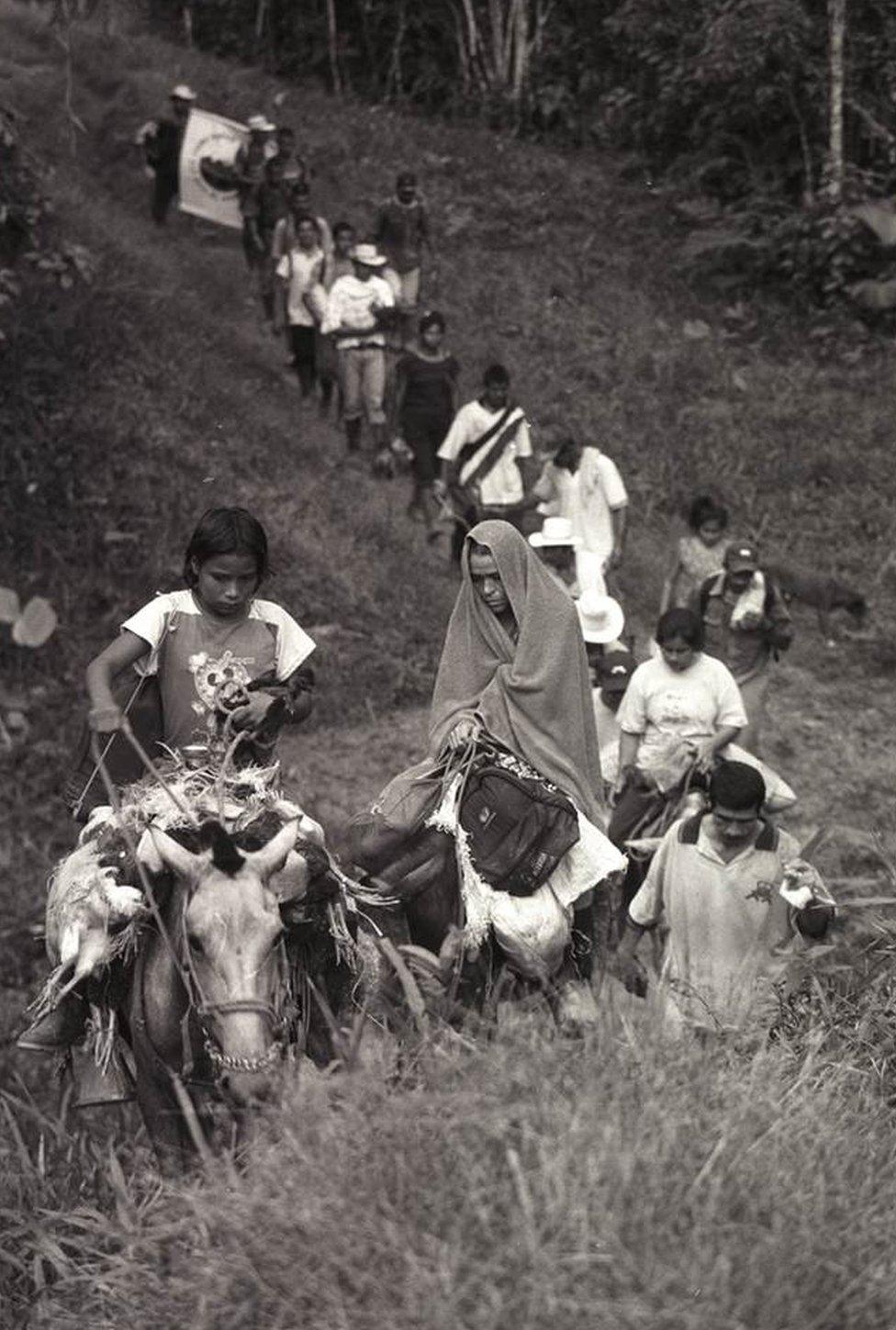

Or this almost biblical image of peasants leaving their village of San Jose de Apartado following a massacre by paramilitaries with the help of the army.

But the wounds of war are to be found not only on bodies. They are also among landscapes and communities.

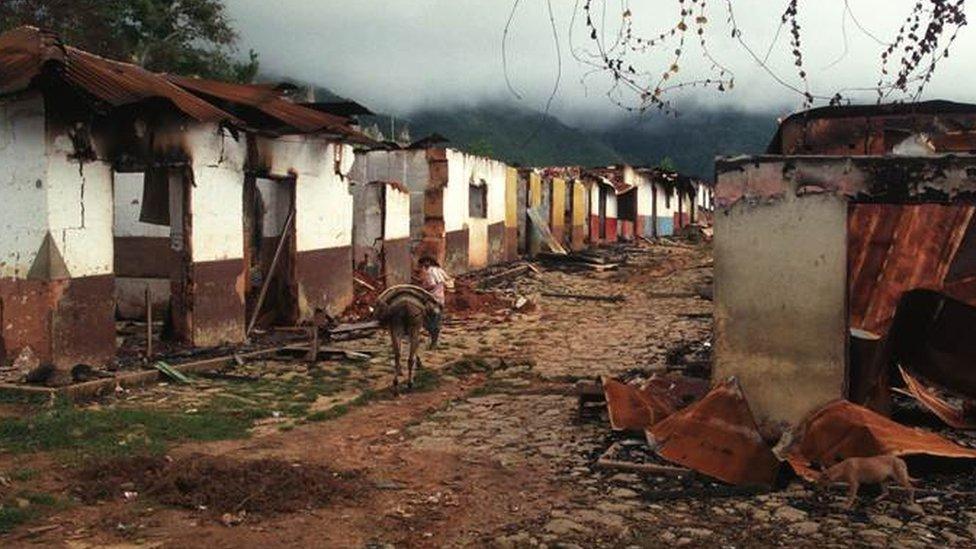

Such as in El Aro, Antioquia, where the paramilitaries - with the complicity of the army - spent five days torturing and killing 15 people in the main square, while they forced the rest of the inhabitants to watch. They then looted and set fire to the town.

When the paramilitaries left, the survivors also left El Aro en masse.

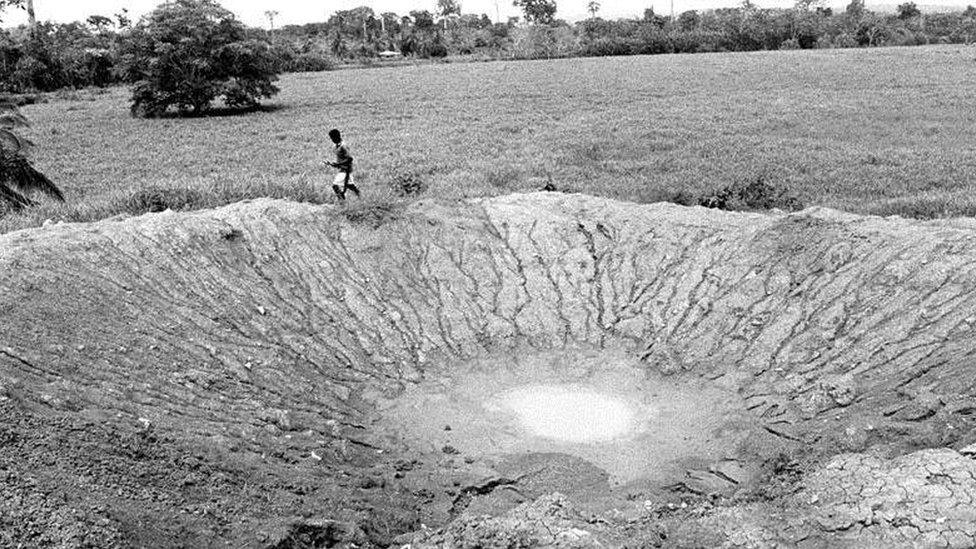

Or the crater left by a bomb fired by the army during an operation against the guerrillas in Rio Sucio, Choco, in which they were accused of acting in conjunction with paramilitaries. The operation left at least 8,000 homeless.

Or the bullet marks in a school that found itself caught in the crossfire.

The menacing presence of war is almost always there in the photographs of "Chucho", as the photographer is known among his friends.

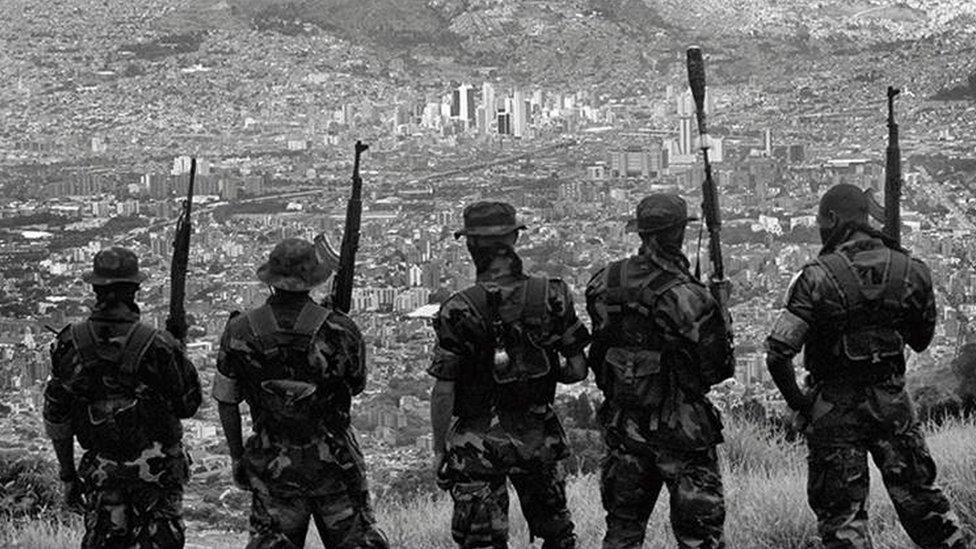

Such as in this photo, in which a group of paramilitaries watch the city of Medellin, the capital of Antioquia, from the mountains above.

Despite the fact that his family has continued to fall victim to the conflict (a cousin was disappeared by the army, another died kidnapped by the Farc) and that he himself has been kidnapped twice by guerrillas, another of his favourite themes is hope in the midst of sorrow.

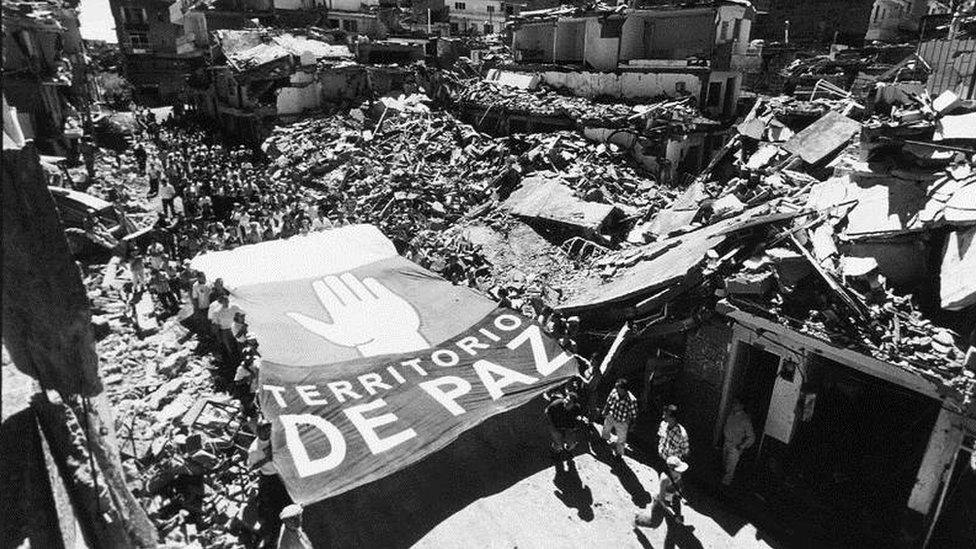

That is the message of this photograph, of a march by the inhabitants of Granada, calling for peace after a guerrilla operation left their town in ruins.

At times they are intimate, not epic photographs, like this butterfly which landed on the ammunition of a paramilitary. He only reluctantly allowed his photo to be taken, as he thought his masculinity was being questioned.

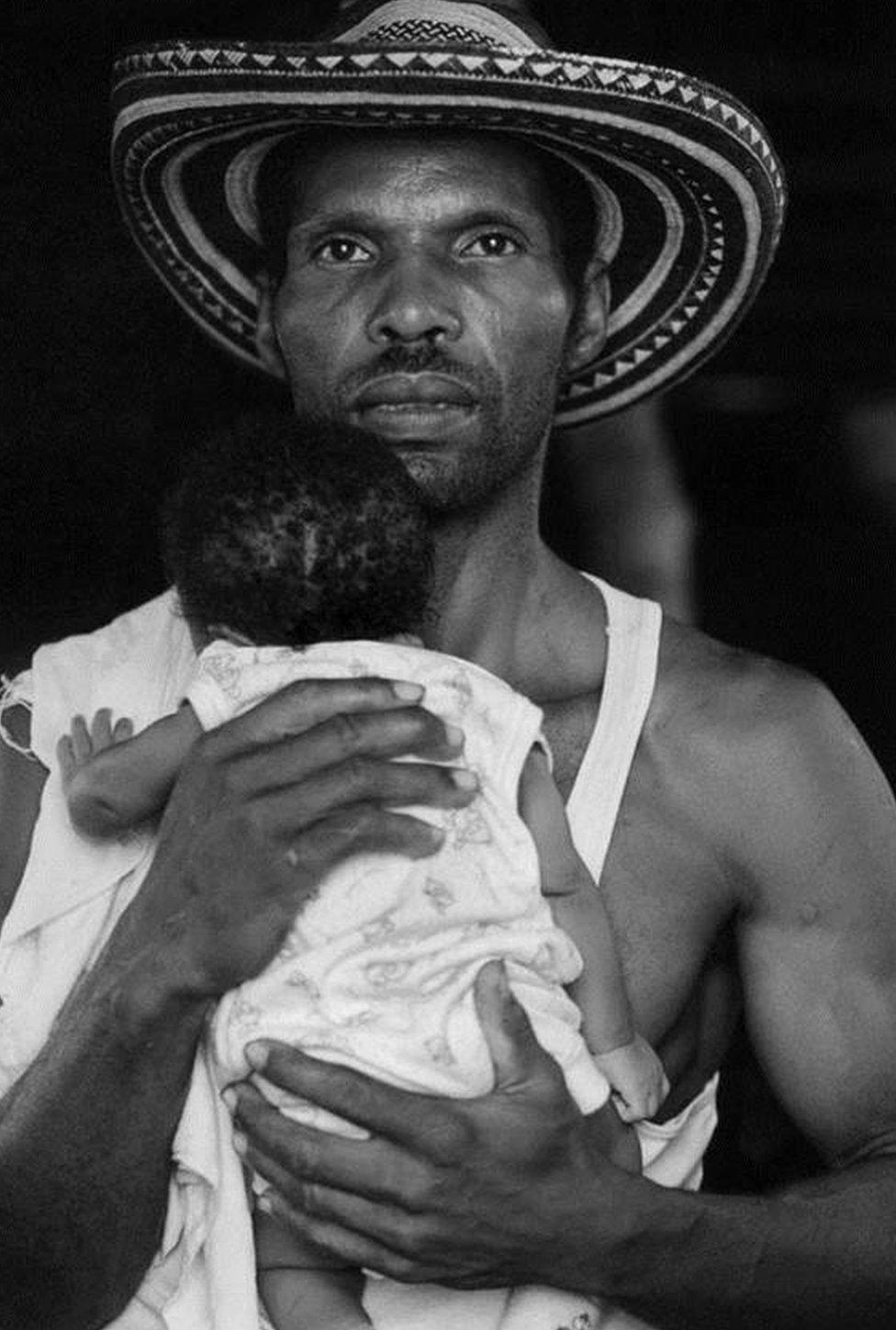

Or the father who returned with his daughter to his home town after being forcibly displaced for several months, while guerrillas and paramilitaries waged a bloody battle.

Or this last photograph, with which we close this story and which, in some way, manages to encapsulate what Jesus Abad Colorado Lopez (referred to in Colombia as the "the witnesses' witness"), tries to achieve in all his work: "Don't forget, remember, mourn and find justice."

And offer hope.

Ana Felicia Velaquez, who returned to the house she had been forced to flee during the war, bringing flowers so the house "would not feel sad"

Jesus Abad Colorado Lopez was born in Medellin, Colombia, and worked for the newspaper El Colombiano between 1992 and 2001. This picture of him was taken by a child who was escaping with his family from a paramilitary attack on their town. He is the author of Mirar De La Vida Profunda (A Gaze At Life Profound).

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.