How maths can get you locked up

- Published

Criminals in the US can be given computer-generated "risk scores" that may affect their sentences. But are the secret algorithms behind them really making justice fairer?

If you've seen the hit Netflix documentary series Making A Murderer, you'll know the US state of Wisconsin has had its problems delivering fair justice.

Now there's another Wisconsin case that's raised questions about how the US justice system works.

In the early hours of Monday 11 February 2013, two shots were fired at a house in La Crosse, a small city in the state.

A witness said the shots came from a car, which police tracked down and chased through the streets of La Crosse until it ended up in a snow bank. The two people inside ran off on foot, but were found and arrested.

One of them was Eric Loomis, who admitted to driving the car but denied involvement in the shooting.

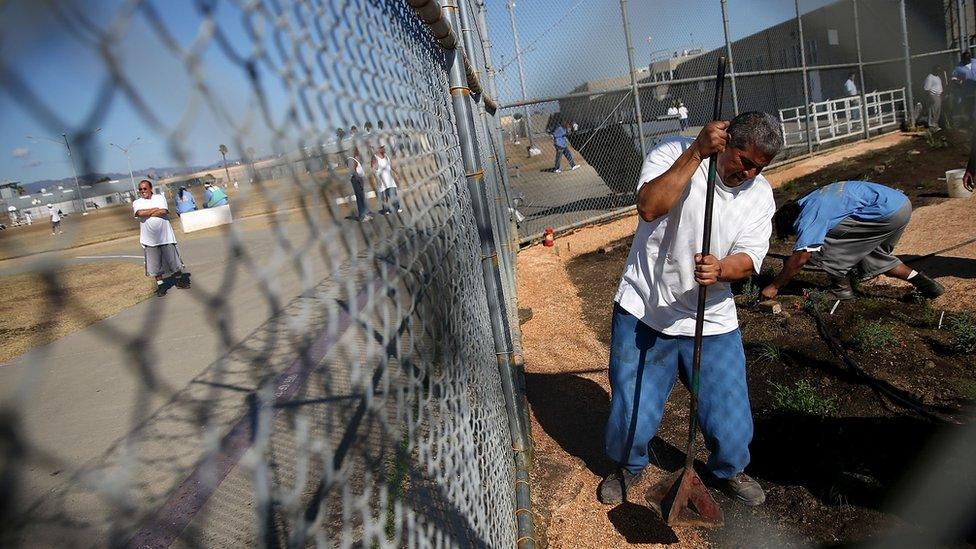

Prisoner Eric Loomis challenged the assessment which led to his incarceration

In court, he was sentenced to six years in prison - and this is where the maths comes in.

In deciding to lock Loomis up, the court noted that he had been identified as an "individual who is at high risk to the community" by something called a Compas assessment.

The acronym - which stands for Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions - is very familiar to Julia Angwin of ProPublica, an independent investigative journalism organisation in the US.

"Compas is basically a questionnaire that is given to criminals when they're arrested," she says. "And they ask a bunch of questions and come up with an assessment of whether you're likely to commit a future crime. And that assessment is given in a score of one to 10."

Angwin says the questions include things like: "Your criminal history, and whether anyone in your family has ever been arrested; whether you live in a crime-ridden neighbourhood; if you have friends who are in a gang; what your work history is; your school history. And then some questions about what is called criminal thinking, so if you agree or disagree with statements like 'it's okay for a hungry person to steal'."

A risk score might be used to decide if someone can be given bail, if they should be sent to prison or given some other kind of sentence, or - once they're in prison - if they should be given parole.

Compas and software like it is used across the US. The thinking is that if you use an algorithm that draws on lots of information about the defendant it will help make decisions less subjective - less liable to human error and bias or racism. For example, the questionnaire doesn't ask about the defendant's race, so that in theory means no decisions influenced by racism.

But how the algorithm gets from the answers to the score out of 10 is kept secret.

"We don't really know how the score is created out of those questions because the algorithm itself is proprietary," says Angwin. "It's a trade secret. The company doesn't share it."

And she says that makes it difficult for a defendant to dispute their risk score: "How do you go in and say I'm really an eight or I'm a seven when you can't really tell how it was calculated?"

It was partly on that basis that Loomis challenged the use of the Compas risk score in his sentencing. But in July the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that if Compas is used properly, it doesn't violate a defendant's rights.

Bad news for Eric Loomis. However, the court also ruled that future use of the risk score should come with a health warning explaining its limitations - for example, that the algorithm behind it is kept secret and that the risk score is based on how people with certain traits tend to behave in general, rather than on the particular person being considered.

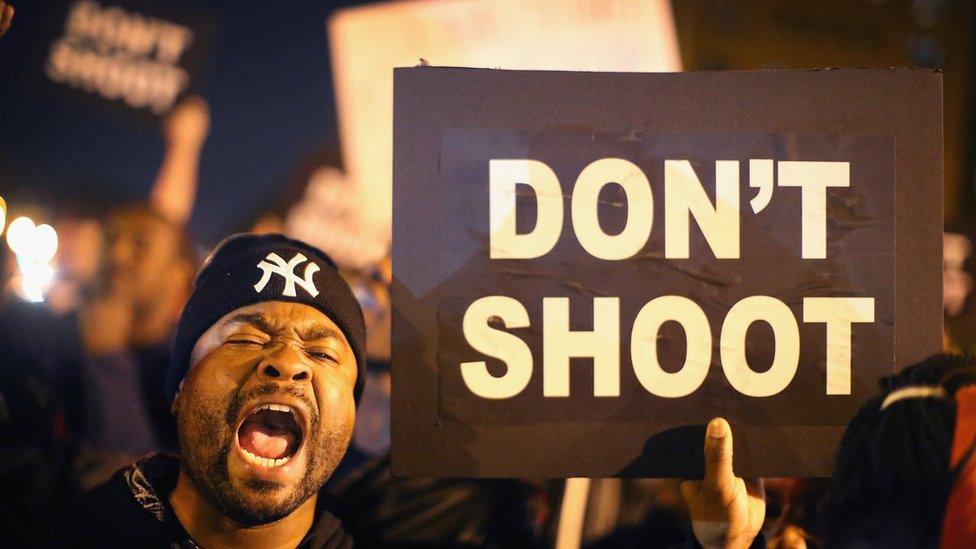

The Wisconsin Supreme Court also warned that Compas may give ethnic-minority offenders disproportionately high risk scores - a pretty serious weakness if true, especially given current tensions around policing and race in the US.

The court based this concern partly on an investigation by Angwin and her colleagues at ProPublica, external into how accurate Compas scores turned out to be in practice. They looked at the risk scores of 7,000 people arrested in one area of Florida over two years and came up with a shocking finding.

"If you look at a black and a white defendant who have the same history, they're both the same age, the same gender, same criminal history and same future history - meaning after they were scored they either went on to do four crimes or two crimes or no crimes, the black defendant is 45% more likely to get a high risk score than the white defendant," says Angwin.

Does Compas risk heightening tensions between police and the black community in the US?

How could the algorithm throw-up racially-biased results if it never asks about race? Angwin says: "The algorithm asks a lot of questions that can be considered proxies for race."

For instance: Has anyone in your family been arrested? How many times have you been arrested?

"These types of things, we know because there's so much over-policing of minority communities, are more likely to be true for minorities than for whites."

ProPublica's findings - unsurprisingly - have generated lots of debate in the US about the use of risk scores.

Some have disputed ProPublica's analysis. The company behind Compas issued a detailed response, external in which it unequivocally rejected ProPublica's conclusion that the algorithm results in racial bias.

And three researchers unconnected to Compas have also written a draft paper, external questioning ProPublica's methods. The lead author was Anthony Flores, an assistant professor in the criminal justice department at California State University, Bakersfield.

He says algorithms are proven to be better predictors of reoffending than judges and that ProPublica misinterpreted what the data showed.

"We found no bias of any kind when we re-analysed their data," Flores says. He argues ProPublica is guilty of "data torturing" - essentially trying lots of different ways to measure something until they got the finding they wanted. "We didn't necessarily disagree with their findings, we just disagreed with their conclusion."

The BBC spoke to a number of statisticians who aren't involved in the row and they broadly agree there are other - arguably more logical - ways of looking at the same data that don't suggest racial bias.

Find out more

More or Less is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service

Download the More or Less podcast

More stories from More or Less

But all sides in this statistical showdown do seem to agree on one thing. If black people in general are more likely to reoffend, then a black defendant is more likely to be given a higher risk score.

So while the algorithm itself may not be racially biased, it is reflecting racial biases in the criminal justice system and society more widely.

Angwin says that's something that deserves deep thought.

"If we're talking about people's freedom, then we have an obligation to get it right," she says.

"I think it's really important to remember that we're looking at math, which is very adjustable. And so we could change it to make sure that it has the outcomes we want it to have.

"Do we want to over-penalise black defendants for living in poor neighbourhoods and having what look like to this algorithm higher risk attributes, despite the fact that they themselves might not be risky people? Or are we willing to live with that over-scoring because we think it gives everyone this sense of fair treatment?"

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.