Fighting back in the name of Dwayne

- Published

As a church minister, Lorraine Jones was used to helping those affected by the violence on the Angell Town housing estate in Brixton, London. But two years ago she suffered her own loss when her son, Dwayne Simpson, was stabbed to death in the street. Here she talks about how, after the tragedy, she felt compelled to continue a boxing club he had begun to keep young people out of gangs.

We're talking about gang warfare. There's a huge amount of knife crime - we have boys with scars from their ears to their mouth - but what's escalating now is gun crime. Some even wear bulletproof vests.

These young people are broken. They're abused, they're groomed into delivering drugs, some as young as nine. They're lured into that life with the promise of money. Poverty and lack of education is at the root of it, and that's what makes it so hard for them to change, because what job are they going to get that's going to bring in a good income? And who is going to help them get on to the employment ladder?

Once they're involved, they're exposed to violent crime at every level - with both girls and boys being sexually abused and raped. I worked with one young lady of about 18. A group of young boys went to her home to find her brother. He wasn't there and she was gang-raped.

This is what is happening in our community. It's horrific.

The other day I was called to the home of an elderly woman who had raised her grandson after her daughter died in childbirth. He was 26, and had special needs. She got a call from the police to say that he had been found dead on the streets, 10 minutes from home. He was attacked by a group of boys and kicked in the head. She had thought he would bury her. Now she has to bury him.

These are the kind of families that I'm working with on Angell Town estate and beyond. I've been doing this for 20 years now - everybody knows me here. They call me Mum.

Despite all this, I didn't realise my own children were also at risk. I learned the hard way and now I've lost my son.

Dwayne was a caring boy, very soft-hearted. I remember when his goldfish died, we had to bury it in the garden and conduct a ceremony. Growing up, he loved drama, dancing, comedy and sport, and was popular with his teachers. But when I divorced his father the family broke down. It really broke Dwayne's heart. It was a devastating period of my life, I remarried and had another child but I went through a devastating second divorce and was left to bring up seven children on my own.

Dwayne got quite depressed and his teachers told me he had trouble concentrating. Then he started truanting. One afternoon I got a call to say he was not in school and then, to my horror, the police rang to say he had been arrested. Dwayne had been caught acting as look-out boy for a robbery with some older boys from Lambeth. He was sentenced to more than two years, a harsh sentence for a first offence. He was only 15.

He was sent away before he could finish school but he did lots of different courses while he was in prison. I still have all his certificates. He also became a mentor to other prisoners. But he experienced a lot of harsh treatment and he saw the impact prison had on young people in terms of emotional and mental breakdowns.

When I'd visit him in prison he always came out with a big smile on his face - he's like me in that respect, we smile through our pain.

He would tell me: "Mum, I'm not going to come back in here. It's a horrifying place. I'm never going back."

When he came out, he told others about his experience to deter them from that path. Some people brag about going to prison and use it as a stripe on their shoulder. They make out that prison's "easy" - but Dwayne would tell them it wasn't.

He used to come home in tears, because he had a heavy burden. "Mum, there's nothing for the young people to do here," he'd tell me. "Where are they supposed to go? They're just sitting on walls and being harassed by the police."

Dwayne experienced this too, being taken in the police van, being roughed up and then released without any papers to say why he'd been searched.

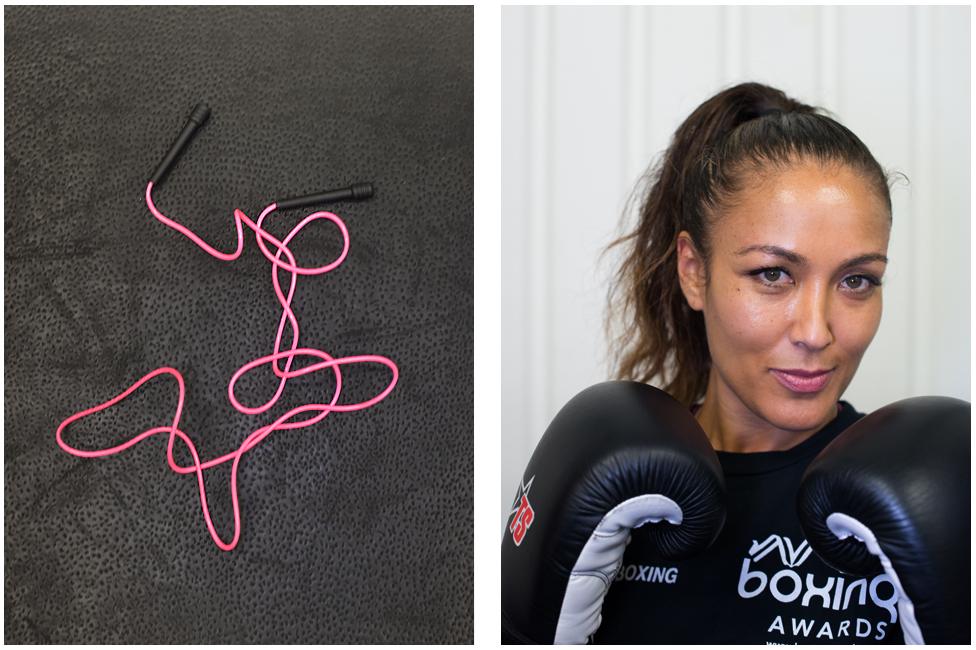

Mary Chinyerek runs Angell Delight, an empty shop unit on the estate where Dwayne ran boxing sessions

Get the Outlook podcast for more extraordinary real-life stories

Our house had become a target for police because of Dwayne's criminal record - and because my eldest son had gone off the rails, too. We were raided every month, it was just how it was. Their tactic was to raid our home in the early hours in the morning, when everyone was still asleep. They always came with about 10 police officers, sometimes with dogs. They would be looking for mobile phones, laptops, drugs. Each time they left with nothing, but then after all that upheaval I'd have to get the kids to school and myself to work - can you imagine? It was unbearable. So I knew how other families in Angell Town were feeling.

There was no safe space on our estate for young people to hang out, nowhere for them to go, nothing to do. The level of violence was unbelievable. Dwayne told me he was determined to do something to change things. "I can't just sit here, because to be honest, the way things are, I don't know if I'll reach my 21st birthday," he told me.

And he didn't.

Dwayne loved boxing and circuit training, so he decided to set up a club to train young people. They mainly worked out in local parks, but then he got permission to use an indoor space on the estate called Angell Delight - an empty shop unit run by a volunteer from the estate, Mary Chinyerek. It was really too small for boxing and there was no equipment, but at least it was dry. Mary says Dwayne was the first young person who had ever asked to use it.

Soon Dwayne had gathered together about 30 young people. By giving them something to take pride in, he was keeping them out of the clutches of gangs.

About a year after Dwayne had started the club, just a few weeks before his 21st birthday, I came home from work to find the shopping was not done. I dropped my briefcase and said I was popping out to the shops. "OK Mum, that's fine," Dwayne said. They were the last words my son ever spoke to me.

Forty-five minutes later, while I was unpacking the shopping, two young people knocked on the door - I knew them from Dwayne's boxing sessions. They said: "Mum, Mum, Dwayne's been stabbed."

I said: "Is it serious?"

They said: "Yes, Mum."

I said: "Do I need my car?"

They said: "No, Mum. It's just over there." Pointing, frantically.

I grabbed my mobile phone and ran across the park. I saw my son lying on the street with the paramedics around him. They had opened his chest right there in the street to try to stem the bleeding. Dwayne had been stabbed in the chest, and the knife had gone right through to the other side.

Later, I saw exactly what happened to Dwayne - it was all on CCTV. The footage showed a teenage boy walking along Brixton Road when the attacker started chasing him with a huge knife. Dwayne was driving past with my brother, and saw them run into a side road. "Uncle, this boy looks like he's in trouble," Dwayne said. My brother told him to leave it but Dwayne could see it was serious and jumped out of the car. He grabbed a steering lock, to knock the knife out of his hands. The boy got away, but then the attacker turned on Dwayne out of frustration - and stabbed him straight through the heart.

They brought him to King's College Hospital, just a few minutes away. He was on a life support machine for two days. I was by his side throughout. His face and his body were so swollen I could barely recognise him. His organs had packed up - a machine was keeping him alive. He was covered in blood from emergency surgery on the clots in his chest. The only places I could kiss Dwayne were his forehead and his feet. And because I was kissing him the blood was all over my hair. I just loved him through that time, this was my son.

I said: "Son, you said to me that you don't think you're going to make your 21st birthday but I want you to know that I am with you. And Jesus is with you on this journey."

The instructors

Boxing instructor Richard Davis was the first to come on board - he and Lorraine share a grandchild

Det Supt Sean Oxley found a home for Dwaynamics in a disused railway arch near the estate

Boxing helped Michelle Killington cope with the grief of losing her mother - now she's an instructor

PC Alan Douglas-Smith volunteers as an instructor - his brother, Johnny Nelson, was once a professional boxer

Over those two days more than 500 people came to the hospital to see him. There were visits from the police, councillors, church ministers and so many other people that I didn't even know. Elderly people from the estate brought flowers and told me how he had helped them with their shopping, or spoken to their grandchildren when they played up. I had no idea that he was making such a big impact in the community.

Everyone was praying that he would survive, but I knew he wouldn't. When he died, hundreds of people gathered outside our home in the Angell Town estate. All that energy helped to lift me up as a mother. At a moment of great need I was swarmed with love and support.

At the time it was portrayed as yet another gang killing, but this wasn't the case. The judge said it was very unfortunate - it was clear that Dwayne had tried to help and as a result, he lost his life. He died as a peacekeeper, and the courts recognised this.

The man was sentenced to manslaughter. It wasn't murder because he didn't plan to kill my son, he had no dealings with Dwayne. But he got the maximum penalty.

I attended the trial at the Old Bailey twice. The first time was at the beginning, and the second time was when the killer took the stand. He looked like a vulnerable young man. I found out about the environment he grew up in: violence, drugs. He had been in prison repeatedly. And when I saw him I had compassion. I forgave him, because the pain of losing my son outweighed everything else. I prayed and asked God to change this man so he wouldn't kill another soul.

About a month after Dwayne died, a group of boys from his boxing club came to my house - about 30 of them. They said: "Mum, what are we going to do? Dwayne is gone, but we need this club." I told them I couldn't help. I was lost in grief, it was too soon. But they came back again and again and eventually I gave in. My son had died trying to save a life, and I felt compelled to continue his work.

But how? I'm no boxer. As luck would have it though, I knew someone who was: the father of my daughter's partner, Richard Davis, is a professional boxing coach. He came on board.

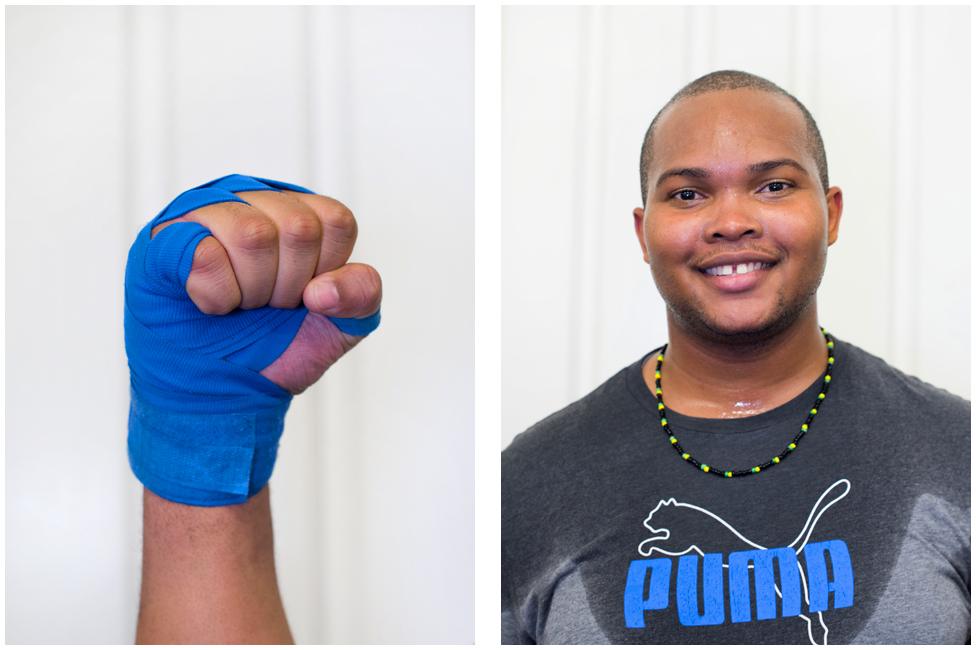

The boxers

Mustafa, 15, was told about Dwaynamics by his teacher - he would like to become a professional

Regan, 8, has made new friends at the boxing club

Andre, from Croydon, only started boxing recently but has built up a good relationship with his trainer

Then I had an unexpected visitor - the police commander for the borough, Richard Wood, came to my home to offer his condolences. He was so warm, and he said the police would support me if I wanted to carry on with Dwayne's boxing project.

Angell Delight, the space Dwayne had been using on the estate, was too small, and our bid to rent a bigger shop unit failed. But then a team of police officers found a space we could use - a disused railway arch, not far from the Angell Town estate. Everyone chipped in for boxing bags and equipment. Then the police went one step further and offered to help with the training. Now every week a group of police officers box with our young people and mentor them.

I've learned that boxing is very technical. It helps you to build discipline. There's no violence, it's all non-contact boxing. It's a good tool to relieve stress and anxiety, which many of these young people suffer from - without support they can develop mental health problems, which can lead to substance misuse. That's when they can start getting into crime to support their habits. If we can help young people find stability and build themselves up, then they can fulfil their potential.

Dwayne had been helping about 30 people - now we work with 300, of all ages: mothers, children and young people. We also run job fairs and mentoring schemes and we've helped young people find work and training.

A handful of parents complain about the fact we've moved off the estate, no matter how many times I explain that it's just not practical to hold sessions at Angell Delight. Some young people from Angell Town don't come because of the postcode wars which we still have to deal with - our area is divided up by gangs and it can be dangerous for young people to cross into another territory.

One young boy from our estate was stopped on his way to Dwaynamics by a group of boys, and after that he didn't come back. His mother and I offered to pick him up and bring him, but unfortunately it didn't work out. Last I heard, he'd got into some serious trouble around gangs.

It's about encouraging young people to make that first step and push back on that barrier of fear. We're offering to help them out of that cycle. It's not something that can happen overnight, but we're persistent.

Of Dwayne's original group of 30 a few are still involved with us. Sadly, some of them are now in prison, or dead.

I visit prisons as part of my ministry, and I was surprised to find word had got around about Dwaynamics. Some prisoners send me poems and pictures and messages of encouragement: "Mum, keep doing what you're doing. When we come out we'll help."

It's a miracle to see young people training with the police now, because it was very hostile before. The mind-set of the community has changed more positively - they're more understanding about stop and search and due to the rise in knife attacks they're engaging with the police, and it all happened through Dwaynamics.

Det Supt Sean Oxley, who works with us, told me that the greatest thing for him was when he came to the arch and saw a young boy who's known to the police. They looked at each other and didn't say a word, but a few weeks later, the boy went up to him and shook his hand.

Recently I heard another story that made me proud. One of our young women greeted a police officer during the Black Lives Matter demonstration in Brixton. A man turned to her and said: "What are you doing, you're siding with the enemy, the police are the enemy!" But she said: "No they're not, they're training and boxing with our youth! Don't you know what they are doing with Dwaynamics?" And the guy shut up. I was just like: "Wow."

The tragedy is that if that boy had run into Brixton police station, instead of away from it, Dwayne might be alive today. We have to work together to stop our kids being killed. It's very easy to abandon hope. But there is hope, and there is evidence of it in my life.

Photographs by Emma Lynch. Production by Vibeke Venema

Listen to Lorraine Jones speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.