When Joni Mitchell wore blackface for Halloween

- Published

The singer Joni Mitchell startled her friends by appearing at a Halloween party 40 years ago disguised as a black man in pimp-like garb. It would be unacceptable today but times were different then, her friends argue. Others disagree. Whichever view you take, her black alter ego was a reflection of her intense identification with black music, writes Kris Griffiths.

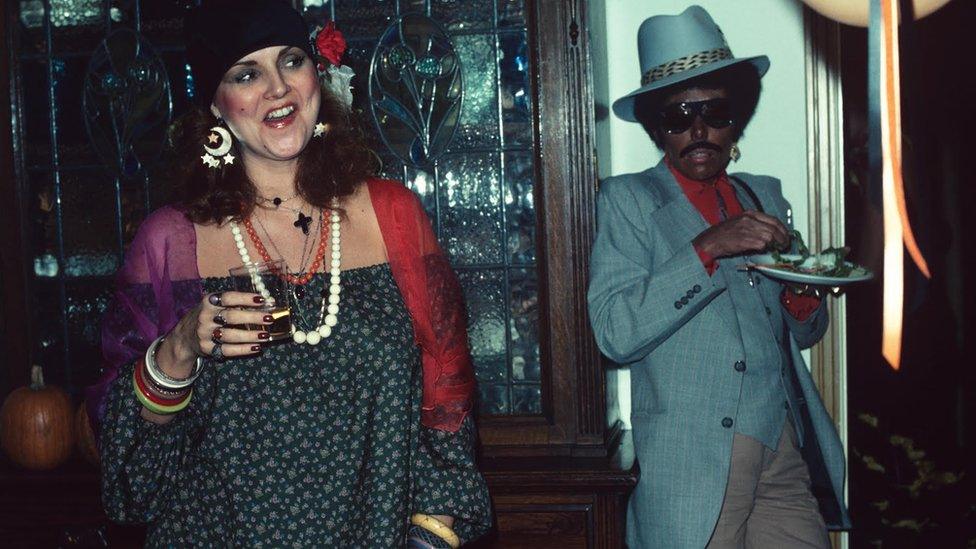

It's Halloween 1976, and eminent session bassist Leland Sklar is throwing a fancy dress party at his Los Angeles home for fellow musicians and record industry types, including producer Peter Asher and drummer Russ Kunkel, who would later appear in This Is Spinal Tap.

However there's one lone guest loitering in the background, whom no-one seems to know, everyone thinking he's someone else's friend - a svelte black man in a zoot suit with matching chapeau, meticulous afro, wide moustache and big, dark shades.

While everyone has brought wives and partners, this pimp-like character has slunk in unaccompanied without introducing himself, and appears content to observe proceedings quietly from the corner after helping himself to the buffet.

Rock photographer Henry Diltz, more used to shooting the likes of Hendrix and Zappa, inadvertently captures the besuited wallflower on film, while snapping his own gypsy-costumed wife. The gatecrasher looks startled in the light of his flash.

Not long afterwards the host, Sklar - still oblivious to this guest's identity despite asking around - finally approaches and asks if he's at the right party.

Only then, does the interloper remove his sunglasses and wig, revealing his true identity: It's Joni Mitchell, world-famous folk music star, a week away from her 33rd birthday.

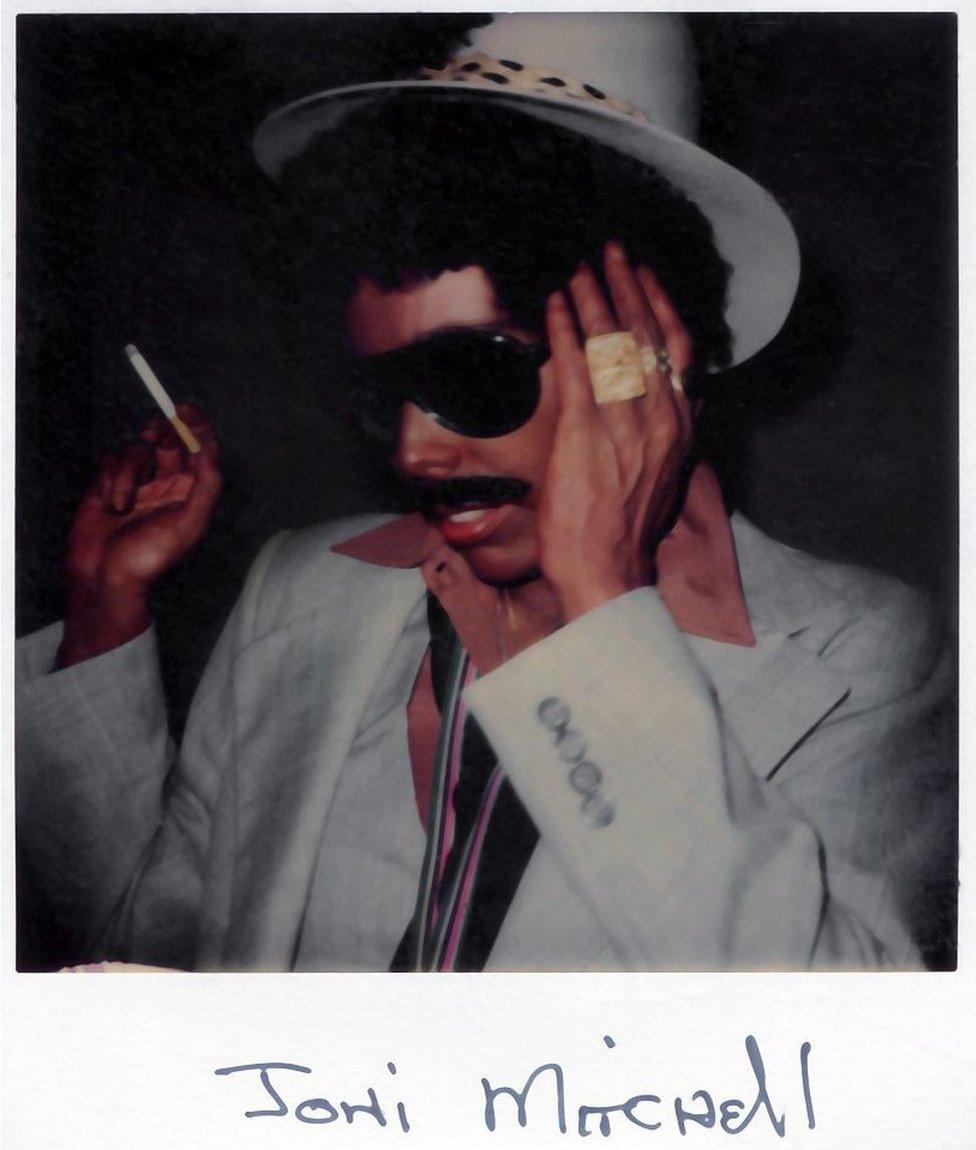

Mitchell posing in blackface in 1977

What makes the discovery even more shocking is that not only is everyone there a friend or acquaintance, many of them have played on her albums, while one, JD Souther, is an ex-lover. None of them had seen through the disguise.

"She dressed up like that to see if she could fool her friends and boy, did she," says Diltz. "Everyone in that room was her friend and none of us got it. She was proud that she could pull that off."

"She stayed in character for most of the evening," continues Sklar. "She's an amazingly gifted artist and it came through in this persona. We laughed about it over the years."

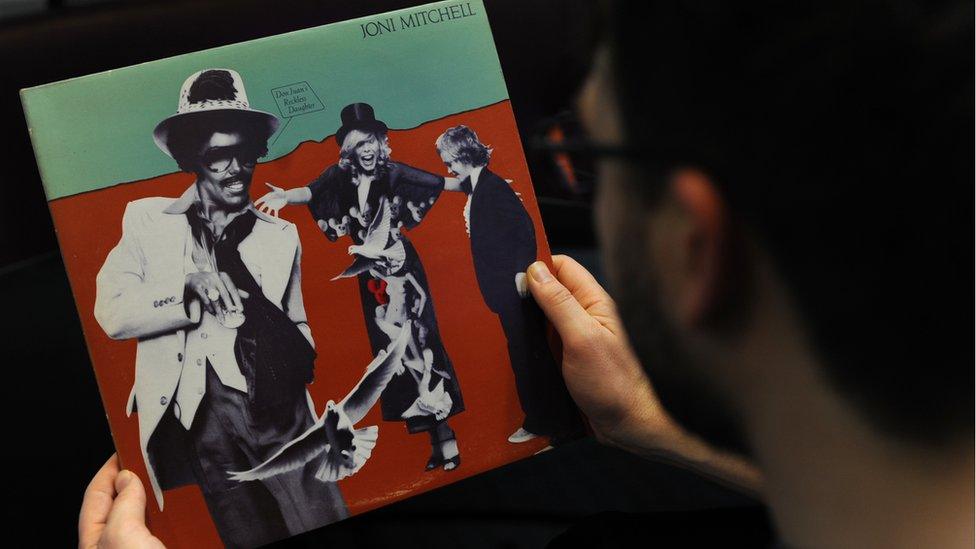

Joni's alter-ego, who she christened "Art Nouveau", would appear on the cover of her next album, Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, released in 1977, and she would intermittently slip into this guise over the next few years. To this day, many record-owners have no idea that the strutting black dandy on that sleeve is Joni herself.

Forty years later, she remains one of the most acclaimed artists of the last half century, a former Toronto street busker turned voice of a generation, combining inventive melodies and chords with poetic lyrics. She ranks alongside compatriots Neil Young and Leonard Cohen as a virtuoso songwriter, and is cited as a significant influence by artists including Kate Bush, Elvis Costello and the late Prince.

So why had Joni, with the world at her feet, chosen this particular, highly questionable, blackface guise?

A decade or so later she put it down to a chance encounter that occurred when she was out costume-shopping for the party.

"I was walking down Hollywood Boulevard (when) a black guy walked by me with a diddy-bop kind of step, and said in the most wonderful way, 'Lookin' good, sister, lookin' gooood'," she told Q Magazine in 1988.

"His spirit was infectious and I thought, I'll go as him. I bought the make-up, the wig… sleazy hat and a sleazy suit and that night I went to a Halloween party and nobody knew it was me."

From People's Parties by Joni Mitchell (1972)

I told you when I met you

I was crazy

Cry for us all beauty

Cry for Eddie in the corner

Thinking he's nobody

And Jack behind his joker

And stone-cold Grace behind her fan

And me in my frightened silence

Thinking I don't understand

But this glosses over how deeply Mitchell identified with black musicians and songwriters - to the extent that some viewed her as being a black man trapped in a white woman's body.

"I don't have the soul of a white woman," she once told LA Weekly. "I write like a black poet. I frequently write from a black perspective."

This may have been a response to being pigeonholed by her gender and spotless image, encapsulated by Melody Maker's 1974 description of her as "elusive, virginal… White Goddess of mythology".

Mitchell was "located in a genre that was seen as - if not racially white - then certainly light, trivial, and feminine" Miles Parks-Grier, a professor at the City University of New York wrote in 2012.

This was not good for her professional prospects. Even worse, he says, "folk was no longer seen as marketable" in the mid-1970s.

Mitchell (pictured in 1968) as she is more likely to be recognised

This is arguably what drove Joni into what fans call her jazz-period, in which she expressed her affinity with what she called "black classical music".

"The black press gets it. I'm not a folk musician," Mitchell told CBC in 2000. "I'm much more related to Miles Davis."

It was while making Don Juan's Reckless Daughter that she met Don Alias, the black jazz percussionist who would become her long-term lover and who later expressed concern that he might be equated with the pimp on the cover, a black man exploiting the desirable white Joni.

Not long afterwards the illustrious jazz composer Charles Mingus invited her to collaborate on what would be his final musical project before he died in 1979, the album titled Mingus. "He thought I had a lot of nerve to be dressed-up like a black dude on the cover," Mitchell recalled. "He was sort of thrilled by it."

"Joni romanticised being black, without the disadvantages," writes Sheila Weller in her 2009 book, Girls Like Us. "She would increasingly insist that her music was 'black' and that, as it progressed deeply into jazz, it should be played on black stations (it rarely was)."

But if she failed to win acceptance as a "black" musician her bold drag-act statement appears to have raised few eyebrows in the era of the androgynous Bowie and Rocky Horror. Today, on the other hand, blackface is as provocative an issue as ever.

American historian Ken Padgett, author of black-face.com, denounces Mitchell's perpetuation of a damaging black stereotype.

"Even in 1976 this Zip Coon caricature was outrageous and offensive," he says. "One wonders how Joni could be friends with legends like [Herbie] Hancock and Mingus, and no-one told her what she was doing was insulting."

Kevin Hylton, professor of equality and diversity at Leeds Beckett University, also takes a dim view of Mitchell's "blackface appropriation" - one he sees as "reflective of her own privilege and limited racial politics".

"Regardless of Joni's raison d'etre," he adds, "no performance of blackface can be neutral in terms of its felt impact on black and minoritised ethnic communities."

A final word on the context from the photographer whose shot gives us the first glimpse of Art Nouveau.

"It was art," says Diltz.

"If someone did that at a party today, I'm sure people would be aghast. But back then was a time of peace and love, when things weren't so analysed.

"She wasn't demeaning black people, but celebrating them."

These days Joni Mitchell is unwell, and she declined to comment for this article except to reassert her often-repeated desire to begin her autobiography, should it ever appear: "I was the only black man at the party."

So maybe the photograph captures an important moment for the legendary singer - the night she came closest to becoming the black jazz musician she always wanted to be.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat, external and Twitter , external