Children's names: Why rich parents set the trend, not celebrities

- Published

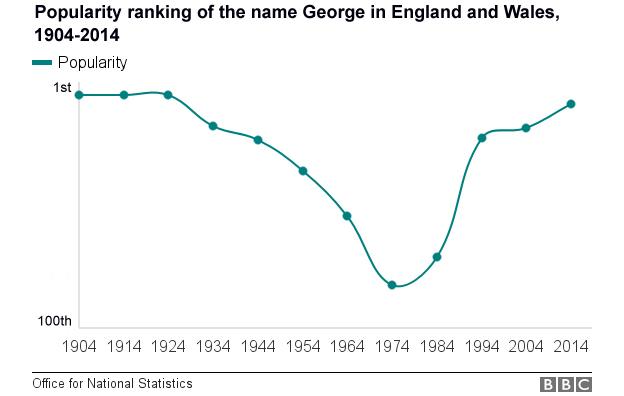

By George, the resurgence of the name started back in the 1970s

The traditional names affluent parents give to their children are far more likely to catch on than the zany names invented by some celebrity parents. But some, like George, rise and fall in popularity for no apparent reason, says author Neil Burdess.

Last week a Ukrainian man made global headlines for changing his name to iPhone 7. It's doubtful this will catch on, but for the last two centuries we've seen names rise and fall in popularity.

But it hasn't always been like this. For centuries, name giving was determined by custom, with most babies being given one of only a few names that were handed down from one generation to the next.

Even in the late 18th Century, more than half of all boys in Britain were baptised William, John or Thomas, and more than half of all girls were baptised Elizabeth, Mary or Anne.

Harvard sociologist Stanley Lieberson believes the Industrial Revolution caused this change in name giving. It weakened the influence of the extended family, and therefore the position of honour traditionally held by older people.

As a result, given names associated with the elderly became less attractive to new parents. The Industrial Revolution also speeded up the spread of literacy, and through their reading people came across a much wider variety of names - Dickens alone created a thousand named characters.

This is not to say that the custom of naming babies after family members has died out, as illustrated by the Royal Family - Philip begat Charles Philip Arthur George, who begat William Arthur Philip Louis, who begat George Alexander Louis.

Donald Trump Jr has been beside his father on the US presidential campaign trail

The Royal Family is not alone. One quarter of parents still do this, particularly when naming boys. Perhaps not surprisingly, US presidential candidate Donald John Trump's first son is Donald John, and his first son is Donald John.

But increasingly parents are following the fashion to give unusual names. In 2015, more than 60,000 different names were registered in Britain, 50,000 of them to only one or two children.

At the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of babies given the most popular names has been steadily falling.

Twenty years ago, 60% of girls and 70% of boys were given names from the top 100 - today it's only 40% of girls and 50% of boys.

Dickens characters such as Rose Maylie in Oliver Twist introduced Britons to botanical first names

What motivates parents to give unusual names? In part, it's an extension of what happened in the 19th Century. Parents then had Dickens - for example, his characters named Daisy, Flora, Rose and Rosa probably helped foster the Victorian fashion for botanical names for girls.

Parents now have Google - the Office for National Statistics lists the 7,500 different names given to three or more British girls (from Aabidah to Zyva) and nearly 5,000 different names given to three or more boys (from Aaban to Zyon).

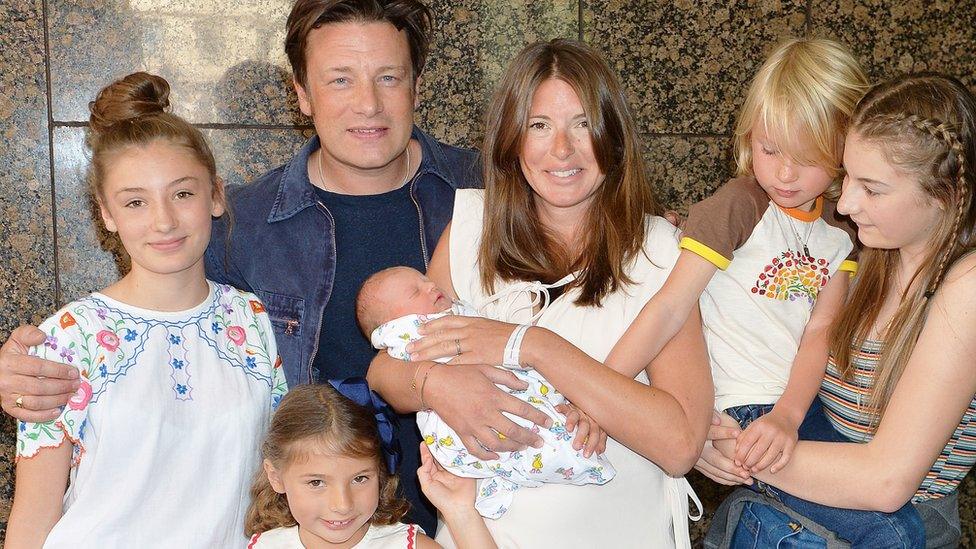

Jamie Oliver may have encouraged a trend to give children unusual names

Highly unusual names are, of course, common among the children of celebrities. Jamie Oliver's children come to mind - Poppy Honey, Daisy Boo, Petal Blossom Rainbow, Buddy Bear Maurice, and River Rocket.

It's likely high-profile celebrities such as Oliver have encouraged the trend to give unusual names.

Top 10 boys' baby names in England and Wales, 2015

Oliver, Jack, Harry, George, Jacob, Charlie, Noah, William, Thomas, Oscar

Top 10 girls' baby names in England and Wales, 2015

Amelia, Olivia, Emily, Isla, Ava, Ella, Jessica, Isabella, Mia, Poppy

But what about parents naming children after celebrities? People have been copying the names of their social superiors from the time of the Norman Conquest.

British historian Will Coster describes how 500 years ago "names could move down through the social structure, until they reached a point at which they would have ceased to be reused… New names were most likely to enter towards the top of society, working their way down, and occasionally being dropped."

Giving a child the name of a celebrity can be seen as a modern version of this historical process. It's most obvious when a celebrity's name is initially quite rare.

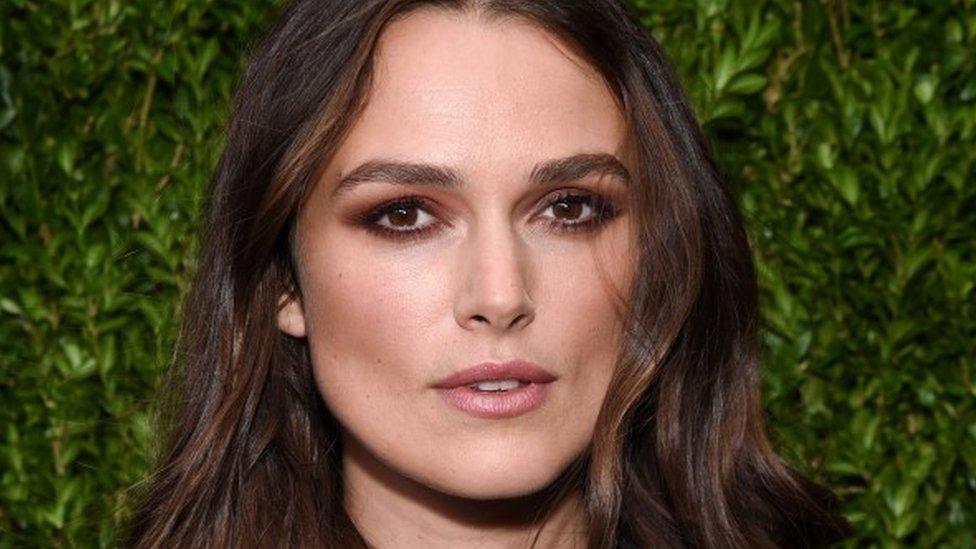

Keira Knightley's first name arose from a spelling mistake on her birth certificate

Keira Knightley would have been Kiera had it not been for a misspelling on her birth certificate. In 2001, Kiera was much more popular than Keira, but when Knightley's film career took off in 2002, Keira rocketed into the top 100 names in 2004. And by 2007, at the height of its popularity (and, perhaps, Knightley's) it was a top 50 name, with three times more babies named Keira than Kiera.

More recently, Knightley's film output has gone down - and so has the popularity of Keira, which left the top 100 in 2013 and is heading downwards.

Zayn is another unusual name that's become more popular recently. Zayn Malik was a member of the phenomenally successful band One Direction, which first performed in 2010. In 2009, Zayn was ranked 696th on the list of British boys' names, but climbed to 220th in 2015.

It seems reasonably certain that this change in popularity can be explained by Malik's rise to fame.

Zayn game: Malik's case suggests the perceived influence of celebrities on naming may be exaggerated

However, it's also instructive to look at the number of babies registered as Zayn - 43 in 2009 and 255 in 2015, an increase of only 200 or so, showing it's possible to exaggerate the role of celebrities in name giving.

In Britain, one of the most popular names recently is George. Following the birth of Prince George in mid-2013, one headline trumpeted: "George makes a comeback as parents copy Wills and Kate."

But as the chart shows, the comeback began in the 1970s when the name's long downward trajectory suddenly reversed, for no obvious reason, until once again it became a top five name.

It may be that more influential than celebrities are families who live nearby in more affluent neighbourhoods. Poorer parents may believe they can give their children a better chance of success in life by giving them names popular in richer areas.

A Californian study showed that once a name catches on among high-income, highly educated parents, it starts working its way down the socioeconomic ladder.

However, to quote researchers Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner, "as a high-end name is adopted en masse, high-end parents begin to abandon it. Eventually, it is considered so common that even lower-end parents may not want it, whereby it falls out of the rotation entirely."

In case you're thinking that this is just those crazy Californians, recall that Will Coster said exactly the same thing about 16th Century England. So, if you want to see some of the most popular British names of the next generation, a good place to start may be today's birth announcements in The Times.

Neil Burdess is the author of Hello, My Name Is … The Remarkable Story of Personal Names published by Sandstone Press on 3 November.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.