The match that pitted white players against black players

- Published

West Brom players Cyrille Regis (left) and Len Cantello (right) at kick-off

In 1979 West Bromwich Albion were looking for an idea for a benefit match for one of their longest serving players, Len Cantello. Somebody, we don't know who, came up with the idea of a match pitting black players against white players. Yes, really: blacks v whites, writes Adrian Chiles.

Warning: this story includes very strong language which some readers may find offensive.

It sounds somewhere between somewhat odd and downright appalling now, doesn't it? At the time, as I recall, it felt a rather progressive thing to do. After all we - I'm a lifelong West Brom fan - led the way in fielding black players. It seemed rather logical to push the envelope a little further and get a whole team together.

Behind closed doors, in the decidedly peculiar world of the training ground, this kind of thing had been going on for a while. "In five-a-sides we used to have the Jocks and the blacks versus the English," remembers Cyrille Regis, one of the stars of the black team. "I think the idea may have sprung naturally from that."

Watch a bit of the match

Cyrille Regis, Brendon Batson and Laurie Cunningham were our magnificent trio of black players, dubbed - again not in the best possible taste - The Three Degrees. They remember the game with pride and great fondness. Batson recalls no controversy. "Nobody ever rang us up and said, 'Do you realise the implication?' Nothing at all. It was fun. In that dressing room it was just great fun."

And all the black players I've spoken to about that day talk with feeling about that dressing room. Don't forget, all their lives they'd been outnumbered. Now, for one match only, they had a room of their own.

Back row, left to right: Ian Benjamin, Vernon Hodgson, Brendon Batson, Derek Richardson, Stewart Phillips, George Berry, Bob Hazell, Garth Crooks. Front row: Winston White, Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham, Remi Moses, Valmore Thomas

Having been an obsessed teenage fan in the 70s, I thought I knew all I needed to know about what my heroes went through in that era. How wrong I was. I've spoken to many of the players and I've been reminded of how simply awful it was, and bewilderingly complex too.

The horror of thousands of people chanting racial abuse, with bananas raining down on the pitch, is straightforward enough to appreciate. Although I found the sheer in-your-face loathing quite painful to hear the players recall.

Bob Hazell and George Berry, brought in from Wolverhampton Wanderers for the match, are clear: don't believe any player who says they could shut it out. "You heard everything, trust me. You heard everything," says Hazell with feeling. Berry nods, "Every racial chant, you definitely heard. But only if you took it on board and let it affect you did it become a negative."

And there lay the trick of it - to take the abuse, and see it only as motivation to spur you on. "It made you angry but we learned to channel the anger and motivation," says Regis, "and go, 'Right we're gonna show you how good we are.' And that was our way of dealing with our anger, to think how we could hurt them. You did it with your ability."

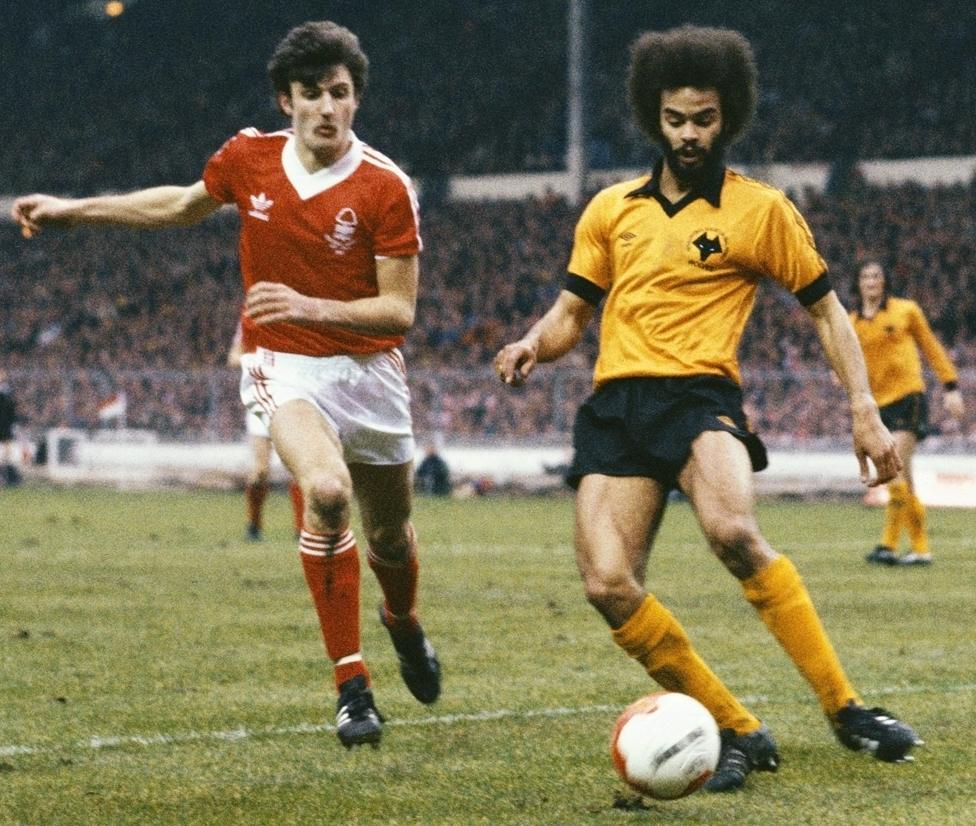

George Berry playing for Wolves in 1980

The superhuman mental strength required of these men only now really comes home to me. I share a troubling thought with Regis and Batson: "No disrespect - you're my boyhood heroes after all," I say, "but it strikes me that for every one of you, there were perhaps three others who were just as good as you, if not better, but didn't have the mental strength to survive the abuse."

"One hundred per cent," says Regis sombrely.

"No question," agrees Batson.

You'd have hoped and assumed that what our black heroes went through would have educated West Brom fans in the evils of racism. Well it did, and it didn't. It's not quite that simple. I once interviewed Simon Darby, then in charge of the British National Party in the West Midlands. I knew he was an Albion fan so I asked him who his all-time favourite player was.

"Cyrille Regis," he said immediately.

He saw me looking puzzled, and what he said next still chills me. "Just because I have him as a hero doesn't mean I want my grandchildren to be black." So you could love our black players, and sing their names, but still hold decidedly unsavoury views about them.

Cyrille Regis, 1978

When I tell George Berry this story, he recalls playing for Wolves at West Brom.

"I'm marking Cyrille on the near post at a corner. And all I can hear from this West Brom fan behind the goal is, 'You black bastard, fucking get back up the tree, you fucking golliwog.' And I'm marking Cyrille Regis! I just said to this bloke doing the shouting, 'Who are you talking to? Me or Cyrille?' Cyrille just shook his head."

In that West Brom crowd of course, there would have been the odd black fan. Talking to our supporters from the time has really brought home to me what black fans went through. The players, on the pitch at least, were only outnumbered 10 or 20 to one. For black fans it would have been tens of thousands to one. "I don't know how they did it," says Regis. "I really don't."

Find out more

Whites Vs Blacks: How Football Changed A Nation, presented by Adrian Chiles, will be broadcast on BBC Two on Sunday 27 November at 21:00 - catch up later online

Black and British is a season of programming celebrating the achievements of black people in the UK and explores what it means to be black and British today

Very few black fans braved it. One of them was Bernie Noel, a friend of mine. He runs gyms in prisons - a real tough guy. His arms are the girth of my legs. He describes the horror of the moment the fans around him used to start chanting racial abuse. "You'd feel part of a family enjoying all manner of songs, chants and boisterous activity together. They start making monkey chants and chanting 'You black bastard' to opposing players or fans. At those times you couldn't feel more alone."

Bernie wouldn't go back to those days but he does have an interesting take on how far we've come, which may not be as far as we like to think. "I sometimes wonder if I preferred it back in the 70s."

"Eh?"

"Because then," he explains carefully, "you knew who the racists were - they were shouting their heads off. Now I look around and think, well some of you are still thinking those things but I don't know who you are anymore."

Dion Dublin and Ian Wright at Crystal Palace

So many stories from the era, remarkably really, remain untold. Ian Wright and Dion Dublin are from the angrier generation of players that followed Regis, Cunningham and Batson. "We owe them so much," says Wright. "They had to turn the other cheek. They were Martin Luther King. I was more Malcolm X."

We meet at Crystal Palace, where Eric Cantona infamously lost his temper and karate-kicked someone in the crowd who was yelling abuse at him.

"I tell you," says Wright, as we walk past the spot where it happened, "any black player watching Cantona do that would have wondered how they stopped themselves doing the same thing.

"But imagine any of them back in the day, with all the abuse they got, jumping into the crowd. Do you think they would be playing football? They would have been locked up for that."

Good point. But on this occasion, Wright is wrong. When I relay what he said to George Berry, he looks half-sheepish, half-proud and says, "I did it." It turns out Berry did a Cantona a good 20 years before Eric got round to it.

George had made a mistake that led to Watford scoring in a cup tie against Wolves at Molineux. As he was coming off the pitch a Wolves fan started yelling at him. "One of our own fans was calling me a black bastard and a fucking disgrace to the club and saying 'Fuck off back to your country' and 'You're a coon' and the whole lot.

"As I started to walk up the tunnel at Molineux, I thought: 'I ain't taking that.' So I walked back down the tunnel and back up the track and I confronted him. Some of his mates started laughing. That was it - I lost it. I jumped in the crowd, gave him a right hook, and got arrested."

I think we can safely say George Berry would have made a rotten Martin Luther King, but who can blame him? The really amazing thing is that it was all hushed up. George wasn't charged, the fan's complaints, if he made any, apparently fell on deaf ears, and the TV footage, Berry was told later, was quietly lost.

My hunch is that the whole incident was considered too incendiary for words and it would be much better to pretend it had never happened. I applaud the cover up. Just like our blacks v whites match, it feels quite wrong now, but might well have been the best thing to do in the worst of times.

The match itself, by the way, finished 3-2 to the black team. Lots of black fans turned up to watch. There was no trouble whatsoever. A good day was had by all.

The players of 1979 reunited. Back row, left to right: Stewart Phillips, Ian Benjamin, Alistair Robertson, Tony Brown. Front row: Vernon Hodgson, Cyrille Regis, Brendon Batson

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.