Gullah Geechee: Descendants of slaves fight for their land

- Published

Descendants of West African slaves in South Carolina are fighting to prevent their land from being confiscated and auctioned. Can they save a traditional way of life that has survived for the one and half centuries since emancipation?

The first Lillian Milton knew about it was when she arrived at the local council offices to settle her tax bill.

She was told her home had been sold because she had not paid a $250 levy for a sewer service. She was shocked - at that point she had not even been connected to the sewer system.

"They had sold everything, the property, the house and all and when I offered to pay them with a cheque, they told me I couldn't. I had to get cash money - 880 some dollars that I had to pay them to get my place back.

"It's like they were saying if I didn't get on the system I wouldn't have no place to stay."

Milton suspects the heart attack she suffered in January was brought on by the stress of trying to get her home back.

Gullah Geechees fight efforts to confiscate ancestral land

In the end, she says, "my boss lady gave me the money," and she was able to pay the court fees to redeem her property.

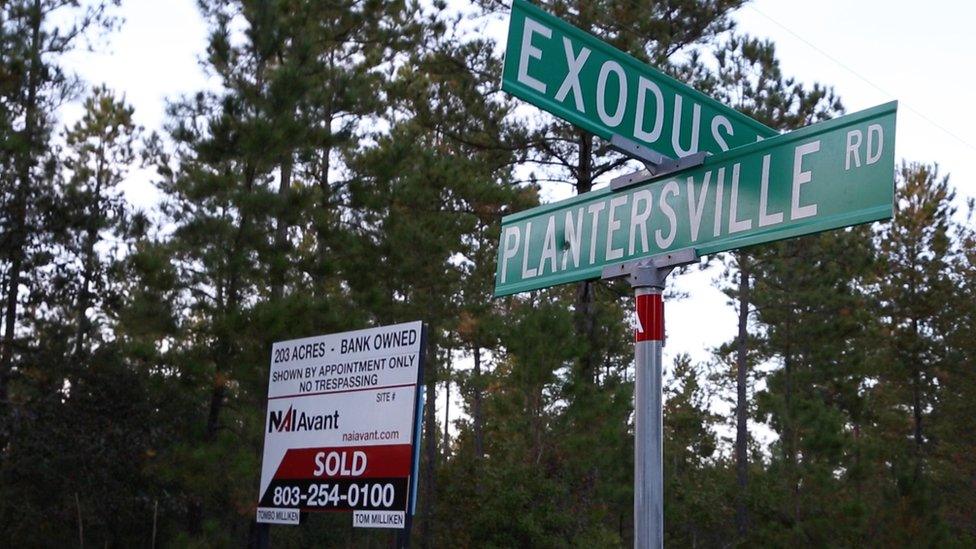

Many of her friends and neighbours in Jackson Village, one of three black communities in Plantersville, South Carolina, face losing their homes in a similar way if they don't pay the tax for a sewer they say they didn't want and don't need.

Last week 20 homes were put up for auction.

Most residents are the direct descendants of West African slaves, who bought land on the former rice plantation, or were deeded it by the government, after emancipation in 1865.

Property ownership had special meaning for these former slaves, known as Gullah Geechee, and the land has been proudly passed down through the generations, as a safe haven to raise families and farm.

But America's seemingly insatiable appetite for coastal living and the money that can be made from buying up cheap former plantation land is a potential threat.

"The only people we see are the developers," says the Rev Ben Grate, gazing at the empty road that snakes through Jackson Village.

"We call them 'strangers' and we are afraid of them. Because they come to take your land.

"They are millionaires, in big cars, driving slow, staking out property, dreaming on what it would be like to have a motel on the river right here."

With its neat brick-built bungalows, set back from the road in their own plots of land, and protected from the roar of Highway 701 by a dense forest, Jackson Village feels secure and cushioned against change.

But few residents here have deeds to their homes. The freed slaves who originally bought the land were mistrustful of the legal system, or excluded from it, and did not leave written wills.

The land is held in common. The families are entitled to live on it under "heir's property rights" - but so are all of the descendants of the original owners. Ben Grate estimates that more than a million people, spread out across America, have a share of land in Plantersville, whether they know it or not.

Planterville residents took their fight to the state Capitol

If one of them decides to sell their share of their parents' or grandparents' home, it can lead to the entire property being sold at auction.

So although they are living on prime real estate, much sought after for holiday homes, golf courses or country clubs, they cannot simply sell up for a fat profit.

The residents can also have their home seized and sold off if they don't pay their taxes.

Lillian Milton's property, which was valued at $46,700 by the Georgetown county assessor, was sold at a delinquent tax sale to a real estate developer for $1,236, according to documents seen by the Georgetown Times, external. Residents who have their homes taken in this way have a year to redeem them, as Milton did.

But like others I spoke to she does not think it is fair that they have to pay for a sewer system they were forced to connect to even if their septic tanks were working well.

Some are retired people on fixed incomes who say they simply can't afford to pay $250 a year for the next 20 years.

There is also indignation that the tax was not part of the deal when the system was first proposed 10 years ago. At that point, they were told they would only have to pay a one-off $590 connection fee.

The Gullah Geechee

The origin of the terms "Gullah" and "Geechee" is disputed by scholars - but it is generally accepted that Gullah people are located in coastal South Carolina and Geechee people live along the Georgia coast and into Florida

They can trace their roots back to West Africans slaves, mostly from Senegal, Gambia and Angola, who were forced to live and work on the rice plantations

Their distinctive, fast-talking creole dialect, external, which can still sometimes be heard, is a mix of English and African languages

Because they lived a largely self-sufficient life in small, isolated farming or fishing communities, often on sea islands, the Gullah were able to retain a strong link with their African cultural heritage

But their ancestral lands are disappearing fast under pressure from leisure and residential development

At the time, the local authorities argued that the Plantersville residents' septic tanks were becoming a serious health hazard and contaminating drinking water.

But some of the Gullah Geechee suspected an ulterior motive. Historically, the installation of a public sewer has often been the first step towards opening up an area for suburban development.

Some of the white landowners in Plantersville, who live in the old plantation owners' homes, the entrances of which can be seen as you drive through the forest to Jackson Village, also opposed the scheme, as they suspected it was being pushed by land speculators.

In 2008, Tee Miller, the then director of rural development in South Carolina for the US Department of Agriculture, came down on their side.

In a letter to the head of the Georgetown County and Sewer District, he expressed concern that the black residents did not realise that they would now have to pay a monthly tax to cover the loan repayments.

"Based on conversations that our office has had with residents, the media, and even some leaders in the community, this was not well conveyed.

"Nor was the fact that it would be mandatory for all residents to tap into the system and pay the service fees and additional taxes, even if their current septic tank was operating properly.

"This could have tremendous financial impacts on these residents. Therefore, it would clearly be in the residents' best interest to find an alternative without service fees and assessments."

Lillian Milton and daughter Linda Milton Eaddy are worried about their future

But the Georgetown County Water and Sewer District decided to press ahead with the project anyway.

The Rev Ben Grate says the Gullah residents are the victims of racial discrimination, because Plantersville's white residents did not have to hook up to the system.

He doesn't accept that the black residents' septic tanks were in worse condition, as the authorities argue, and after seeing his home and 19 others put up for auction last week, he sees this as a fight for the future of his people.

"We fear losing our home, our land and our tradition and our way of life," he says.

"That is all at stake here because where do we go from here? We would be back into slavery. We feel that the same thing happened to the slaves when they were coming over. They stripped them of their land and their homes and their way of life."

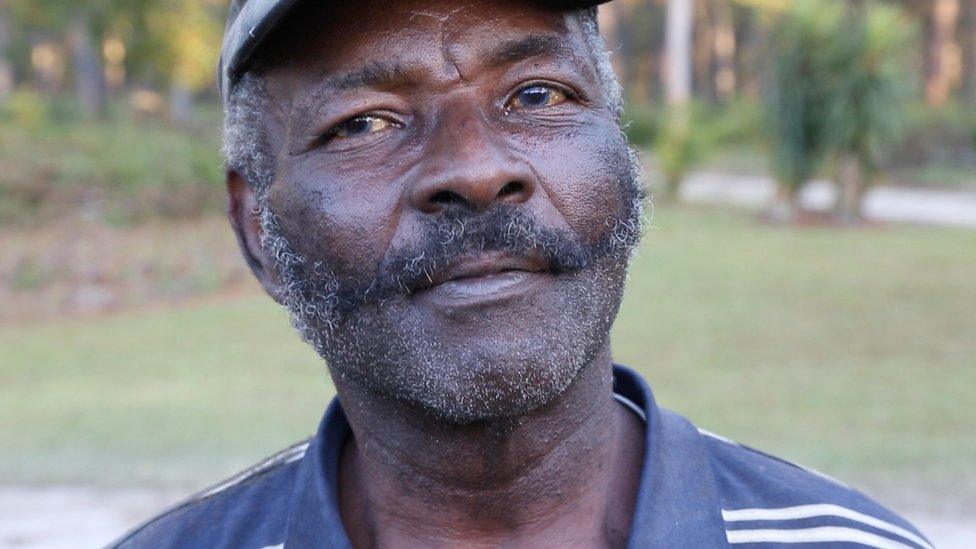

The Rev Ben Grate is leading the fight against the tax

Ray Gagnon, who recently took over as CEO of the Georgetown Sewer and Water District, disputes this, insisting it has nothing to do with race and everything to do with public sanitation.

He also insists that the Plantersville sewer was "never a development project" - and that the community voted "overwhelmingly" in favour of it, even when the tax bill began to escalate, and that they were kept fully informed of the risks at numerous public meetings.

It also had the backing of church leaders and county councillors, as well as the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which said residents badly needed access to good sanitation.

In July, a number of Plantersville residents took part in a protest march on the state capitol building in Columbia. Earlier, about 200 had signed a petition against the sewer.

But some of those who had initially held out against the tax have now scraped together the cash to pay it.

Ben Grate, however, is in no mood to cave in and is now attempting to draw the Gullah Geechee's plight to the attention of state governor Nikki Hayley.

The Milton family is standing with him.

"This is ours," says 48-year-old Linda Milton Eaddy, the daughter of Lillian Milton, as she watches the sun set on her family's homestead.

"We don't owe anybody anything on it. It belongs to us and we will not let them have it."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.