Why you need sackfuls of banknotes to shop in Venezuela

- Published

The pile of banknotes Gideon Long was given in exchange for $100

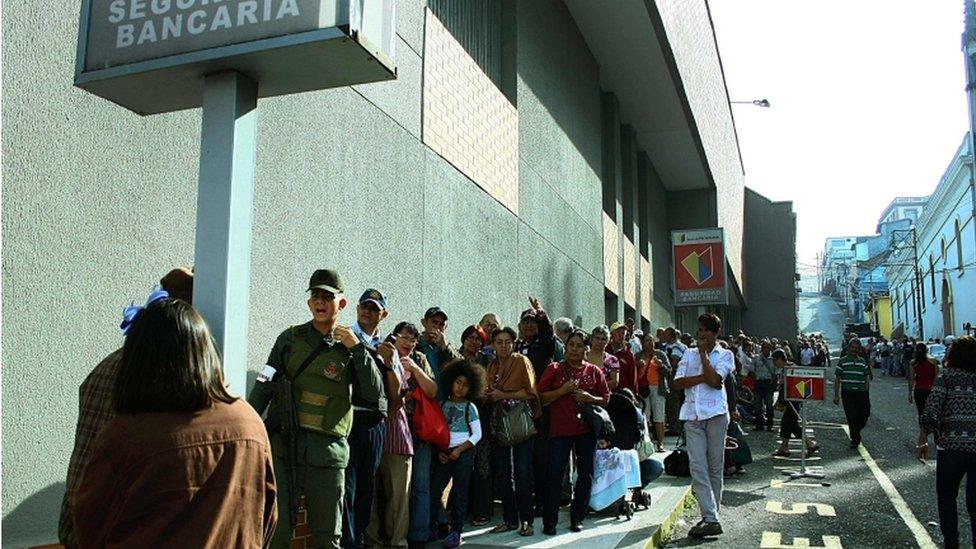

Last week Venezuela announced it would withdraw its highest-denomination banknote from circulation. Long queues formed outside banks as people scrambled to change theirs before they became redundant. The withdrawal of the 100-bolivar note has now been delayed until the start of January, but ordinary people must still grapple with spiralling prices and increasingly worthless notes, as Gideon Long reports.

"Have you changed money yet?", my friends asked me on my first evening in Caracas. I hadn't.

"Well, don't," they said. "Not at the official rate. Give us your dollars and we'll change them for you."

So I handed over a single US $100 (£80) note. The next day, I received two huge stacks of bank notes in return - and I mean huge. A thousand notes in each stack, 200,000 bolivars in total. I felt like I'd won the lottery.

Except, of course, this is no lottery and there are very few winners.

The losers are ordinary Venezuelans, whose salaries are losing value by the minute, and who have to queue for hours to buy basic foodstuffs that they can scarcely afford.

All this in an oil-rich country whose citizens were once famous for their international shopping sprees. It doesn't add up. To understand the mathematics of the situation, you'll have to bear with me - it gets complicated.

There are in fact three exchange rates in Venezuela.

If you're importing essential goods like staple foods and medicine, and you happen to know the right people in government, you can buy a US dollar for the state-controlled price of just 10 bolivars - a bargain!

Everyone else is supposed to change at the second government-controlled rate, currently 670 bolivars. But there's also a real-world, black-market rate, which has gone through the roof in recent weeks.

In October, there were 1,500 bolivars to the dollar. By late November there were well over 4,000.

The Venezuelan currency has strengthened since then but, even so, it's lost half its value on the black market in just a couple of months. My two towering stacks of bank notes were worth $100 when I entered the country. When I left two weeks later they were worth $50.

The 100-bolivar note, the biggest in circulation, is worth just two US cents. So when heading out for a coffee or a bite to eat, you had to take a sack of cash with you.

The central bank is now issuing bigger denomination-notes and new coins to make life easier, but that's causing its own problems.

With bank notes so worthless, cash machines can't cope - they can only dispense a few dollars' worth of money at a time. I never saw an ATM in Venezuela without a line of people in front of it - unless, of course, it was out of order.

"I come here every day," said Ramiro, a young man in a white T-shirt and red baseball cap, as he waited to withdraw a wad of virtually worthless notes from an ATM. "We're all wasting hours of our lives looking for cash."

Even if you do have cash, you can't always buy what you want.

Some staple foods - rice, flour, cooking oil - are sold at government-controlled prices. That makes them relatively affordable, but supplies are extremely limited, and you can only buy them on certain days, determined by the number on your national ID card.

"Monday is my day," said my taxi driver Alexander, a big man with an uncanny resemblance to Venezuela's late president Hugo Chavez. "I go to the supermarket every Monday. But even then, there's often nothing to buy."

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

No one even knows what the true inflation rate is in Venezuela. The government doesn't publish the figures any more. Last year, it was 180%. This year, the IMF expects it to hit 500%, and for GDP to fall by 10%. It's difficult to see how any economy can survive that.

The government blames lower oil prices and a US-led conspiracy to undermine the economy. This week, President Nicolas Maduro blamed the mafia in neighbouring Colombia for fuelling Venezuelan inflation with big, cross-border money deals.

But the truth is that Venezuela is suffering from its own chronic mismanagement. Zimbabwe, Argentina, the Weimar Republic - history shows us that when countries start printing money to prop up their economies, it seldom ends well.

The festive lights are now on in Caracas. The reindeers, the snowmen, the sleds - all look very incongruous amid the city's luxuriant, tropical vegetation. But this will be a difficult Christmas for thousands of impoverished Venezuelan families, some of whom are now facing genuine hunger in what used to be one of the wealthiest countries in South America.

As I sat in Caracas airport waiting to leave, I opened a local newspaper and found a cartoon. It showed a puzzled Santa, reading through a long Christmas wish-list. "But this is all food!" Santa is saying to an elf. The elf - grim-faced - looks back at Santa. "It's the Venezuelan list," he says.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.