Losing the most precious thing I own, 7,000km from home

- Published

While travelling through Kyrgyzstan, Eloise Dicker lost her late mother's treasured gold bracelet. Then a Facebook message changed everything.

It was on the second day of our five-day trek that I realised it was missing.

We had packed up the tents and loaded the horses. I reached up to the horse's mane to pull myself up and saw that my wrist was bare.

"My mum's bracelet! It's gone," I thought, and immediately burst into tears.

Made from melted-down rings she inherited from her own mother, the bracelet had always been worn by my mum for almost as long as I could remember.

Eloise Dicker's wrist with and without the bracelet

Her wrist was very slender even towards the end of her life, with steroids puffing her up like a blowfish. There came a point, however, when she couldn't wear it any more.

She had taken it off and placed it on her bedside table. While clearing up the cups and tissues, tablets and tinctures, I had picked the bracelet up and put it on.

She'd smiled, put her hand on my wrist and said how lovely it was to see me wearing it and that one day I would pass it on to my children.

She died a couple of months later, and I had never taken the bracelet off.

Rosemary Dicker, wearing the bracelet six months before her death on Mother's Day 2015

Now I felt pain in my throat and a sinking feeling in my stomach. It could be anywhere in this vast landscape - the Tian Shan mountains of Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia.

There was a silence as we all realised there was no point in even trying to find it. We were two days up into the mountains and surrounded by grass.

I had one last look around our camp. It was no use. I couldn't re-trace my steps, we were in the middle of nowhere. I climbed back on the horse.

I walked behind the others, crying and thinking. All the memories of her passing away came back to me, bit by bit.

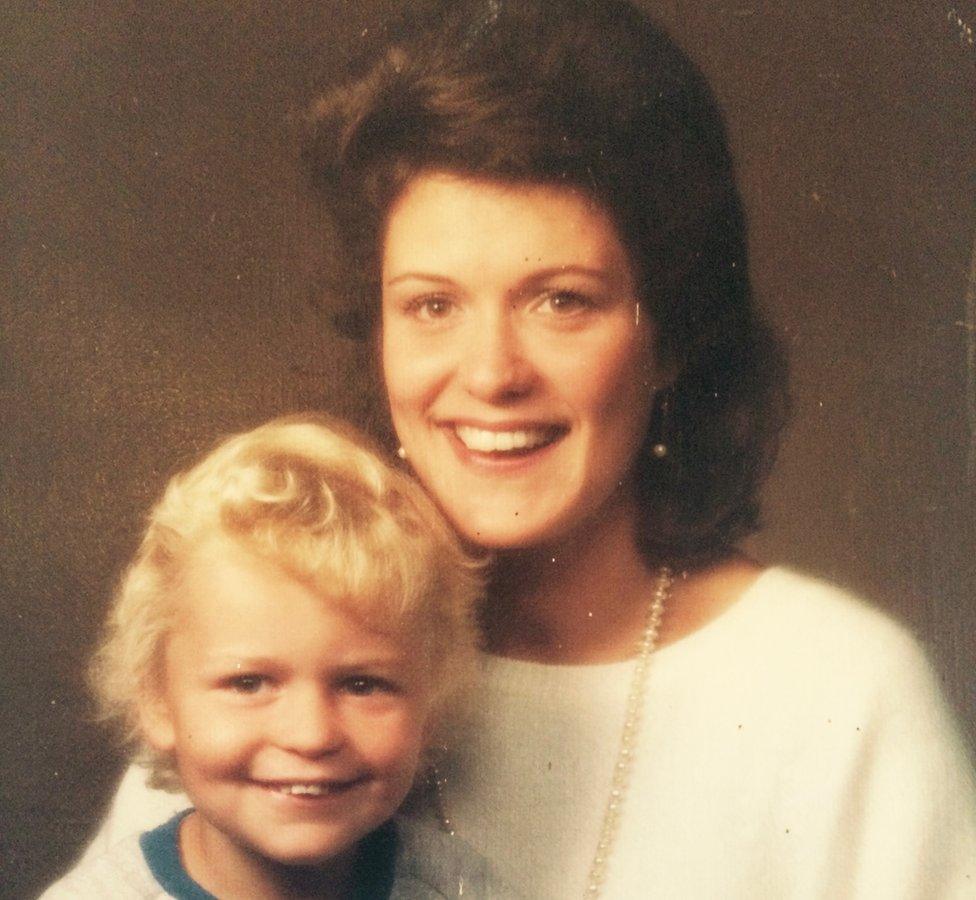

Rosemary holding Eloise's brother Barnaby in the early 1980s

My naked wrist still made me feel incomplete. I wanted to go back in time to the moment I decided to bring it with me. Why hadn't I left it at home?

But maybe it was meant to be here, I thought to myself. Mum was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the UK, and this was half way.

An endless lush landscape with wild horses, snowy peaks, birds of prey and the sound of the river. Maybe it should be lost here.

That night I looked in the tents with a bit of hope left that it might be in some corner. Nothing.

I crawled into my sleeping bag feeling deeply sad, and accepted it was gone for good.

Later, in the city of Karakol, recovering from our trek, I visited the Russian Orthodox church.

I was just about to leave, having lit a candle in remembrance of my mother, when the Russian nun took my arm and walked me to a painting of the Virgin Mary.

She kissed the glass frame of the picture and gestured that I do the same. I'm not a believer, and was not brought up religious in any way, but I followed her invitation.

When I kissed the glass I looked up at the picture. I started crying. The picture was adorned with gold necklaces and rings.

It was feeling just how jewellery was so significant to humans that made me cry. As a student of anthropology, I have always been interested in the meaning we humans ascribe to objects.

Jewellery by its very nature says: Look at me, see what I can afford, observe what I was given, admire how significant I am.

When inherited from a beloved, it also brings people into relationship, solidifying a kinship or affection, creating a sense of connectedness and of presence.

That bracelet was a physical part of my mother who is no longer physically in the world. It became part of me, and now was gone.

I had already made peace with the loss of the bracelet when, some weeks after I had returned to Europe, I received a Facebook message from Elaman Asanbaev, one of the guides from the Community-Based Tourism (CBT) office in Karakol.

There was a picture attached. "This is it or not, I don't know," he asked.

It was it. It was the bracelet.

It was suddenly back in existence, but what should I do? Should I get Elaman to send it? Should I leave it there? Ask him to throw it in the river?

When I looked into secure courier services, they advised against sending precious stones or metals. I was also reluctant to trust the postal system, it being so far away.

It did occur to me that I could find someone who would be travelling there, but when I saw that flights were cheap in November I decided I would go and get it myself.

London-Moscow-Bishkek. Then a six-hour drive from the capital Bishkek to Karakol with Azamat Asanov, the CBT manager. It was 05:00 and -11C in the capital, the roads icy with thick snow.

As we drove, I watched the country waking up. Children in their winter clothes walking to school, horses with snow on their backs, men in the traditional pointed Kyrgyz hats known as kalpaks.

The next morning we picked up Elaman. "This is for you," he said as he jumped in the car.

There it was. This slim piece of gold that I have known all my life.

This part of mum, here in this car 7,000km (4,350 miles) from home in the freezing mountains of Kyrgyzstan.

Elaman described to Azamat where he found it. I didn't understand anything except a word that sounded like "toilet".

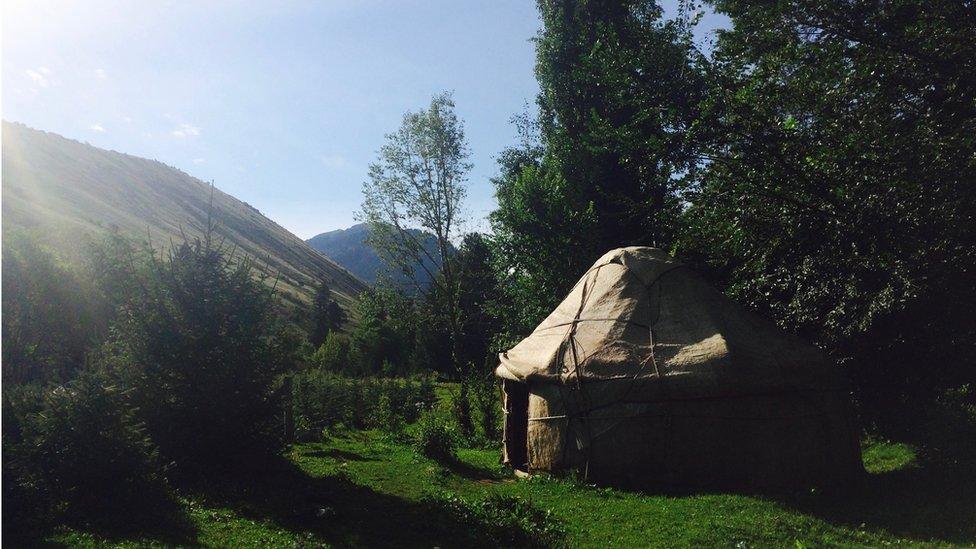

Azamat translated - it was in our first campsite, a yurt camp, lying on a path towards the toilets (or, more accurately, a shed with a hole in the ground).

We laughed. Not the most romantic of places.

I felt its weight and its shape. Mum held this. Putting it back on I felt complete again, and I couldn't stop looking at it.

I gave Elaman a designer flask and wrapped some money around it as a reward for handing in the bracelet.

There was another day in the snow on horseback before I turned round and made the long 21-hour journey back home.

We took the horses up the Bos Uchuk valley, which means "colourful point". This was where we had camped on our last day of the summer trek. I could recognise the shape of the mountains and the river.

On my way back to the town I sprinkled some of mum's ashes in the river - something to exchange for the bracelet in the ground, something to put her between home and where she was born, Hong Kong.

At this point I felt that these rituals were almost too much.

Yet back home, looking at photographs of mum, I notice the bracelet in every picture. I think how strange it is to know that it had a story waiting of being lost and found far away in a wonderful place.

Is this still the most precious thing that I own? Yes. Would I take it again on an adventure? Probably.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.