The housemates who found a lost plane wreck

- Published

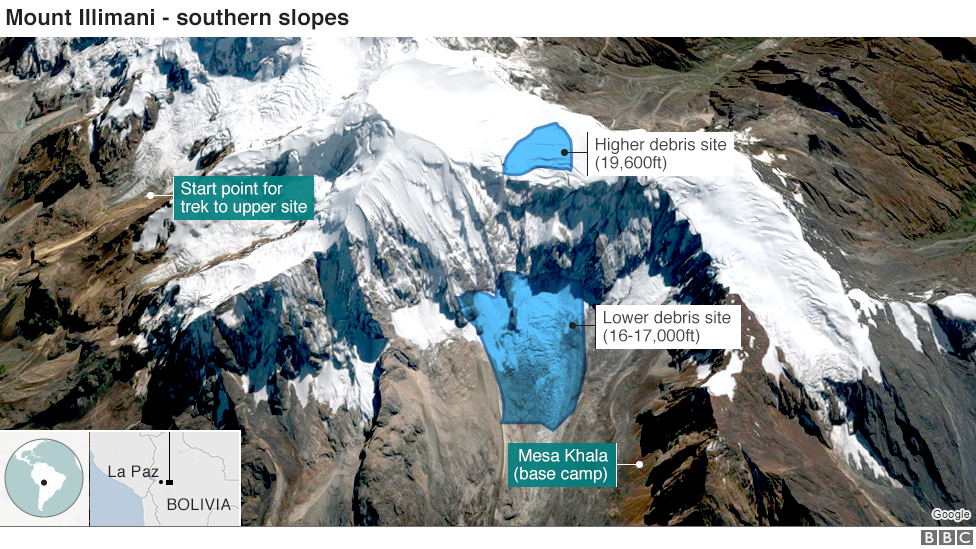

On 1 January 1985 a passenger jet crashed into a mountain in Bolivia killing all 29 people on board. No bodies were ever found. Nor were the black boxes that would have revealed the cause of the accident. But last year two young Americans decided to have a look themselves - and ended up achieving far more than official investigators.

"What are the chances that a couple of knuckleheads, with no mountaineering experience could actually go up to the top of this 20,000ft mountain and find anything?" asks Isaac Stoner.

"Still I thought it would be a neat vacation."

It was his flatmate, Dan Futrell, who came up with the idea one Saturday afternoon in 2015, as he idly browsed the internet looking for developments in the search for the missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370.

He found himself on a Wikipedia page listing 19 unrecovered flight recorders, and one immediately caught his attention - Eastern Airlines Flight 980, which had crashed in Bolivia in 1985, as it was coming in to land in the capital, La Paz.

Mount Illimani as seen from La Paz, Bolivia

Unlike most of the missing black boxes, this one wasn't at the bottom of the sea, it was on land. It hadn't been found, Wikipedia said, due to "extreme high altitude and inaccessibility of the accident location". But to Futrell it just seemed like "a typical Andean peak".

"We were on the couch drinking beer," Stoner recalls, "and Dan said, 'Look, this black box is just sitting on the top of a mountain in Bolivia. Let's go get it.'"

Futrell, 32, a former soldier who served two tours in Iraq, says he misses physical challenges now that he works at an internet company in Boston. So he seeks them out, and gets 31-year-old Stoner, who works at a biotech company, to accompany him.

They started finding out more about Eastern Airlines Flight 980. It had set off from Asuncion on New Year's Day 1985, heading to Miami via La Paz, carrying 19 passengers and 10 crew. The Boeing 727 had just been cleared to land at El Alto airport at 19:47, when it veered off course and crashed into Mount Illimani, the 21,000ft (6,400m) peak that towers over La Paz. Everyone on board was killed.

The crash site was located a day later by the Bolivian air force, however a search team was forced to turn back by heavy snowfall. In all, at least five expeditions made it up the mountain over the next 30 years, but none recovered bodies or flight recorders.

As contraband was often smuggled on flights from South America to Miami, conspiracy theories swirled around. Five members of one of Paraguay's richest families were on the flight, external and the US ambassador to Paraguay would have been on it too, if he had not changed his plans at the last minute. One unsubstantiated theory even alleges that a climber who reached the wreckage two days after the crash removed the black boxes to prevent a successful investigation.

Stoner started contacting climbers in Bolivia to see if two "ordinary guys" with no mountaineering experience could make the trip. One, Robert Rauch, said that they could.

"He told us 'I can put you right on the wreckage.' It turns out the glacier where the plane had crashed had retreated and there hadn't been much snowfall, so we might be able to see debris not seen for decades," Stoner says.

Rauch also revealed that some of the wreckage had fallen over a cliff, landing 3,000ft (915m) below the rest of the plane. This lower site was more accessible and a good place to start the search.

It was still high though. They would be operating at altitudes between 13,000ft and 20,000ft (4,000m-6,100m), where oxygen levels are 50% lower than at sea level.

Rauch warned them they would need at least three weeks in La Paz to acclimatise, but this was more time than they had available.

"We told him we had a total of two weeks' vacation," says Futrell, 32. "So he recommended we sleep in an altitude tent beforehand. We rented one and set it up in the basement. It pumps in nitrogen and simulates a low oxygen environment. It was awful and we would wake up with headaches."

Futrell and Stoner enlisted the help of experienced mountaineer Robert Rauch

Rauch also told the pair to build up their upper arm strength to prepare them for ice climbing.

"[We did] a lot of pull-ups with backpacks on," says Futrell.

"Isaac mostly attempted and I did all the pull-ups for both of us. I envisioned him hanging off the end of a cliff and me being the only person that could save his life."

"I envisioned cutting the rope and sending Dan down to the bottom of the abyss," jokes Stoner.

Other training included trekking up and down the steps of the Harvard Football Stadium in Boston. They also got a prescription for Diamox, which helps the body to absorb oxygen.

Isaac (left) and Dan bought ice axes and shovels in La Paz

One of the frequent avalanches that Dan and Isaac think are bringing wreckage down the mountain

On 17 May last year they flew to El Alto airport in Bolivia where they met up with their team - guide Robert Rauch, Bolivian cook Jose Lazo and journalist Peter Frick-Wright, who went on to write a detailed story for Outside magazine, external. After a few days of acclimatisation, they drove to a nearby peak to practise emergency drills.

The friends planned to split their time between the lower site Rauch had told them about and the impact site on the glacier, higher up the mountain, where the plane tail was still lodged in the snow.

"Robert decided that the best course of action would be to get us up on a mountain, to teach us how to ice climb, because we honestly didn't know what we were doing when it came to crampons and ice axes and being tied into a rope," says Stoner.

The housemates also struggled with the changes in temperature that veered from -6C (21F) in the shade to 9C (48F) in the sun.

"We knew we were going to suffer," says Futrell, "and in fact that was part of the draw of this trip. Worthwhile things are often challenging and that's what we were looking for."

Find out more

Listen to Dan Futrell and Isaac Stoner speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Get the Outlook podcast for more extraordinary real-life stories

The team set off for their base camp at 15,400ft (4,700m) above sea-level in a battered four-wheel drive, though two miles short of their destination they came to a halt. The road had been blocked by a rock fall, and they had to get out and walk.

"We camped at this spooky old abandoned mine with a view of the big cliff face where the crash had happened," Stoner says.

"Every now and then there was a distant avalanche that sounded like a runaway train. Apart from that it was silent. We were up above cloud level and it was really wild and beautiful scenery."

The next day they hiked for 45 minutes and, as Rauch had promised, they found themselves in the midst of the plane wreckage.

Debris was scattered over one square mile of rocky ground. Pieces of mangled plastic and wiring mingled with cutlery, wheels and broken cockpit equipment.

Flatmates Dan Futrell and Isaac Stoner look for the black box from Eastern Airlines 980

The first thing they saw, however, was a life jacket - "a piece of equipment intended to save somebody's life" as Futrell puts it.

"So not only did we know we were in the right spot, but we were instantly reminded that there's tragedy here for 29 families."

They had planned a grid search pattern but in their excitement decided first to go off in different directions to take a look.

Debris from the Boeing 727-225 was strewn across one square mile

Mangled metal, plastic and wires were visible

A pair of children's trainers were among the wreckage

The friends were busy picking through the wreckage when they were called by Rauch on their walkie-talkies. They rushed over to see what he had found. Slowly they realised they were looking at a human femur lying among the rubble.

"We all took a moment. We tried saying a few words but couldn't come up with anything," says Stoner.

The discovery disproved one conspiracy theory put forward by former Eastern Airlines pilot George Jehn in his book Final Destination: Disaster. After no remains were found on the first five expeditions, he suggested a bomb had depressurised the cabin and sucked the passengers out of the plane. This would have flung the bodies far from the wreckage. However, Futrell, Stoner and their companions found six body parts in separate locations.

One of the rock stacks the team used to mark human remains found on the mountainside

Cutlery from on board the Eastern Airlines 980 flight

One of the windows from the plane and orange metal found at the site

They decided to bury each find and mark the spot with a geomarker and a stack of rocks, in case anyone wanted to retrieve them later on.

"We also found silverware from the meal service, a sink from one of the bathrooms, shoes and shirts and jackets with pilot stripes on them. We found the emergency slide and life jackets, plane windows, landing gear and part of the instrument panel from the cockpit," says Futrell.

"There were wires everywhere and thousands of reptile skins which were likely to have been contraband."

However, there was no sign of the black boxes, which despite their name are typically bright orange.

"We were finding orange bits of metal the whole time, but I was holding on to the hope they weren't pieces of the black box as they are supposed to withstand a plane crashing into a mountain," says Stoner.

But on the final day of searching at the lower site, Stoner unearthed a piece of metal with a label attached to some wires that read "CKPT VO RCRD" an abbreviation of Cockpit Voice Recorder.

Wires labelled "cockpit voice recorder" suggested the team were on the right track

They decided this probably meant that at least one of the recorders had broken apart.

Not far away, they found a spool of magnetic tape.

Would this hold a recording of the final moments of the aircraft? Futrell describes this as his "greatest hope".

After three or four days at the lower site, the team decided to move on to the higher debris site and drove to a higher base camp. They set off at 04:30 the next morning but soon ran into serious problems.

"We had wanted to get up there and back in one day but we found we didn't have the time to do it. We were going slower as we were inexperienced at mountaineering and new crevasses had opened up which meant we had a longer and more difficult route," says Futrell.

They eventually decided it was too risky and turned back.

Dan and Isaac spent time digging out debris. At times the high altitude make them feel nauseous

The team: (from left) Dan Futrell, Isaac Stoner, Peter Frick-Wright, Jose Lazo, Robert Rauch

Returning to La Paz they boxed up the orange pieces of metal, wires and tape they had found and flew home with them to Boston. They suspected this might be breaking the rules of air investigations but decided it was the right thing to do anyway.

"We knew there was a specialist government lab in the States that would give us the best shot at an answer as to why the plane went down. Plus it was a US airliner and there had been no Bolivians on board," says Stoner.

Back home in the US, though, they had a problem. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the US department in charge of investigating plane crashes, didn't want to touch their packages.

"They said 'Great job guys, but we can't do anything with it unless we get Bolivian sign-off,'" says Futrell.

The housemates then spent months sending emails and letters and telephoning Bolivian officials.

"So at this point the black box has been sitting in our apartment on the kitchen counter next to the dog food for seven months," Stoner said at the end of 2016. "And really it's become a key part of the decorative aesthetic in the apartment."

Finally, in December, they were contacted by Capt Edgar Chavez, operations inspector at the General Directorate of Civil Aviation of Bolivia, who gave the NTSB permission to analyse the material.

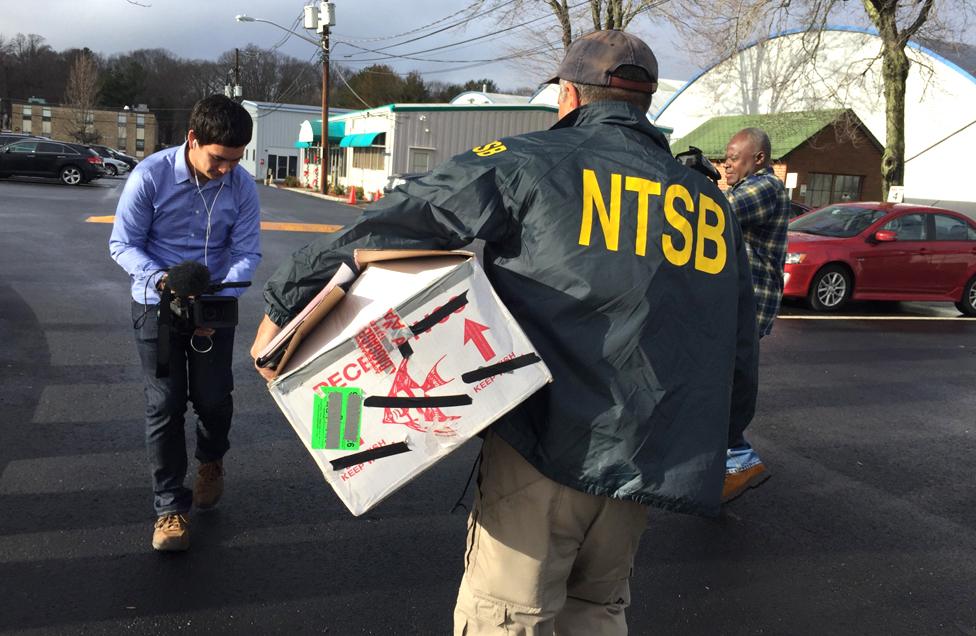

So on 4 January, Futrell and Stoner handed over the plane fragments to Bill English from the NTSB, who took them to a laboratory in Washington.

Bill English picks up the plane fragments that had been sitting on Dan and Isaac's fridge

The housemates had already concluded that poor weather, the tricky descent to El Alto airport and unreliable equipment had all probably played a part in the crash. However, data from the voice recorder might give conclusive answers to the families who had lost their loved ones.

"We had people reaching out from Paraguay, we had family members reaching out from the US, right down to an old girlfriend of the pilot calling me on the phone," says Stoner, "and most of them just really did want to say, 'Nice job guys, thank you.'"

One of the family members was Stacey Greer, the daughter of Mark Bird, the flight engineer on Eastern Airlines Flight 980. Greer was only two years old when her father was killed.

"I was surprised that someone would be interested in finding out what happened. It gave me hope that people still care," Greer says.

She had asked Futrell and Stoner to bring back some metal from the plane for her.

"It was a really touching meeting," says Futrell. "She got to put her hands on pieces of the plane, the last plane that her father flew and that took his life. She took this metal home and she turned one of the pieces of metal into a necklace just in memory of her dad and his loss."

"Usually there is a grave site or a memorial for a lost one, but my family never had that. Now we have something," Greer says.

The items studied by the National Transportation Safety Board in the US on behalf of the Bolivian authorities

On 7 February 2017, the NTSB released a statement, external.

Futrell and Stoner had not found the cockpit flight recorder, it said, but rather the rack that had fixed it on to the plane - and the promising spool of tape turned out to be "an 18-minute recording of the 'Trial by Treehouse' episode of the television series 'I Spy', dubbed in Spanish."

"Needless to say, we're disappointed," Futrell wrote on his blog, external.

However, it means both the recorders are still up on the mountain and could still be intact. Futrell and Stoner hope others will now follow in their footsteps.

Already one member of the US Forces has declared his intention to organise an expedition to recover human remains.

"This tragedy really deserves a formal, resourced, governmental investigation," says Futrell. "We've proved that 'inaccessible terrain' is an unacceptable reason for failing to close this investigation."

Additional reporting by Lucy Wallis

Photographs courtesy of Dan Futrell and Isaac Stoner

Listen to Dan Futrell and Isaac Stoner speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.