Mixed-race couple: 'The priest refused to marry us'

- Published

Trudy and Barclay Patoir met during World War Two at a time when mixed-race relationships were still taboo. More than 70 years later they reveal the obstacles they had to overcome to stay together.

When Trudy Menard and Barclay Patoir told friends and family they were going to get married, no-one thought it was a good idea - because Trudy was white and Barclay was black.

"When I told them at work they thought I was daft marrying a black man. They all said, 'It won't last you know,' because it was a mixed-race marriage," says Trudy.

"I think some people thought I was marrying beneath myself."

When the couple had first met, a year or so earlier, Trudy admits she too had been uneasy.

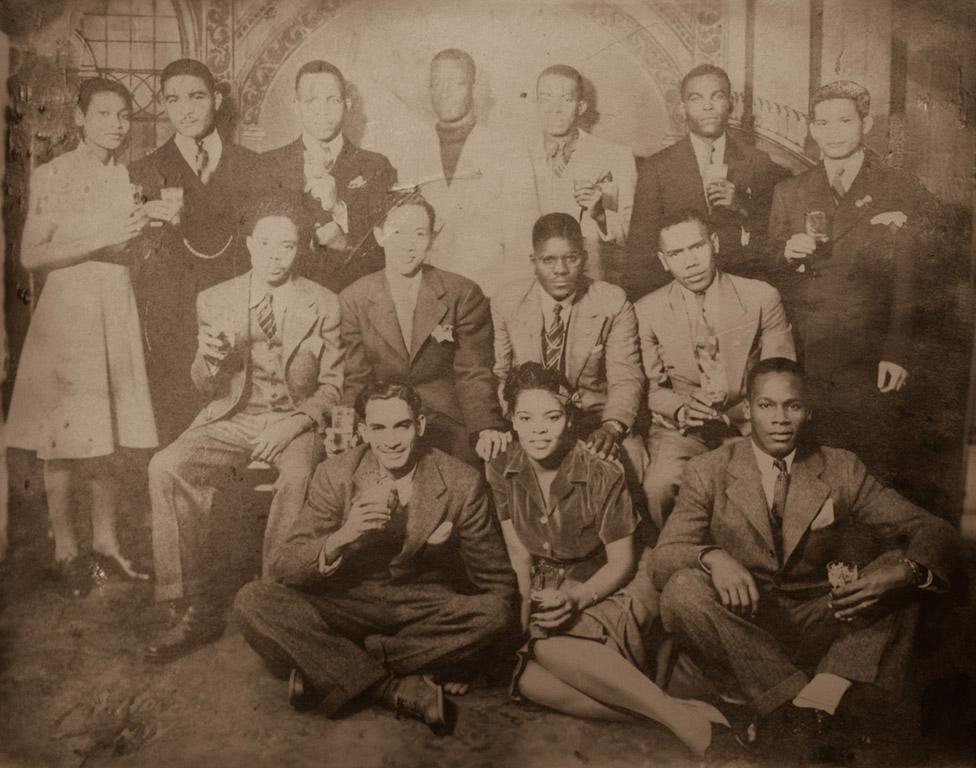

Barclay (bottom right) with fellow volunteers in the US en route to Britain

"I had been working at Bryant and May's match factory, but it got bombed in the Blitz," says Trudy, now 96.

"I needed a new job and was told they wanted girls at the Rootes aircraft factory in Speke. We were paired up with engineers and they told me to go with Barclay. I said, 'I'm not going with a coloured man. I've never seen one before.' But they told me if I didn't I'd be sacked so I just got on with it."

Barclay, 97, was an apprentice engineer who had travelled to the UK from British Guiana in South America, now known as Guyana.

"There was a shortage of engineer skills in Britain in World War Two so young men from the Caribbean volunteered to help the mother country," he says.

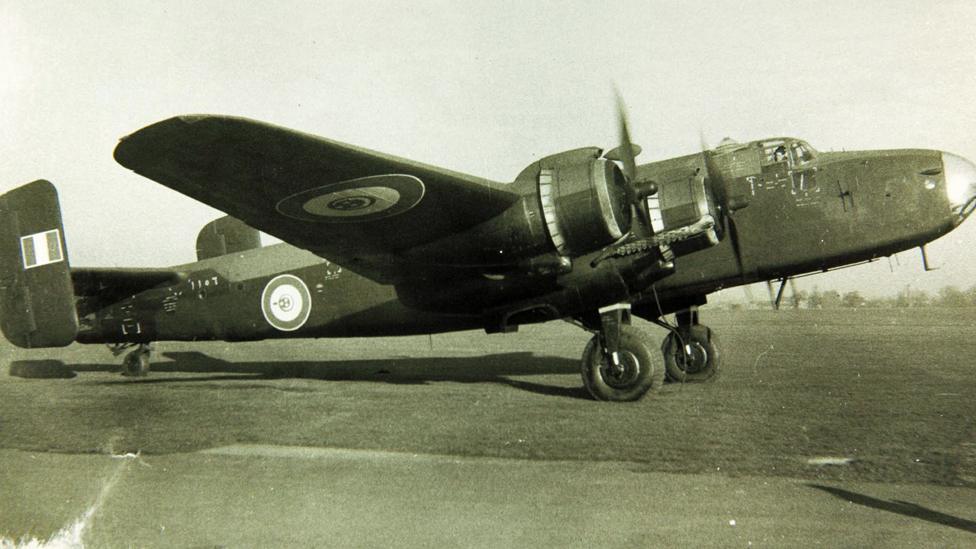

Between 1941 and 1943, 345 civilians from the Caribbean region travelled to Liverpool under a scheme to increase war production. Barclay was assigned to work on Halifax bombers at the factory in Speke and Trudy was chosen to work as his assistant.

Barclay (left) pictured with the Duke of Devonshire at Downing Street

"He stood on one side of the wings with a drill and I stood on the other side with the dolly. I was frightened to death of him - I'm not frightened of him now!" says Trudy, laughing.

"We didn't speak for a while and then he started to bring me a cup of tea, and then he started bringing me sandwiches."

Over time the pair became firm friends.

"We used to talk about Liverpool and history. And she was very inquisitive about Guiana," Barclay says.

"The others at work used to say, 'They're never going to come down now, they're talking too much,'" Trudy adds.

The couple worked together on the wings of Halifax bombers

They went out for the first time when production at the factory slowed down and staff were given a chance to take time off.

"I took him to Southport on the train. We got some dirty looks then. I could tell some people were talking about us on the train but we took no notice, did we dear?

"When we got there we had something to eat and on the way back we went to his place, the hostel, for a cup of tea. And all the lads were so happy to meet me," Trudy says.

Liverpool had the longest-established black community in the country, however racism was still very much apparent in the 1940s. A study of West Indian workers' experiences in Liverpool found that while many white women would talk to black colleagues at work, they would ignore them in public. They feared "the attitude their friends or their family would adopt if they found out that she had been out with a coloured man," writes the author of the study, Anthony Richmond.

It was a prejudice that Trudy and Barclay were all too aware of.

"I didn't tell my mother when I was going to see Barclay," Trudy says.

"She thought I was going in to town to meet the girls. She had noticed I was very happy but she didn't know why.

"When she did find out she threatened to throw me out the house."

Trudy and Barclay went to watch the Austrian tenor, Richard Tauber, perform

The couple would go to tea rooms and sit in the park together. One special date was to a concert by the Austrian tenor Richard Tauber, who was touring the country.

"We saw him at the Empire Theatre. He sang 'My heart and I.' That's our song," Trudy says.

"I knew then that I couldn't live without Barclay, but I didn't dare tell anybody for months."

Eventually, in 1944, after they had known each other for about a year, Trudy decided she was ready to take the plunge and told Barclay she would like to marry him.

"He said to me: 'It's going to be very hard, you know that don't you?' And I said: 'Yes, I know.'"

Trudy was keen to have a church wedding but the priest at the local Catholic church in Liverpool refused to perform the service.

"He said, 'There's so many coloured men coming over here and going back home leaving the women with children. So I'm not marrying you.' We were upset about that," says Trudy.

However, they were determined to marry and settled for a brief ceremony at the Liverpool Register Office.

"Only Barclay's friend and one of my sisters went. The four of us went for a meal afterwards," Trudy says.

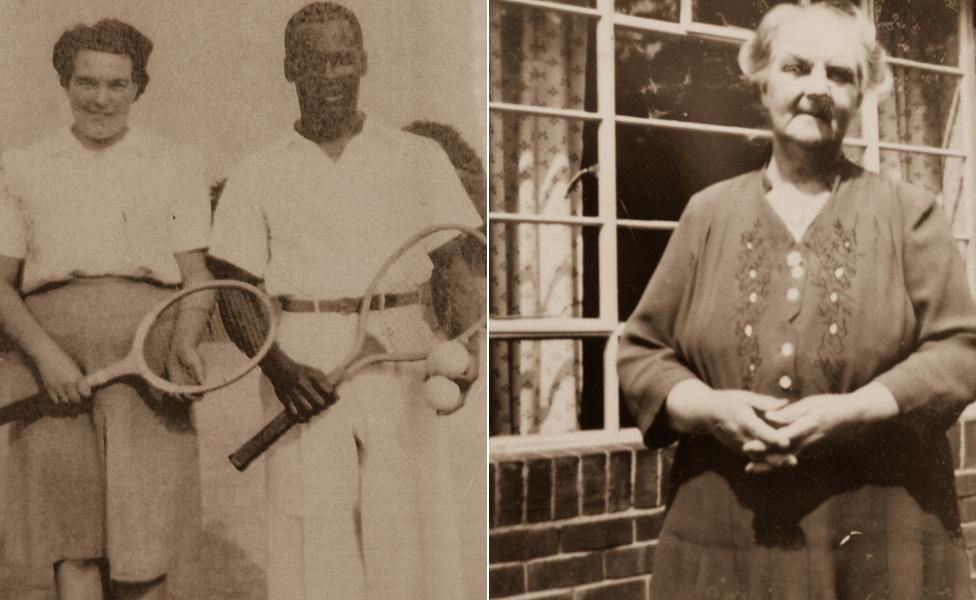

Trudy and Barclay playing tennis, and Trudy's mother Margaret

Shortly afterwards they decided to leave Liverpool.

"I had a friend who told me: 'Come to Manchester. It's more hospitable and there aren't as many racial problems,'" Barclay says.

"But it was difficult to find accommodation because nobody would have you if you were a mixed marriage."

They eventually got a room in a boarding house where Barclay's friend lived.

"The landlady had lodgers in but she took us in anyway and gave us her big front room," Trudy says.

"She was a prostitute herself but what a good woman she was."

Barclay continued to work in Liverpool, returning to Manchester at night. When the war ended he took the option offered to volunteers from British colonies to remain in the UK. However, it took him some time to adapt to his new home.

"You've got to have a good mentality to survive. I missed my family for about 10 years - I used to dream about them. And I found the freezing cold hard. I was used to a tropical climate," he says.

"He had more clothes on in bed than he took off!" Trudy adds. "He couldn't get warm in bed at all."

Barclay missed the family he left behind in Georgetown, British Guiana, pictured here in 1941

Barclay found it difficult to find a new job and ended up walking the streets of Manchester looking for work. He was eventually hired by the Manchester Ship Canal dry dock.

The couple settled in to their new life in Manchester. They joined the local sports club, where they played tennis.

"We won a set of cutlery in the doubles," Barclay says.

The local Catholic priest agreed to perform a second wedding ceremony for them in his church. Two daughters - Jean and Betty - followed, and the young family were desperate to get a home of their own.

"The priest mentioned that they were building houses in Wythenshawe," Barclay says.

"Nobody from Manchester wanted to live there, as there we no shops, just fields."

Trudy and Barclay on the secrets of a happy marriage

Trudy went to have a look at the new housing development.

"There was thick mud everywhere and I had a baby in my arms as I stood looking at the place. I couldn't get inside to look but I didn't care. I couldn't live in one room any more."

She went straight to the Town Hall and told them they would take one of the new houses.

"We were jumping for joy when we got the key," Trudy says.

Jean and Betty Patoir. Trudy made sure her daughter always looked neat and tidy

The Patoirs were one of the first families to move into the area.

"We were the only mixed-race couple there but we didn't have any trouble in the community," Trudy says.

"When this place filled up everyone loved our girls."

However, their daughter Jean did encounter bullying on her first day at primary school.

"The teacher sent her home and asked me to keep her home while she had a chance to talk to the school about how God loved all his children. Jean didn't have problems after that," Trudy says.

Trudy's mother Margaret also changed her attitude towards Barclay after her granddaughters were born.

"She would come every weekend to stay - she loved seeing the girls," Trudy says.

Trudy and Barclay celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary in September 2014. They received congratulations from the Pope (above)

Both Trudy and Barclay think attitudes to mixed-race relationships have improved dramatically over the decades.

"Before people would stop and watch you, or whisper and laugh as you passed and now they're not bothered," Barclay says.

"People don't walk on the other side of the street like they used to," Trudy adds.

Barclay has been very active in the community over the years. He has been president of the local social club, a school governor and sat on the local hospital board. He got involved in local politics after he stopped working at the dry dock in 1979.

The couple now have two children, three grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

"It's hard to keep track of them all," Trudy says.

They received congratulations from the Queen and the Pope on their 70th wedding anniversary in 2014.

"We discuss things if we don't agree. We never really had a big argument," Trudy says.

"We're so used to each other, we don't aggravate each other," Barclay agrees.

While Trudy says she "can't put her finger on" what she loves most about Barclay, her husband has a ready answer.

"Trudy is genuine, she's a partner," he says. "Every morning I wake up I thank the Lord for having such a good wife."

Trudy and Barclay have lived in the same house for 70 years

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.