Wheelchair man: Turning myself into a superhero

- Published

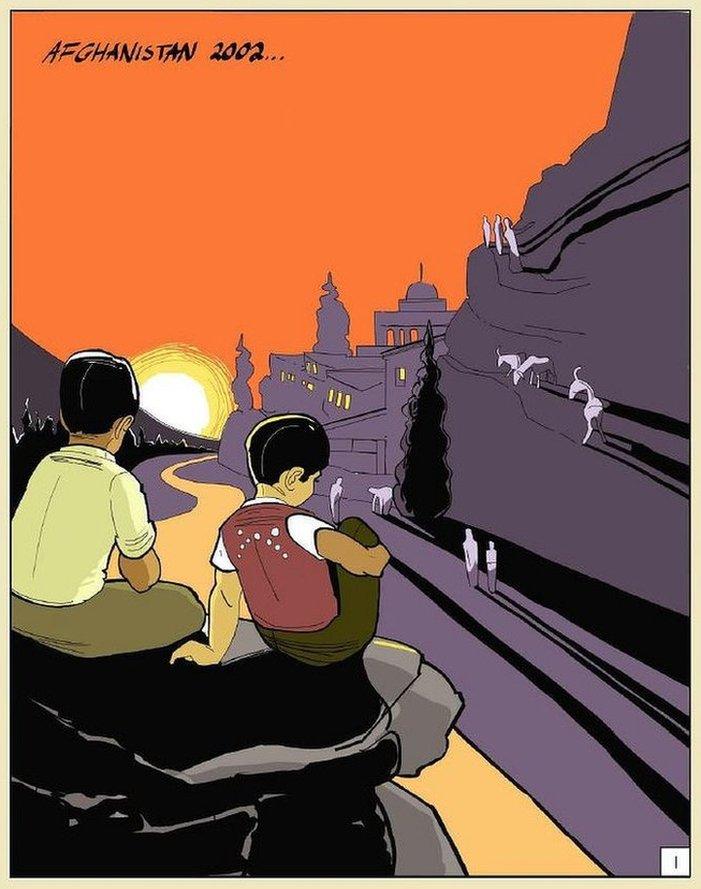

Mohammad Sayed was abandoned by his family in Afghanistan after his house was bombed and he was left paralysed. Now he has become a US citizen, and designed a comic book superhero - Wheelchair Man - based on his own life story.

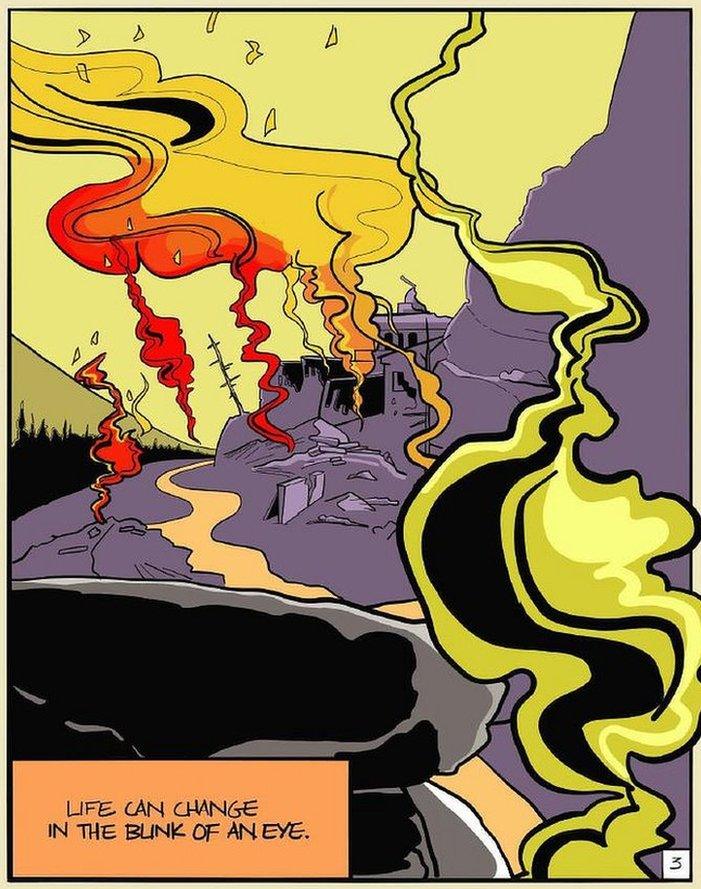

I used to play with my father's AK47, rocket launchers and used mortar shells. We didn't have toys and every household had them. They made me feel powerful and I used to brag that I was not scared of the bombs raining down on us. But eventually one of those bombs fell on me.

I lived in the Panjshir valley with my mom, my dad, my two brothers, my sister and my grandmother. My father was a commander with the Afghan National Army (ANA) in charge of 300 soldiers.

My mother died when I was between five and six years old, I don't know the exact year, but I think it was around 2002.

Eleven days later I was seriously injured. It was so traumatic that I don't really like to go into the details.

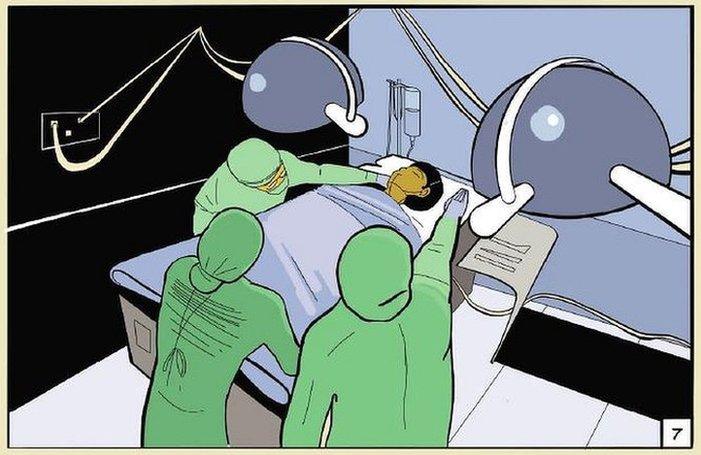

My father took me to a hospital that day and never came back for me, so I had to take care of myself.

For the first couple of weeks all I could do was cry. But people in Afghanistan are very resilient - you face challenges, but you have to get up and move on, and that's what I did.

The hospital was run by Italians and it had about 500 employees.

After six months my medical needs had all been seen to - I have a spinal cord injury and I can't walk now, I'm in a wheelchair - but since I didn't have anywhere else to go they gave me a bed in the corner of a ward where I lived with the other patients. That was my home.

I had to pay for my food and clothes, and take care of myself, so I started a little business repairing the cell phones of the employees - the cleaners, cooks and guards at the hospital.

Cell phones had just come to Afghanistan and a lot of people there are illiterate - because of the war they never went to school. They couldn't even read in Farsi and the phones were in English. So they would have simple problems with their phones, I would fix them and they would give me a $2 or $3 tip (£2.40), which was a lot of money.

Then I figured out a way to make cell phones hold their charge for a day or two longer, and started making money that way.

I would also teach the foreigners in the hospital Farsi. We'd bond over time and when they left Afghanistan they would often give me a good amount of money, perhaps $20 (£16), which was a lot of money in those days.

Dr William, the American doctor through whom I met my mom, left me $600 (£480), and there was another doctor who left me 600 euros (£507). I was a hustler and I was hitting the jackpot.

The head of the hospital had a safe where the money was kept. Whenever I needed it I would go to him and he would give me what I needed, but my businesses were doing well so I never used most of that money.

When I came to the US I actually brought $600 (£480) of savings with me.

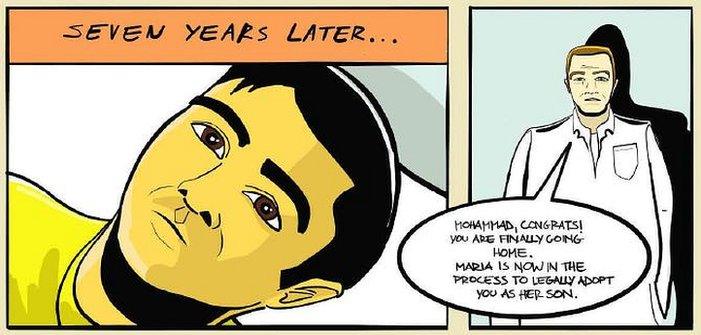

Well, I lived in the hospital for seven years, and I went to school and had my little businesses repairing cell phones, but unfortunately in 2007 the hospital abruptly shut down. It became like a ghost town and I was the only living soul in it. I had to figure out a way of taking care of myself again.

One day I was sitting in the hospital and one of the guards came to me and said there was a blue-eyed woman looking for me. I thought that was pretty strange, I'd never met a blue-eyed woman.

So I came down and there she was, Maria Pia Sanchez. She was a nurse, a friend of Dr William, and very nice. Whenever she came to Afghanistan for work she would come to visit me and eventually she said she would like to give me a home in the US.

In 2009, at the age of 12, I came to the US to receive medical treatment to straighten my spine.

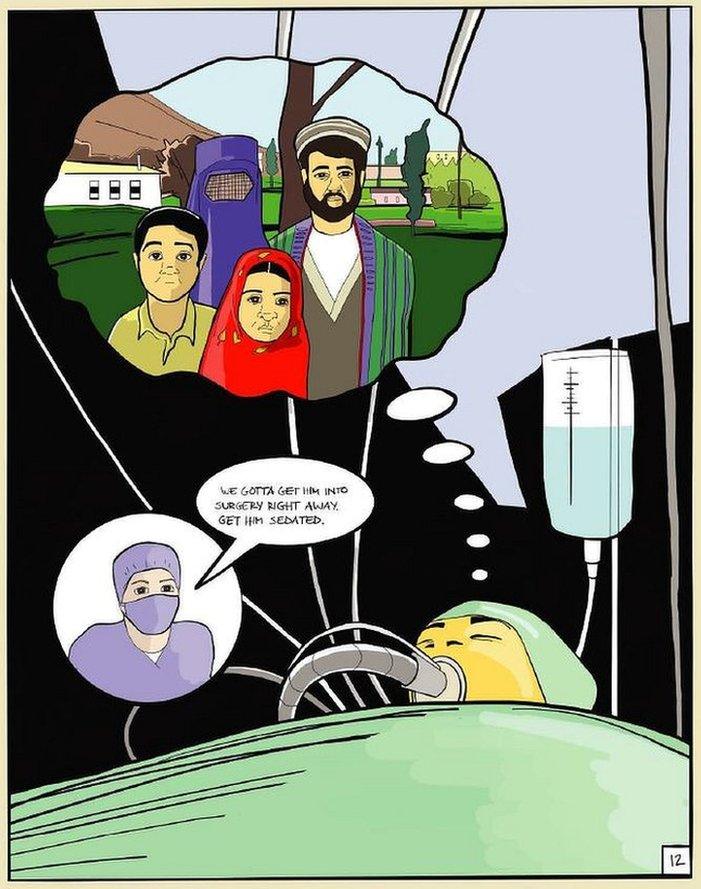

I had more than 12 operations, I lost so much blood, it wasn't good.

I tell people that I have died three times and come back to life - one was when I had my accident, one was when my father left me, and the third time was when I had this surgery.

But now I'm doing very well, my back is straight and thankfully I don't have pain any more.

The doctors said that if I had stayed in Afghanistan my life expectancy would have been 18. Now I'm 20, so I'm definitely making progress.

But it was scary coming to the US, it was like going to a new planet.

Going to school with girls was very challenging because in Afghanistan my teacher and classmates had all been male.

I now had a female teacher and my principal was female. Eight of my classmates were girls and they would come to school in shorts - that's kind of considered being naked in Afghanistan.

So it was hard to get used to, it was a culture shock.

And my teachers would get so mad when they talked to me because I would look down - that's very respectful in Afghanistan. They'd say, "Look me in the eye when I talk to you!" There were a lot of cultural misunderstandings.

It was emotionally hard for me too, because I was feeling that I wasn't as smart as I'd been in Afghanistan. I was the top of my class there, but now I was new and although I could speak and write English my grammar and spelling were bad. I would feel really depressed that I was not good compared to all my classmates. But eventually I did learn and did very well.

I'm very creative and always try to solve problems, so when I heard about this school called NuVu - a STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) school founded by MIT students - I really wanted to go there.

I went to meet the head of the school and I said, "This is exactly where I want to be, I want to come here!"

But then I learned that you had to actually pay. I told them, "I don't have money, I really want to come here, but I don't have money."

I think I was the first student that they gave a scholarship to. I went there in 2014 for about two years and learned a lot about engineering.

Find out more

Listen to Mohammad Sayed speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Get the Outlook podcast for more extraordinary real-life stories

I would look all over the internet to buy stuff for my wheelchair. A lot of companies make products for wheelchair users but they're not in wheelchairs themselves, so they over engineer them and then sell them for such a high price that most people can't afford them.

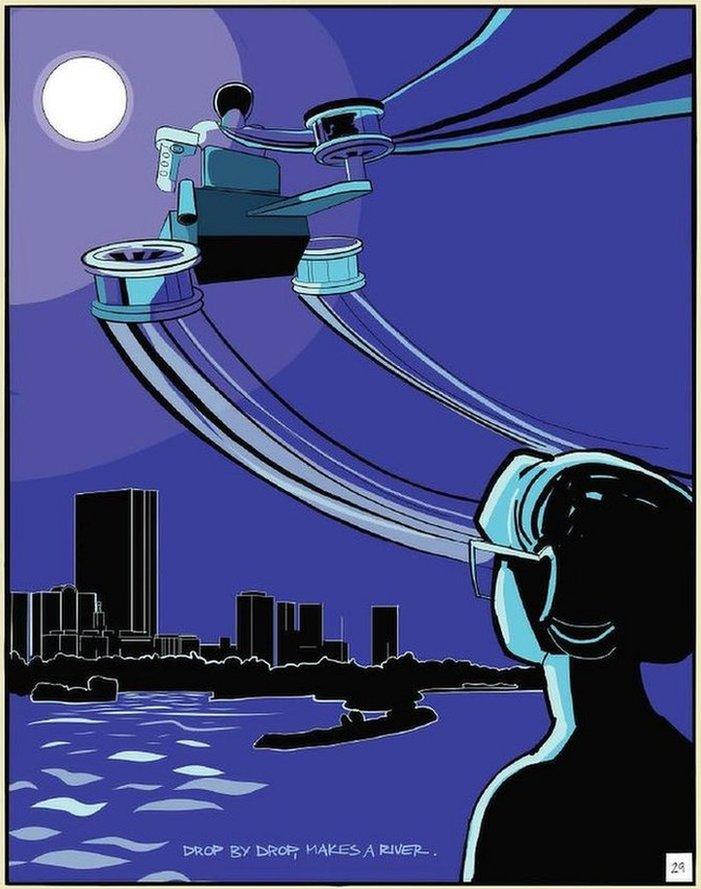

So I started designing my own invention that would allow me to have a cup-holder, a tripod to hold my camera, a canopy to keep the sun and rain off, and all of these different attachments that I wanted for my wheelchair - I called it the Key 2 Freedom.

It's 3D printable, magnetised, customisable and everything is controlled by the user. This is important because most companies make products that attach to the back of a wheelchair and which can't be controlled by the user.

Somehow the White House heard about it and I was invited to the 2015 White House Science Fair and presented to President Obama. I got a lot of publicity.

It turns out that not many similar products exist, so I decided I wanted to actually start a company that developed these products and take them to market. Several of my inventions are now patent pending.

During that period my mom took me to Boston Comic Con where they have superheroes and all these different comic characters - Spider Man, Iron Man - but no superheroes that represent the wheelchair community.

I thought: "This is the greatest country, how is it possible that they have no wheelchair superhero?"

Listen: The moment I decided to create a wheelchair superhero

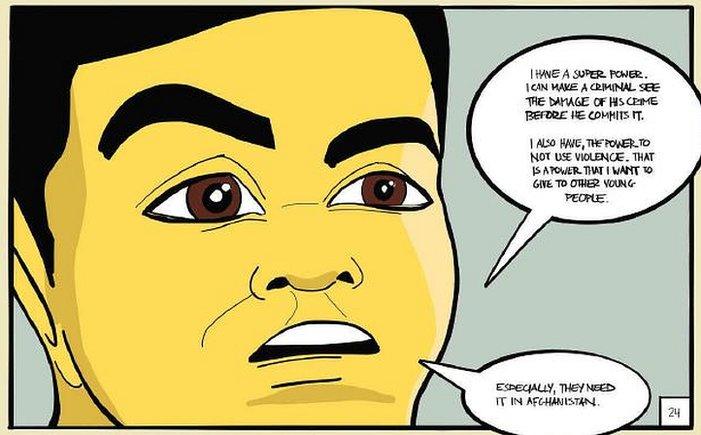

Well, I wasn't going to wait for Marvel to do it. I want to celebrate the powers and abilities that wheelchair users have, so I started to create a superhero called Wheelchair Man, external based on my own real-life story.

I write the stories and then I have an artist, Arielle Epstein, who is very talented, draw the images.

Wheelchair Man is a teenager, he's an immigrant and he's a Muslim. He's against hatred and he wants to end violence and make this world a better place. One of his main superpowers is that he can make criminals see the consequence of a crime before they have even committed it.

My plan is to develop a comic book series to inspire people with disabilities. There will be four other original superheroes - Wheelchair Woman, Wheelchair Girl, Wheelchair Boy and Captain Afghanistan - and all of them will be based on the real lives of wheelchair users from developing countries.

Our dream is to also eventually turn all of the stories into video games and movies.

I want to motivate people in wheelchairs, especially kids, to not give up on their dreams. Whatever they want to do they'll do it 10 times better than if they had their legs because the pain and struggle that we go through makes us stronger.

That's my message, that's Wheelchair Man's message, and that's the message behind all the superheroes that we will create.

When I came to the US my father started reaching out to me and I talked to him. He had remarried twice.

Unfortunately one of my brothers, Wakil, who had followed in my father's footsteps and joined the ANA, was blown up by the Taliban two years ago. He bled to death on his way to the hospital. My father left the army after that happened.

My other brother, Big, and my sister, Zara, are still with my father. I really want to go back there to meet Zara. She was very young and had just learned how to walk when I was hospitalised. Now she's about 15 years old. Every time I try to talk to her on the phone she starts crying and then I start crying.

I've asked my father why he left me. I said to him: "You left me when I needed you the most."

But he was realistic. He said: "If I had taken you home, you wouldn't be alive today. We didn't have the resources to take care of you, you wouldn't have been able to go to school and this opportunity to come to the US would never have happened."

I think he was right.

Mohammad Sayed was interviewed by Sarah McDermott and Matthew Bannister

All images courtesy of Mohammad Sayed and Rimpower

Listen to Mohammad Sayed speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.