The family that wouldn't let PTSD drive them apart

- Published

It's well known that soldiers can suffer from post-traumatic stress after their experiences on the battlefield - but the effect this has on their families is rarely discussed. Matthew Green describes how one woman was finally able to help her husband find effective treatment after he twice smashed up their home with an axe.

When his daughter Grace sank shin-deep into the mud at Merseyside's Crosby Beach, Keith Collard seemed surprisingly reluctant to wade to her rescue.

An imposing, taciturn man who had served 14 years in the army, Keith was normally fiercely protective of his family: so much so that he'd rig Grace up with a live microphone to keep track of her while she was playing outside their home near Bolton.

On that summer's day, with his daughter crying out for help, Keith seemed oddly absent. It was only later that he confessed to his wife, Toni, that the scene had reawakened his memories of the 1990-1991 Gulf War. To Keith, the black strands of seaweed trailed across the beach looked like tufts of human hair.

"If he goes on the sand he is convinced there are bodies under the sand," says Toni. "It's too much for him." With a rueful smile, she adds: "Seychelles — never going to happen."

In 2001, Keith was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition that can cause symptoms ranging from crippling anxiety and explosive anger to flashbacks and emotional numbing. With the right care, many survivors make good recoveries. Left untreated, people can grow so desperate that taking their own life starts to feel like the only way out.

Since the Iraq invasion in 2003, the Ministry of Defence has funded large-scale studies by the King's Centre for Military Health Research to determine the extent of PTSD and other mental ill health such as anxiety, depression and alcoholism in the forces.

Broadly, the results suggest that a minority of combat troops suffer from such conditions, but that they may be significantly more common than in the civilian population.

Far fewer resources have been devoted to assessing the impact of war on military families, some of whom are only now starting to confront the aftershocks of years of intense operations in Afghanistan. Thousands of others are still grappling with the legacies of the Falklands, Northern Ireland, Bosnia and other deployments most of the UK has long since forgotten.

As many of these families have discovered, the insidious symptoms of PTSD can corrode even the strongest relationships. Men and women who cannot switch off the vigilance and aggression that kept them alive in a war zone can seem to bear scant resemblance to the confident and resourceful soldiers their partners fell in love with.

Find out more

Listen to The Enemy Within, produced by Matthew Green and Eleanor McDowall, a Radio 3 documentary on the BBC iPlayer

In families with children, couples must weigh the agonising dilemma of whether to bear the pain of separation or stay together and do their best to shield sons and daughters from the volcanic atmosphere ruling their home. Some children or teenagers may themselves suffer anxiety or start self-harming — the effects of what psychologists call "secondary trauma".

"Either you divorce or you get help," says Toni. "There's an unwritten rule that I'm only here while he's getting treatment or he's stable. When a family and children are involved, that has to be a deal-breaker."

Like many military families confronting PTSD, Toni, Keith and 15-year-old Grace - who live in a quiet area with sweeping views of the West Pennine Moors - have taken years to reach the point where they feel comfortable in sharing their experiences publicly. They told me their story in the hope that it would shine a light on the private battles being fought by thousands of other families.

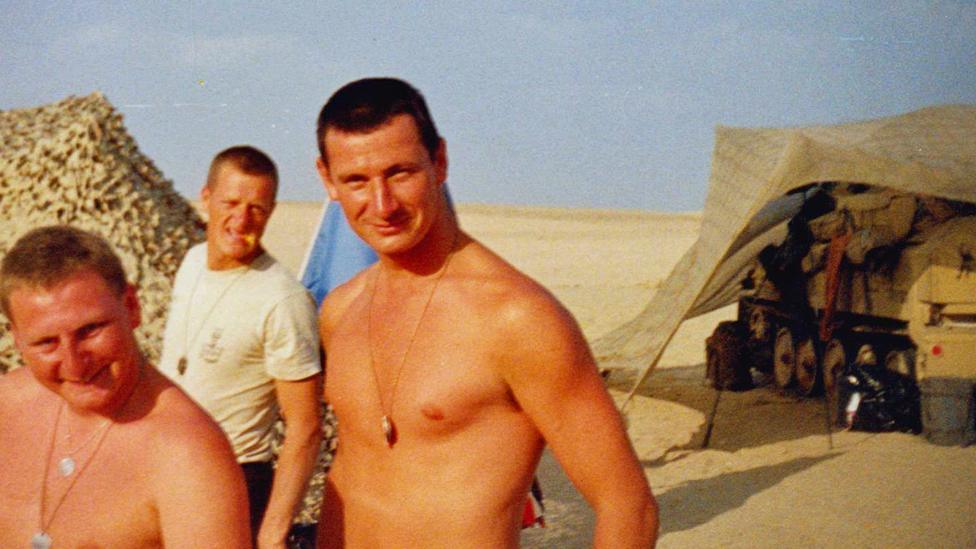

Keith (right) served in the 1990-91 Gulf War

When Toni and Keith first met, she had no idea of the turmoil bottled up inside him. Having left the army in 1993, he had ended up working as a security guard at a stationery shop in Manchester, where Toni was employed as a sales assistant. Toni noticed that he always seemed to be spoiling for a fight with shoplifters - he had boxed in the army - but he treated her like a perfect gentleman.

"At that point I didn't realise how bad Keith was," says Toni, 45, who went on to set up a successful ironing business in Bolton. "After a while you realise there are these lows that aren't right."

Keith, 53, says it took him years to suspect that he might be suffering from the after-effects of his tours overseas. "I just put it down to my personality: I got angry at things I shouldn't get angry at. I didn't know I was ill," he says. He had heard of PTSD, he says, but always associated it with Vietnam veterans and drug users.

Veterans with PTSD often suffer from a condition known as hyper-vigilance — meaning their brain and nervous systems react to everyday stresses on hometown streets or in the supermarket checkout queue with the kind of hair-trigger response more suited to a firefight.

Toni says Keith's permanent state of red alert, though it weighed heavily on the family, served him well in his job in the private security industry. He would go for days without sleeping then crash in their bedroom, sometimes refusing to leave the house for weeks.

Toni found her life began to revolve around managing her husband's moods and steering him away from triggers that rekindled his worst memories: the smell of burning rubber, the whirr of a helicopter or walking on sand. The overriding imperative of protecting Keith forced Toni to be especially strict with Grace and her son from a previous relationship.

"I've always had to be so firm, to make sure she toes the line because we can't have the kids acting up in a PTSD house," Toni says.

As a young child, Grace learned that if she wanted to speak to her father she had to knock on the bedroom door and open it very slowly. She had a ready-made excuse if her friends wanted to visit: Keith kept two highly trained Rottweilers named Zeus and Sky. The dogs did double duty, providing him with rare moments of solace and encouraging strangers to keep their distance.

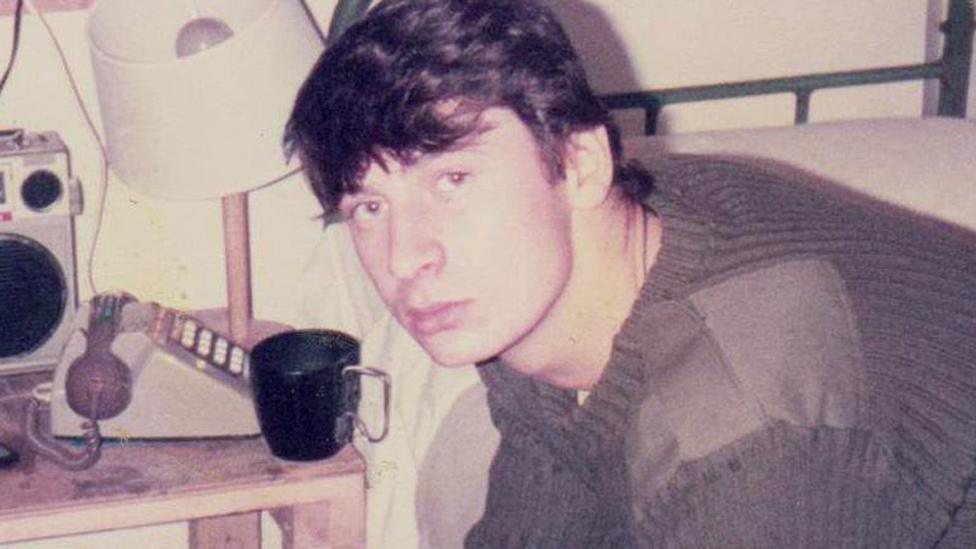

Grace: "The whole day would be based around how Dad was feeling"

"No matter what day I'd had at school, the whole day would be based around when I got home, how dad was feeling," says Grace. "He'd sit in his room for a week, and he wouldn't even come downstairs any more. I'd come upstairs and be like: 'How are you?' and he'd not really acknowledge me. I didn't know whether to apologise or to be angry at him."

In the early 2000s, Toni managed to persuade Keith to seek help and he went on to attend several two-week residential courses at Combat Stress, a veterans' mental health charity. As they learned more about PTSD, Toni and Keith did their best to help Grace make sense of his condition by calling it "Mr Grumpy".

"When he needs to be left alone, when he is quite aggressive, when he is rude, I used to take Grace away and say: 'Oh, it's Mr Grumpy, we need to give him some Daddy space,'" Toni says.

The stays at Combat Stress helped, but Keith still lived in fear of losing control of his anger. Experts believe that the difficulties some people with PTSD have in managing their aggression may be linked to changes in the brain that happen as a result of psychological trauma. Viewed from this perspective, far from being "all in the mind", the condition is as much a physical injury as a gunshot wound, albeit one buried inside the skull.

On one occasion, when Toni had managed to persuade Keith to go on a family holiday at a hotel in Turkey, he dropped Grace off at a kids' club. When he returned a few hours later to collect his daughter, she did not appear to be among the gaggle of youngsters. Gripped by panic, he started shouting at security to lock down the complex - his whole body snapping into what he calls "action-on" mode.

Toni was powerless to calm him down until Grace was discovered shortly afterwards in a nearby bathroom.

Other incidents had more serious consequences. Keith once became so furious that he grabbed an axe and began smashing up the house. Toni fled with the children until he came to his senses and called the police himself. He laid the axe on a table and opened the front door to find armed officers bearing riot shields.

"I've come home to armed response in the street," Toni says. "When the police have finally let me in, my bath panel has been kicked in and my loft hatch has been ripped out because they're looking for the bodies of my children and me, because they think that he's done something. How do you explain that to the children?

"The second time, he smashed up the house after we'd gone. Everything, lovely wooden furniture - gone. When I got home, the police were at the house and he was already in the back of a police van. And a lovely policeman came up to me and said: 'He doesn't need to be in a cell, he needs a hospital, doesn't he?' And I said: 'Yeah, he does.'

"So they took him to the hospital. The hospital put him in a taxi and sent him home because there was no crisis team on to help him.

"We received a call the next day saying: 'Did I want to be seen by the domestic violence unit?' and I said: 'No, I just want some help for my husband.'"

Help for those affected

In 2009, Toni reluctantly decided to give up her ironing business, which had grown to employ 13 people, because she was afraid to leave Keith by himself. She forged a second career as a self-employed actors' agent, so she wouldn't have to leave the house.

Toni says one of her greatest sources of solace came from joining a network of military carers called Combat PTSD Angels, one of a number of support groups that have mushroomed across the UK. Started six years ago, the organisation now has more than 350 members, who campaign for better services and offer comfort and advice to newcomers, who often do not know where to turn.

While Toni did eventually find an NHS mental health nurse who was able to help Keith, the strain began to tell on Grace. Late last year she suffered such severe bouts of anxiety and nausea that she began to miss school and was even forced temporarily to abandon her singing and acting classes - the only activities that had allowed her to push the tensions at home out of her mind.

"It felt like I was in a bubble, and everyone else was doing their own thing and I was isolated from it all," Grace says. "But it wasn't a nice little bubble - it was horrible."

Grace and Keith

Grace has since been feeling much better and, in calmer moments, the family is able to reflect on how their shared confrontation with PTSD has strengthened their bond. Keith acknowledges that however much he had wanted to protect his loved ones, he owes his life to Toni. By sharing his story for the first time, he hopes to encourage other ex-servicemen and women struggling as he once did to open up sooner.

"If you haven't got the support of family and friends when you're not in your right mind, you've got no chance of helping yourself," he says. "At first it was very embarrassing: I used to be a roughy-toughy squaddie, I'd fight anybody and do anything. I do find it difficult to accept it, but I will speak to anybody about it."

While Keith is still not entirely comfortable around sand, the family is feeling confident enough to attempt another holiday this summer, this time in Jersey.

"I think that I've been really lucky that he's always been willing to engage with some kind of treatment and get some help. That's the biggie," Toni says. "Your life changes and it comes with good and bad. There are things we can't do, but it's made him much more loveable."

Matthew Green is the author of Aftershock: Fighting War, Surviving Trauma And Finding Peace

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.