The city where murder is swept under the carpet

- Published

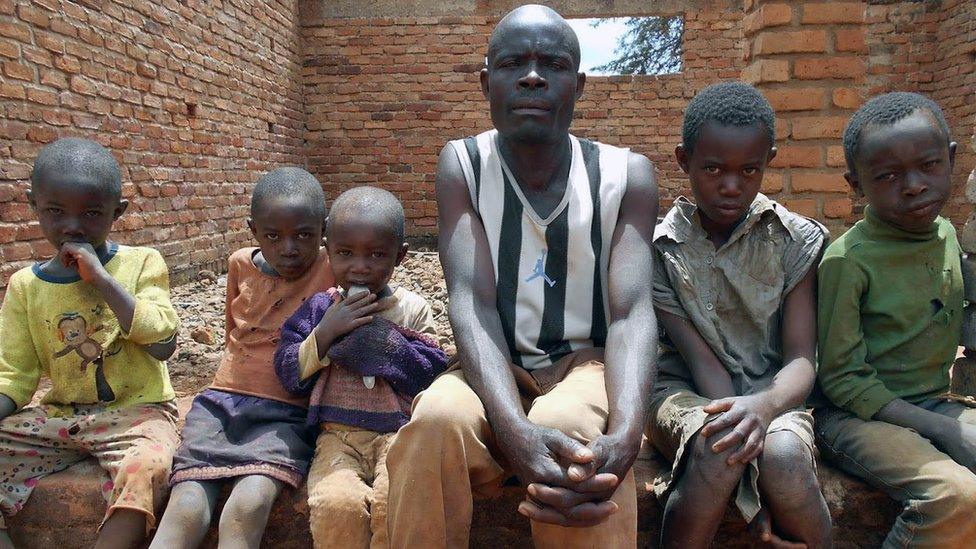

Raymond N'goma and his five children

In Malawi's newspapers, there is much talk of the need to tackle vigilante and mob justice. But the stories Peter Walker found suggest change is some way off.

In the dusty city of Mzuzu in northern Malawi, things seem to work. Mums, babies and squawking chickens pile on to a fragile network of tin-frame minibuses. Trade is thriving in the market. Here, merchants yell out the prices of rice, beans and eggs, engulfed by the odours of fresh fish and cheap rum.

But behind this facade is the constant presence of death.

Thanks to the scourges of drink driving, mob justice and endemic disease, there is a pungent smell of mortality. And with it, a police force seemingly oblivious, and apparently, ready to sweep murder under the carpet.

I already knew Malawi's judicial system needed an overhaul. But only after I spent one sun-drenched Saturday in the city's Zolozolo neighbourhood, did I realise how urgently.

Fifty-two-year-old Raymond N'goma lives in a home that is nothing more than brick walls and mounds of rubble. No roof. No doors.

Raymond, who earns 90p ($1.40) per day as a bicycle taxi driver, wears a black-and-white striped basketball vest, a neat moustache and a sad frown. His five children are dressed in clothes that are threadbare, outgrown and caked in dust. Their empty eyes are fixed on mine.

Raymond recalls how his second wife, who has now abandoned them, may have fatally poisoned his 18-year-old son from a previous marriage. She was held in police custody in 2011, but was returned to Raymond after four months. There was no trial and no conviction.

"I can't believe she poisoned him. I'm undecided. It was only doctors who checked the body and I've just left it in the past," he says, deadpan.

Sitting on the edge of a brick well, he hesitates, gazing wearily at nothing, when I ask him whether he killed his son. I laugh quietly at the absurdity of my own question. "I'm innocent. I can't poison my own son. It's complex," he answers.

In another case, 35-year-old Fiskani Chipeta, a market stallholder, was found unconscious outside a primary school in January. Two unknown men dumped her at the hospital. The same day, her house was burgled.

Fiskani's mother, Orlean, speaks some English, and weighs her words with tired concentration.

"I don't know who killed her, we can't know," she tells me. "But the death from killing, it's too much in Mzuzu. We are crying out for a miracle."

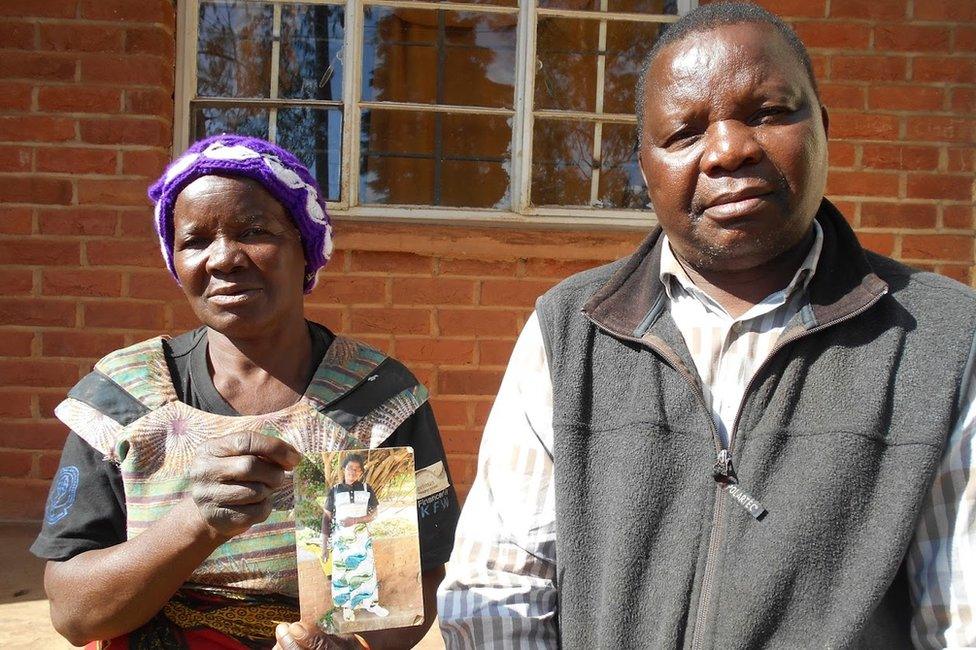

Orlean Mghogho and Tennyson Mghogho with a photograph of Fiskani Chipeta

Fiskani's parents-in-law didn't involve the police because they thought it a waste of time. Orlean's brother, Tennyson, adds: "My niece was left on the side of the road like a dead dog but there were no clues. If we went to the police they would just say: 'How do we find the suspect if there's no information?'"

Along Zolozolo's dusty main road, a woman swivels on her wooden chair, and points nervously to a nearby bungalow. "It happened here," she says.

Her friend Angelina Mkandawile, was beaten to death here last month. Extraordinarily, the suspect - her husband, Nogzani Hara - was kept in custody for just 48 hours. He was bailed after Angelina's burial.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

As we speak, he is in the Protestant church next door. "Everyone is complaining the police have done nothing," I'm told.

In a room dimly lit by the setting sun, village chief South Mfune tells me the story of friend and church volunteer Sarah Zgambo. Last month, Sarah's husband discovered her affair of four years. He beat her to death with a metal bar and threw her body into the botanical gardens.

A friend of his allegedly attacked Sarah's lover. Two suspects are in custody.

In this case at least, it seems the police did their job. But with tangible frustration, his clenched fists shaking, South tells me that his community are scared.

Sarah Zgambo

He says police fail to uphold confidentiality for victims and witnesses. And he tells me criminals will only be detained for one or two days. "People fear they will come back for them and kill them," he says.

As dusk settles, we meet five of Sarah's seven children. The eldest, 19-year-old Ruth, is composed, as her infant sister tugs on her ankle-length skirt. It's a typical African printed-cloth wrap, or chitenji, in vibrant yellows and blues.

It doesn't match her bleak state of mourning and even bleaker future. "When my mum is dead and my dad is in prison: it's very hard," she says.

Ruth was the day's most heart-rending example of someone on the receiving end of a failing judicial system. One that needs complete reform. Only then can my new friends feel safe in Mzuzu, the city where everything else seems to work.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.