Why it's hard to be a Kevin in France

- Published

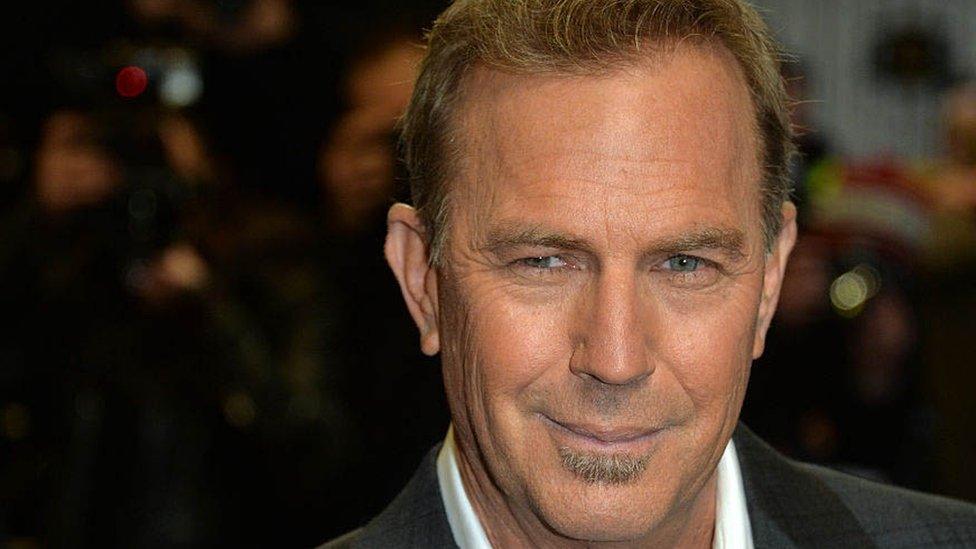

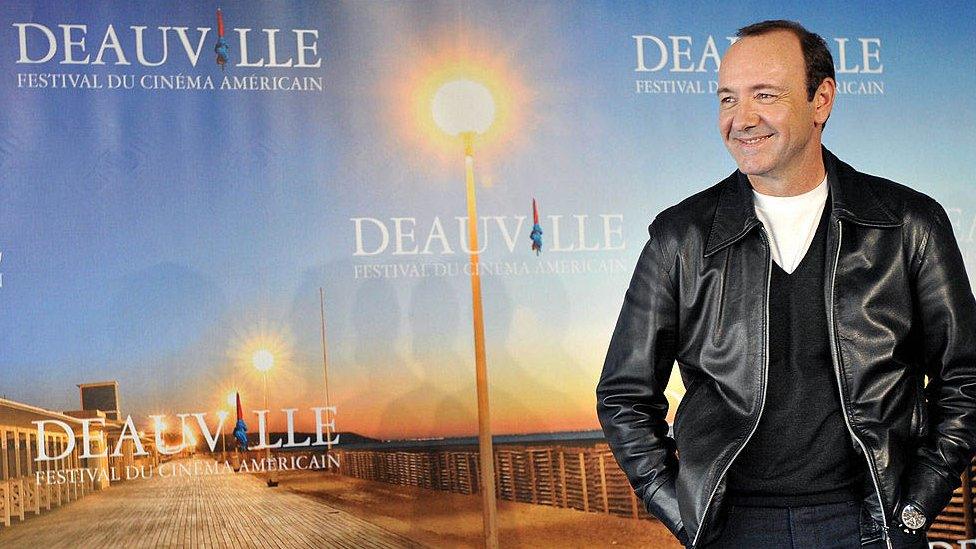

A movie star, oui... But still a Kevin

What happens when you have a name that seems perfectly reasonable in your home country, but raises a sympathetic smile when you're abroad? BBC Europe Correspondent Kevin Connolly has been finding out the hard way.

There is a theory called nominative determinism, much beloved of students of literature and other idlers. It holds that your character will come over time to match your name.

So if you are called Max Power or Chuck Handgrenade then you are predestined to life as a man of action - and if you're called Ray O'Sunshine or Sunny B Happy then you will be lovability incarnate.

I'd never expected to find myself touched by the theory personally, being equipped as I am with a wholly unremarkable name. I wasn't even given a middle initial on the utilitarian grounds that they're only useful to professional cricketers and American politicians.

That all changed when a colleague drew my attention to an article in a French magazine called The Curse of Kevin.

Its point was that, in the French-speaking world, that Christian name - my Christian name - more or less predestines you to being considered an idiot. And not necessarily a particularly lovable idiot either.

The city of lights. Not of Kevins

My Irish mother would have been mortified to hear this.

To her, Kevin was a respectable saint's name and added the music of alliteration to the prosaic sound of Connolly.

I've never been entirely persuaded myself - Kevin was a curmudgeonly hermit celebrated for pushing a woman who made overtures towards him into a bed of nettles.

If he were alive today I can't help thinking that Kevin would be receiving court-ordered counselling rather than the prayers of the faithful. But of course I had no say in the matter.

And the name wasn't always a curse in the Francophone world either.

When I lived in Paris in the 1990s, I wouldn't say it was enjoying a vogue exactly, but it was experiencing a kind of blip of recognition.

We even settled - in our office at least - on an agreed pronunciation of K'veen. It broke the rules of French phonetics a bit - it should surely be Ke-van - but people had at least heard of the name.

It was never quite clear why it suddenly surged briefly from obscurity, but we know that in 1991 a total of 14,087 French children were given the name Kevin - and no reason to doubt it was a winning ticket in the lottery of life.

We were never sure why. There were the Hollywood Kevins of course - Costner, Bacon and Spacey - but none of them seemed well-known enough individually to explain the phenomenon. Perhaps, we theorised, when you added them together they achieved a kind of critical mass - like a celebrity nuclear reaction.

We need to talk about Kevins

Rival theorists suggested that the name was copied from members of boy bands, or even, God forbid, from the American film Home Alone, in which the geeky super-child at the heart of the story is also called Kevin.

Anyway, our moment in the sun was brief indeed.

The number of new Kevins in France has slowed to a dreary trickle these days, with potential parents frightened off, perhaps, by the trenchant manner in which French sociologists analyse such matters.

Kevin, they say, simply was popular with the lower classes and Kevin was never well-perceived by his betters.

Kevin, in short, is an oik, shown in surveys to have as much as a 30% lower chance of being hired when compared with Philippe, or Jean-Luc or Vincent.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

The online discussion that followed the article did not contain, as it might in Britain or America, an angry rejection of this tendency to isolate and marginalise the Kevin, although it did include a handy list of other, equally cursed names, including Brian, Brandon, Jessica and Dylan. It didn't discuss whether this varies according to whether you're named after the American singer or the hippy rabbit from the Magic Roundabout.

Anyway, a novel has now been published in French which tells the story of how a young man improves his chances of being accepted into the intellectual salons of Paris by changing his name from Kevin to Alexandre.

I'm not sure my own disqualification from those salons was ever entirely down to my name but it all feels like a timely reminder of the exclusion which now appears to be part and parcel of the life of a Kevin in the Francophone world.

I'd like to say that I just don't understand it. But then, of course, that's the curse of nominative determinism. Anyone called Kevin is destined to not quite understand anything.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.