The place where children can be very unlucky with their names

- Published

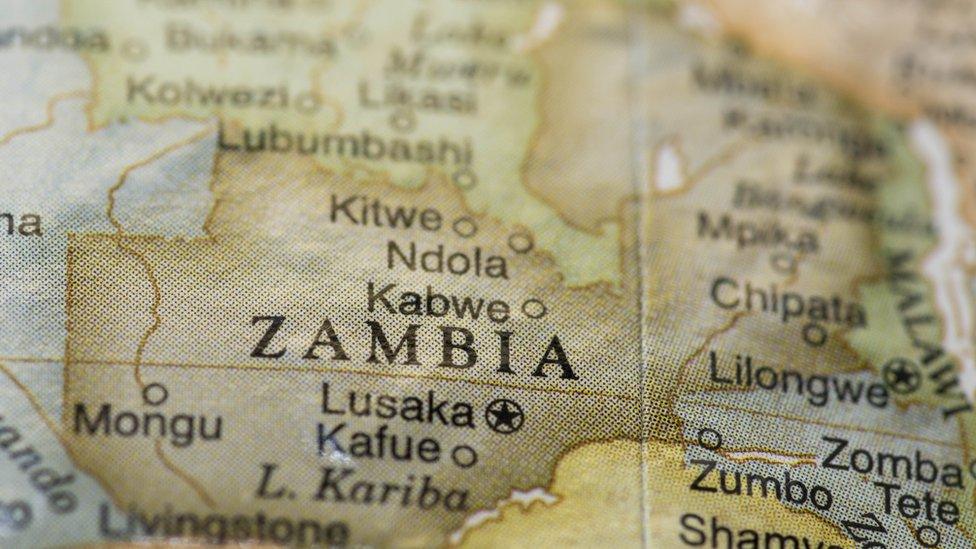

Spare a thought for those who are bestowed with troublesome names. That can happen anywhere, of course. But, in Zambia, Chris Haslam came across some very surprising choices.

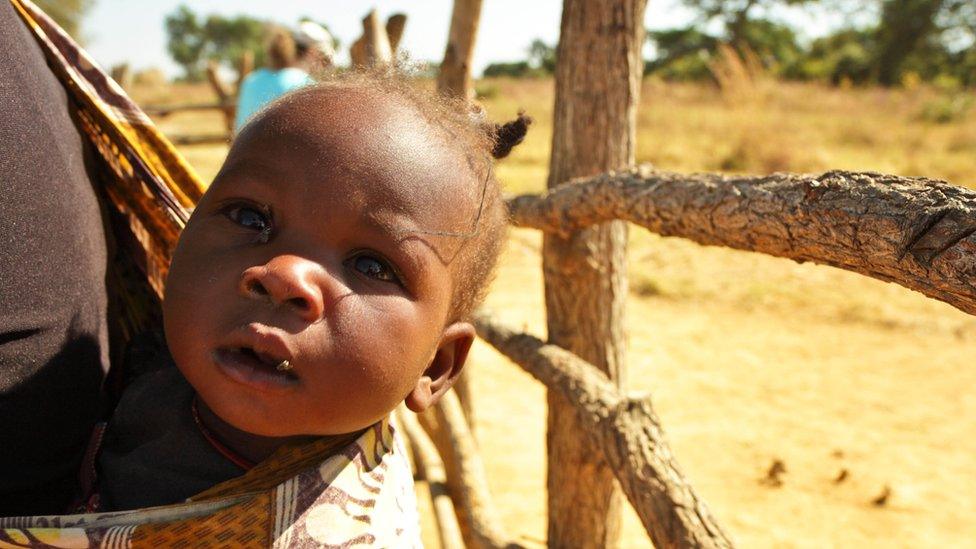

Under a darkening sky on a dusty, potholed track in eastern Zambia, a small boy is struggling to push a large, Chinese bicycle. Its handlebars, crossbar and panniers are stacked impossibly high with yellow jerry cans, firewood and a sack of rice. Because the boy needs both hands to keep the bike upright, he can't sweep the flies from his eyes. But this seven-year-old is labouring under a much heavier, but less visible burden.

His name is Mulangani. It's a Nguni word meaning "punish me". Or "he who must be punished", if you want to get formal. Who, I asked my driver Mavuto, would give their child such a horrible name?

"Maybe his grandfather, maybe the chief," he shrugged, explaining that across Zambia and neighbouring Zimbabwe, it is common for parents, especially in rural areas, to invite community elders to choose the name of a newborn.

"Sometimes the chief wants to punish the family," says Mavuto. "Or he may think this new child is too much for the family to bear."

Watching the boy's Sisyphean progress towards his distant home, that name suddenly seems disturbingly apt, but he's not the only one cursed with a dismal name. In later days, I meet Chilumba - "my brother's grave", Balaudye - "I will be eaten", Soca - "bad luck" and Chakufwa - "it is dead".

I also meet Daliso, whose name means "blessings" and Chikondi, which means "love". Maybe it's me, but they do seem happier.

"In African culture, there is a trend of naming children according to the circumstances surrounding their birth," says Clare Mulkenga-Chilambo, a care worker at SOS Children's Villages in Zambia. "It's good for those born at bright and merry moments but unfortunate for the others."

And there are a lot of others. HIV and Aids have ravaged Zambia, and although infection rates are now falling, 55,000 adults and 5,000 kids became infected in 2015. Countrywide, an estimated 380,000 children have been orphaned by Aids and 85,000 are living with HIV.

Ask Massiye, or "orphan", or Chisonis - "sadness", or the sad-eyed Chimwamsozi, whose name means "drinker of tears". Or nine-year-old Komasi, whose name means "kill him", and his little brother Komaniso, aka "kill him also".

"Most Zambians have several names," says Kangachepe Banda. His name means "well off" or "richness", and as a safari guide he's doing OK.

"You're talking about the first one. It's called the zina la bamkombo- or the name of the umbilical cord. After a birth, the mother and child hide away until the cord drops off. On that day, the baby is presented to family and neighbours, and the person honoured with choosing the name makes his decision."

Use of this name is supposed to be limited. It's supposed to be kept between the namer and the named - a dark reminder to the growing child that one person saw into his or her soul at birth.

The church, says Clare Mulenga-Chilambo, offers deliverance. "Most people turn to Christianity and on baptism, they are given Christian names," she says. "This gives them the opportunity to give up their traditional name, which is often seen as the cause of whatever misfortune they could have been facing in their lives".

But there are some here who see opting for the homogenised anonymity of John, James or Mary as a dereliction of tradition. Others feel that the names must be kept not just out of respect to elders but also as a guarantee of ancestral protection.

If the name maketh the man, then surely Zambia's notoriously grim prisons are full of unfortunates who've been saddled with names like Chidano, Mapenzi and Chananga - that's "hatred", "trouble" and "wrongdoer" respectively?

"It's possible," concurs Muvato. Growing up, he knew a kid called Chiheni, which translates as bad boy, or thug.

"He ran away from home when he was 12," he says. "He is in prison in South Africa for the attempted murder of a security guard."

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

Meanwhile, little Mulangani - he who must be punished - has scrounged a lift in the back of our pick-up to his home. It's a tin-roofed hut with a neat vegetable patch patrolled by bickering chickens and a dog called Imbwa. Which means "dog".

Sometime soon, says Mulangani, I'm going to be baptised. My new name will be Emanuel. It means God is with me.

He smiles.

He likes Emanuel.

As we drive away, there's a storm brewing in the west. The potholes are getting deeper and the clutch is playing up. As the first fat raindrops splatter the dusty windscreen, it suddenly strikes me that I haven't asked Mavuto what his name means.

He grimaces as he struggles to find third gear.

"It means problems," he says.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.