Dying in prison: Two women's stories

- Published

Jessica Whitchurch

The number of women who died in prison in England and Wales reached a record high of 22 last year, and more than half of them took their own lives, Prisons and Probation Ombudsman Nigel Newcomen reported this week.

"Behind the statistics are stories of avoidable tragedy," says Deborah Coles, director of the charity Inquest.

Most women who end up in prison have experienced a range of problems, such as addiction, mental illness, abusive relationships or homelessness - and if these problems had been addressed, Coles argues, things might have turned out differently.

Here are two of the stories behind the grim statistics of 2016.

Jessica Whitchurch

Jessica grew up in Nailsea near Bristol with her parents and three siblings, Ben - the oldest - Emma and Beth.

"We had a real rough childhood but we had good times as well," says Ben.

Jessica Whitchurch and her sisters Emma and Beth

Together the family enjoyed holidays abroad in France, Spain and Greece. And there were other happy family occasions - birthdays and Christmases, for example: the two would overlap because Jessica's birthday was on Boxing Day.

But they all had spells in foster care - both parents struggled with alcohol and would fight. One day their father disappeared to live abroad, and in 2002 their mother died after a long battle with addiction to prescription drugs and alcohol.

Ben was an adult by then, but the three girls were sent to different foster homes. Beth, the youngest, was 12, Emma had just turned 15 and Jess was 17.

"Out of us four kids, with everything we went through, I suppose one of us had to take the wrong turn," says Emma.

Jessica struggled to find a job and would get into relationships with abusive and violent men. Things spiralled. She began to drink and take drugs - heroin, crack, anything - and turned to shoplifting to pay for them.

Her life became chaotic and her siblings would struggle to keep track of where she was and with whom.

"Jess was free-spirited, fun-loving and creative. She could speak German and Spanish," remembers Ben. "But she was also very vulnerable and a lot of her prison sentences were to do with her violent relationships with men." According to the Prison Reform Trust, 46% of women in jail report having suffered a history of domestic abuse.

Ben explains that she had wanted to be a youth worker - a job she would have been good at - but criminal convictions made that difficult.

"Jess was a good person, she was the kindest person. She used to do anything for anybody, but drugs and alcohol took over," says Beth.

By the time their sister was sentenced for the final time, she'd been in Eastwood Park prison in Gloucestershire at least seven times. Beth and Emma spent many hours visiting her there over the course of four or five years.

"We'd get a call from her in prison - 'I'm OK,' she'd say and then we'd go and see her," Beth says.

When she died in May last year she was serving her longest-ever sentence - 16 months for street robbery.

"Jess seemed like she was thinking about the future - she was talking about going into rehab when she got out and she wanted to get into counselling," says Beth, who visited her three days before her death.

While in prison she was diagnosed with a personality disorder and severe depression.

"They finally know what's wrong with me," she wrote in a letter to her family in March. In prison she'd fill her free time with crocheting, knitting and drawing. Bristol charity one25 would send her crafts, books and magazines - they had supported Jessica while she was on and off the streets too.

"She made us some beautiful cards and she knitted a doll which she gave to my daughter the last time we visited her," says Beth.

Prison visits were normally upbeat. "We'd spend it laughing, she was so funny," Beth remembers.

Jessica was keen to catch up on news about life beyond the confines of the prison. But she also complained that she was being bullied by other inmates, say her siblings. She had been placed on a care plan known as ACCT, used for those thought to be at risk of self-harm or suicide.

When the 31-year-old killed herself she only had two months left to go on her sentence. On 20 May, two days after being rushed to hospital, she was pronounced brain-dead and her life support was turned off.

She left behind a handmade birthday card for one of her nieces and a note that said: "To Em, Beth and Ben - I'm really sorry, I had to do this. Be strong. I'm with mum and dad now."

Jessica was one of three women to kill themselves at Eastwood Park in 2016.

When her siblings saw her body, it was covered with scars resulting from self-harm.

"Jess should not have been in prison, she should have been in a mental health facility," says Emma. "She needed peace. That root of all evil needed to be found, and putting her in prison just tormented her."

Charlotte Nokes

Charlotte grew up on Hayling Island near Portsmouth and was the middle child of three. "When she was really little, she was an absolute darling," says her mother, Sue. "She was very clever and she could talk anyone round - even the police when she got older. She endeared herself to people."

"She was so funny, and fiercely loyal - but she was also a very troubled person," says her older sister Rachel, describing some of her sister's aggressive, erratic behaviour.

Her family now know that Charlotte had a severe personality disorder - it was diagnosed as an adult. "As a child she was very sneaky and was never scared of anything; we all just thought she was hard work - we didn't know she had real mental health problems," says Sue.

Charlotte Nokes as a child

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when her life began to take the turn that it did, but at about 12, Charlotte began taking drugs and drinking.

"Charlotte was gay and where we lived had a very small-town mentality and she had a lot of trouble with people - she would walk down the road and get beaten up," her mother says. She started carrying a knife and got a teardrop tattoo on her face - often the symbol of a killer or gang member.

At 18 she moved in with friends in Portsmouth and began stealing to feed her drug addiction, which by that time had graduated from cannabis to crack cocaine and heroin. Her life became increasingly chaotic. "Her whole day became about finding money to buy drugs," says her mother. "It didn't matter what we did or didn't do, we made things worse; we were often the trigger."

Charlotte's record of offences begins with shoplifting, drug possession, parking fines. By the time she was sentenced for the final time, she had more than 50 convictions for petty offences, says her mother Sue. Prison wasn't working and had become a revolving door.

Are you affected by this?

Samaritans provides emotional support, 24 hours a day for people who are experiencing feelings of distress or thoughts of suicide

Its number is 116 123

Rethink Mental Illness has more than 200 mental health services and 150 support groups across England

Its number is 0300 5000 927

On her 30th birthday, 27 October 2007, Charlotte was supposed to have gone to the cinema with her mother to celebrate. Instead she was arrested for street robbery and carrying a bladed weapon. Inebriated, she'd asked a passer-by for 40p and had staggered towards the woman with a knife. Fearing she might get stabbed the woman ran across the road and was later taken to hospital with chest pains. Charlotte was arrested close by, waving the knife above her head.

She was convicted of street robbery, in January 2008. By this time her mother had given up on going to sentencings - she had been to so many. Charlotte was handed an indeterminate sentence for public protection - known as an IPP sentence. It carried a minimum of 15 months and her freedom would depend on passing probation reviews. When Charlotte died, she had been in prison for eight and a half years.

Her family say the IPP sentence she'd been handed by the judge gave her no hope - she struggled to cope and would grow more volatile with each rejection of her parole. Charlotte would self-harm and told her mother about attempts to kill herself. Like Jessica, she was also on the ACCT care plan.

"She had black moods she just couldn't get out of," says her sister, Rachel. "She had done things she wasn't happy about and it always tormented her."

This didn't always show.

"She used to phone me at work - sometimes she'd phone once a month, sometimes every day. Sometimes she was crying, sometimes laughing, sometimes you couldn't get her off the phone," says her mother.

At other times she would not want visits or calls from anyone.

Prisoners serving IPPs have one of the highest rates of self-harm. On average each year there are 550 incidents per 1,000 people serving an indeterminate sentence, compared with 324 per 1,000 for those on determinate sentences, according to the Prison Reform Trust (PRT). Although IPP sentences were abolished in 2012 more than 3,000 people are still serving these sentences, the PRT says, and 84% of them have already served their minimum tariff.

The one thing which Charlotte found rewarding in prison, and would calm her down, was painting.

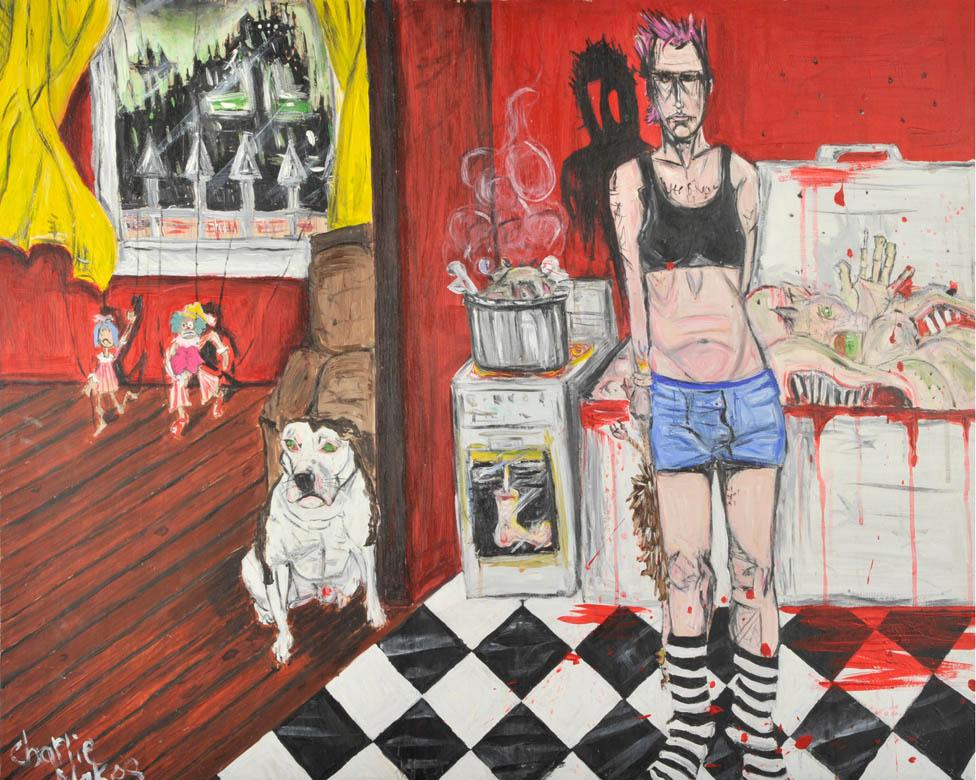

Nightmare Mise-en-Scene by Charlottle Nokes

"She would paint on anything she could get her hands on - bits of cardboard, doors, signs," says her mother.

She was allowed to paint murals all around Peterborough prison and would take commissions from the other women, decorating their cells for them and making birthday cards for their children on the outside.

"She always cared and looked after other people - she just couldn't do the same for herself," says her mother.

Charlotte got support from criminal justice charities such as Women in Prison and the Michael Varah Memorial foundation and her work was exhibited by the Koestler Trust.

"By the end I couldn't afford to even buy her paintings," says her mother. "Things were really taking off for her and her mentors expected great things."

She had even been offered a scholarship to the esteemed Central St Martins art school on her release.

But the thing which boosted Charlotte the most was the prospect of being transferred from HMP Peterborough to a secure psychiatric unit, say her family. It was all to be settled at her next parole hearing, and this made her happier than she had been for a very long time, says her mother.

"She had things to look forward to, she thought she'd be looked after properly and get the help she needed," she says.

But at breakfast on 23 July 2016, the lifers' wing for women in HMP Peterborough went into lockdown. The women serving sentences there knew that they were being kept in their cells because something bad had happened.

They initiated their own roll call, one by one they shouted their names through the hatches in their doors. When it was Charlotte's turn, silence. The 38-year-old had been found dead, sitting up in bed in her cell by prison staff. Charlotte's family say it is suspected she died from a strain on the heart.

Of the 22 women who died in prison last year, her death is one of the three that are yet to be classified by Inquest. No date has yet been set for the coroner's inquest.

"I don't know if her life could have been saved, but I know that prison isn't where she should have died," says Sue. "But we have memories - we have more than some people, and we'd like Charlotte to be remembered through her art."

The Corston Report

Alarm over the number of women dying in prison - six in one prison alone in a 13-month period - gave rise to the Corston Report, external, published 10 years ago this month.

In it, Baroness Jean Corston called for women's prisons to be completely dismantled over a 10-year period in favour of small custodial units. The demand was rejected by the Labour government at the time, but has since been adopted by the Scottish government.

The trigger was the death of six women in Cheshire's Styal prison over a 13-month period in 2002-3.

Corston noted that most women who go to prison have not committed a violent crime - the Prison Reform Trust says 85% have been sentenced for a non-violent offence, compared with 70% of male prisoners - and argued that in such cases they should not receive custodial sentences at all. Instead they should be referred to "women's centres" - support and supervision centres in the community - to receive help for problems such as addiction, mental illness, homelessness and domestic violence.

The custodial units used for the minority of women considered dangerous should also emphasise therapeutic care, Corston suggested, and should be located in places that are easier for families to visit - in city centres rather than isolated rural areas.

Corston made a total of 43 recommendations and 40 were accepted by government. But it's not only campaigners who argue that progress has been limited.

"The sweeping whole-system reform envisaged has yet to be delivered," writes Prison and Probation Ombudsman Nigel Newcomen in his bulletin on female prison suicide, external this week.

While some women's centres have been opened, their work has been frustrated by a failure to invest in mental health services, the closure of domestic violence refuges due to funding cuts and a worsening housing crisis, argues Claire Cain of the charity Women in Prison.

"Ten years after the Corston Report we are seeing the same vulnerable women put in prison and the same vulnerable women dying," says Deborah Coles of Inquest.

"We continue to see the prison system as a panacea for all social ills, but it isn't working because we see women return to prison time and again. It is a revolving door."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.