The couple who want to rebuild their shattered city

- Published

Someday, what seems like Syria's forever war will end. Then the focus will shift to rebuilding a country shredded and scarred by conflict. A husband and wife, both architects, who witnessed their city's devastation are already thinking about how to restore it.

"It's not easy to rise from the ruins, it's not easy," reflects Marwa al-Sabouni.

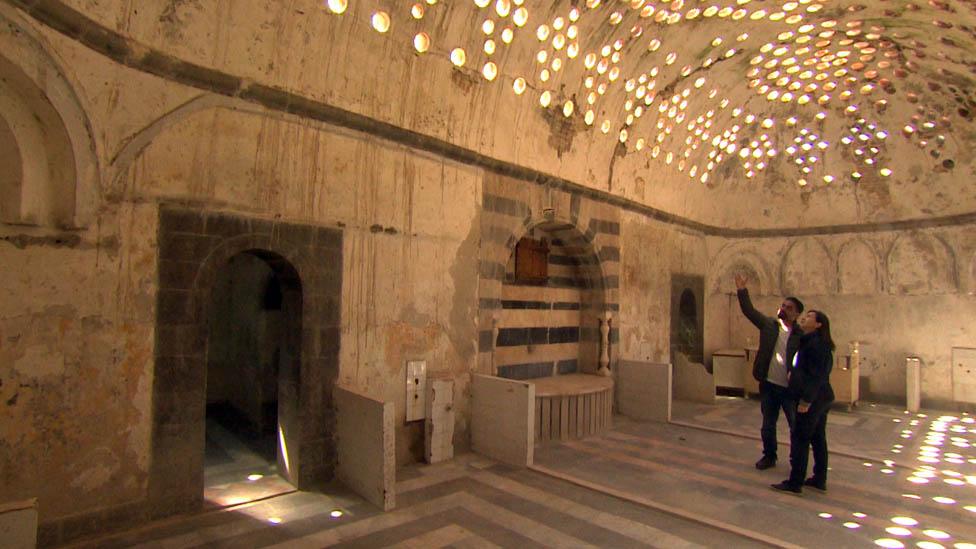

We're standing in the cool dark depths of a hammam - a public bath dating back to Roman times in the old quarter of Homs. Its thick stone walls are now rough blotches of black and brown, dappled by shafts of light streaming through holes in a domed ceiling designed to draw light into this ancient warren.

The history within these walls is even darker.

"This was a major battleground," Sabouni explains as we walk through the hammam's main chamber, with what remains of a water fountain at its centre.

The debris of recent battles has been slowly cleared since two years of fierce clashes in the Old City area ended in 2014 when the government took back what had been a rebel-held enclave of Syria's third city.

"So many of us didn't even know this beautiful hammam, and so many other parts of our heritage, existed before the war," Sabouni says.

"It was neglected and then destroyed before we had to chance to know it."

Sabouni has taken me on a walk to illustrate some of the main ideas in her acclaimed book, The Battle for Home. An evocative memoir of her family's experience of living through a punishing war in their city, it's also an architect's vision of how to rebuild Syria to help mend its wounds and avoid errors of the past.

One of her biggest allies is fellow architect Ghassan Jansiz - who happens to be her husband. Their ideas about architecture brought them together as students.

They remained with their two young children in a city which saw some of the first protests and the most vicious fighting of the war.

This 2,000-year-old hammam is our first stop on Sabouni's itinerary as we set out to explore the souk, a sprawling market that was once the vibrant heart of the Old City.

Its labyrinth of alleyways is still largely deserted with most shops shuttered, or shattered by the gunfire and explosions.

Syria's destructive conflict has been fuelled by many faultlines. Sabouni says architecture is one of them.

"Of course, I'm not saying that architecture is the only reason for the war, but in a very real way it accelerated and perpetuated the conflict," she explains.

Her book chronicles the rise, over the past century, of soulless tower blocks and urban sprawls that effectively created sectarian ghettos and eroded shared public spaces which had long shaped Syrian society. Sabouni sees the built environment as a crucible for the frictions that led to civil war.

A meander through Homs's old market is also a journey further back in time, through thousands of years of Syrian history and successive empires that left their mark. In this rich story, Sabouni finds lessons for a more inspired and inclusive way of living.

Marwa al-Sabouni with Lyse Doucet

"Certain architectural elements from different eras are all incorporated within the same structures and they don't cancel each other out," she explains as she leads me to what she calls a "hidden house."

A long dimly lit corridor leads into an exquisite courtyard with leafy fruit trees dotted with oranges. A sudden burst of bright colour surprises, as a small symbol of renewal.

"You see, this is what I talk about in the book," Sabouni exclaims.

"We had something very beautiful, very ancient and very harmonious interwoven in our lives, in our daily lives," she says, making her point that Syria's precious world heritage lies not only in famed sites such as the Roman ruins of Palmyra, but in its everyday social fabric.

"We vandalised a lot of it, and we mistreated a lot of it, so maybe we have the chance to start over now."

In another corner of the market, Jansiz shows me another hammam dating from the days of the Ottoman empire.

Its vaulted ceilings with intricate patterns of holes creates a dance of circles of light on the stone walls and floor.

But it's a pattern of light caused by damage rather than design which provides a small example of how to build from the ruins. The market's metal roofs - punctured by bullets and shrapnel - inspired Jansiz's work on the first rebuilding project in the Old City funded by the UN Development Programme (UNDP).

On the day we visit, the project is a hive of activity. Workmen in blue overalls are putting the finishing touches on the new patterned screen now arching over the alleyway at one of the market's main entrances.

"Rebuilding is not just about stones," explains Jansiz, who was the lead architect on the first phase of the project.

"This market wasn't just a place to sell and buy stuff. It was also a social hub where people from all social and religious groups would spend time with each other."

A roof designed by Ghassan Jansiz

Both Jansiz and Sabouni underline how the damage to Syria's social fabric is far deeper even than the endless ruins in pulverised neighbourhoods.

"All the workers you see around you are from Homs," Jansiz adds. "They understand this city and understand its pain."

The long arcades of shuttered shops bear silent testimony to this aching sense of loss. Only about 30 out of nearly 5,000 have reopened.

Some shopkeepers can't afford to rebuild, or await electricity and other services. Some sided with the rebels and were forced to flee, and are now unable or unwilling to return.

With still no end in sight to this war, major Western donors still resist putting money for reconstruction into areas now back in government hands.

"So far we're only focusing on limited rebuilding to provide some support and a bit of hope," UNDP Country Director Samuel Rizk tells me.

But the EU recently began to carefully raise the prospect of reconstruction funds, if and when a hesitant process of political talks with the opposition makes significant progress.

And a Chinese delegation was in Damascus this week to discuss future investments in industries and infrastructure.

There are already hints of conflicts to come over contracts and concepts for a post-war Syria.

Even the first phase of this small project to rebuild a roof in the Old City ended up being clouded by disagreements.

Sabouni believes Syrians must begin to imagine a different future.

"It may sound so sophisticated or a luxury to talk about architecture," she says. "But if we don't think about it, I think we will miss the chance to rebuild it in the right way."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.