Would cash prizes make you more likely to vote?

- Published

As the UK heads towards its third big national vote in three years, there are fears that people won't bother turning out - with apathy particularly strong among the young.

It's a problem across Western democracies. In last week's French presidential race, turn-out fell, external, and in the US last year, only slightly more than half of people eligible to vote cast a ballot for a presidential candidate. In Britain, turn-out has hovered at around 65% for the last two general elections, way down on figures from the previous century.

To combat the problem, several US cities are experimenting with a controversial idea: offering cash prizes to the electorate, in a bid to lure them out to vote.

In these schemes, people casting votes are added to a lottery, with big money prizes for a lucky few.

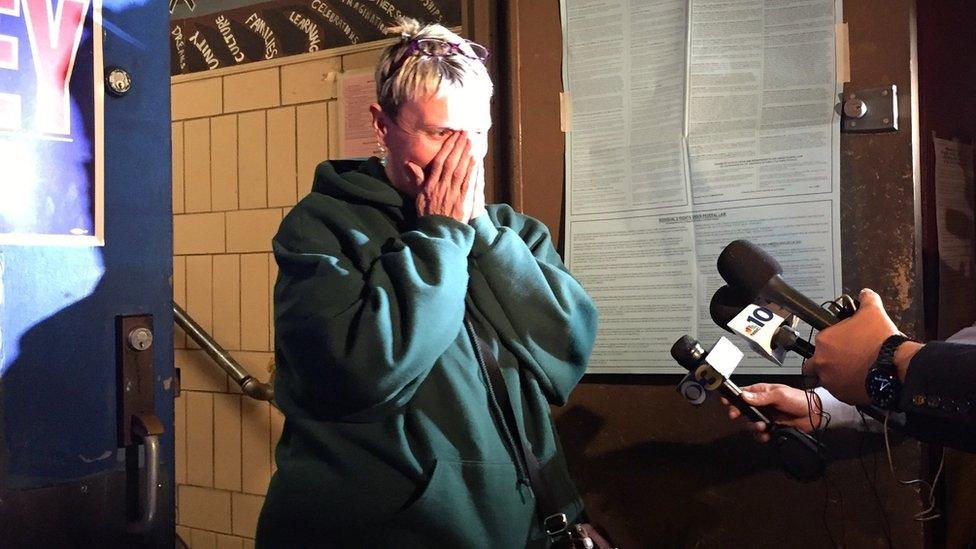

Bridget Conroy Varnis, a 52-year-old voter from Philadelphia, picked up a cheque for $10,000 after voting in a local election. "I was shaking, nervous, surprised, and I felt blessed too," she told us. She was presented with the award right there at the polling station. Camera bulbs flashed as a huge dummy cheque was handed over.

Bridget Conroy Varnis after winning at the polling station

Ray La Raja is a political scientist at the University of Massachusetts, and one of the academics behind the idea. He says that as well as boosting turn-out, voter lotteries can help counter traditional problems with the system.

The older, richer, whiter and more highly educated you are, the more likely you are to vote in the US, he explains. "If you go to a system in which you rely heavily on individual resources such as education, money, proximity to voting booth, you're going to get systematic bias in who turns out."

A similar lottery - the first of its kind - was run in Los Angeles by Antonio Gonzalez, president of the Southwest Voter Education Registration project. He was also troubled by the pattern that Ray La Raja highlights, and he wanted to encourage more people from Latino communities to vote.

"We called it 'Voteria' to rhyme with 'Loteria' because that's a big deal in the Mexican and Central American community here. We wanted the branding to catch on," he explains. The lucky winner got $25,000.

The vote in question was for a local school board trustee, and indeed turn-out increased from 9% to 10%. The change wasn't dramatic, but as Gonzalez points out, the campaign had a minimal marketing campaign. An exit poll found that among voters who had heard of the scheme, around half said it was their reason for coming out to vote.

In Britain, another trial was conducted, external to see if a lottery could boost the number of people registered to vote - again with encouraging results.

However, while lotteries have shown signs they can boost both turn-out and registration, many have questioned the ethics of using cash incentives to persuade people to vote.

World Hacks is a new BBC team that aims to report on solutions being tried out, rather than focussing only on global problems.

We meet the people fixing the world.

Handing out money in return for voting is actually illegal in most US states, thanks to anti-bribery laws designed to prevent powerful interests from buying up votes.

Voting lotteries appear to be a loophole, because they award random prizes rather than direct payments to each voter. But ultimately, it is still a legal grey area that needs to be tested state by state, and nation by nation.

There are also suggestions that offering financial incentives can actually reduce participation in certain activities.

In an experiment with blood donors, for example, offering payment in exchange for blood actually prompted some regular donors to stop taking part. Cash payments had turned what the donors saw as a civic duty into a financial transaction, which became far less appealing.

And on the other hand you might encounter the opposite problem: attracting people who hadn't been voters before, but who didn't take the process of selection seriously.

Barry Schwartz, a psychologist at Swarthmore College in the US, is sceptical about offering prizes for voting. There are no incentives clever enough to replace the basic idea of doing the right thing, he says.

"If you had 80% turnout, and half the people didn't know what they were voting for, you wouldn't think the problem had gone away. You've got the same problem," Schwartz argues.

For Antonio Gonzalez, the president of the Southwest Voter Education Registration project, the process isn't quite so simple. Their big idea is that encouraging people to vote - even by offering material incentives - will encourage them to become more clued up about politics in the long term.

And the alternative is the system we have now, where turnout is skewed in favour of people who are already more privileged members of society. A sort of "dictatorship of the informed", as Gonzalez puts it.

Clearly, the idea is a controversial one. Voter lotteries have some way to go before being accepted as a practical, and ethical, solution to the problem of low voter turnout.

But after their initial success, two more voter lotteries will take place in Philadelphia this year.

And if - as is widely expected - huge swathes of young people fail to head to the polling booth at the UK's general election on 8 June, it could be an idea that begins to attract more attention.

Listen to BBC World Hacks on the World Service or listen back on the iPlayer.

- Published16 March 2017

- Published27 February 2017

- Published2 December 2016

- Published31 October 2016

- Published9 January 2017