Spring-cleaning India's most magnificent tent

- Published

Rajasthan's Royal Red Tent is as tall as a double-decker bus, made from silk, velvet and gold - and it's getting its first proper clean in more than three centuries, says Melissa Van Der Klugt.

High up on the ramparts of Mehrangarh, in one of Rajasthan's most famous forts - one of the most visited in India - a small team is dusting down a large tent.

Each section is so big that the three conservationists - dressed in neat white overalls and equipped with pocketfuls of soft brushes - must clamber around on tables and chairs. "The priority is the object," says one, pointing to the elaborate design of lotus flowers stitched in solid gold thread.

For this is no ordinary tent - but one that excites huge interest and controversy in India. It was once thought to have been the home of Shah Jahan, the great 17th-Century Mughal emperor who built the Taj Mahal.

His nomadic ancestors rode down from Central Asia and Afghanistan to conquer swathes of India - and this was his "travelling palace".

Made in imperial workshops from exquisite red silk velvet and gold, it stands when unfurled at 4m (13ft) - as high as a London double-decker bus. It's known as the Lal Dera, or the Shahi Lal Dera - the Royal Red Tent.

And it's being given its first proper spring clean in 350 years.

"There is no surviving piece like it in India or anywhere," says Karni Singh Jasol, the director of the fort's archive in Jodhpur. "The idea was that it had to have all the luxury of a painted stone palace."

Shah Jahan was nicknamed "the Builder of the Marvels" - he ordered up some of Delhi and Agra's finest monuments - but spent most of his three decades in power on military campaigns.

Shah Jahan, depicted circa 1625

One hundred elephants, 500 camels, 400 carts and teams of bearers were once needed to carry the emperor's camping equipment as he roved across plains and jungles with tens of thousands of horsemen.

"In his tent," says Jasol, "there would be cushions and bolsters and a bed, and objects like hookahs or wine flasks and jewellery cases."

Porters carried porcelain for the emperor's table. He was said to travel at a leisurely 10 to 12 miles (15 to 18km) a day, pausing to hunt cheetah or deer.

The Mughals were used to erecting these temporary cities, says Jasol. Shah Jahan's great-great grandfather, the first emperor, Babur, who arrived in India from Afghanistan, once boasted he had never spent any two Ramadans in the same place.

One encampment contained so many scribes, harems, court officials and workshops churning out leather goods and artwork that an astounded British ambassador wrote that it must be the same size as Elizabethan London.

The Rent Tent was believed to have been looted during a battle, whose victors, the rulers of Jodhpur, took it back to their fort, Mehrangarh, in the sun-baked Thar desert. And there it has remained.

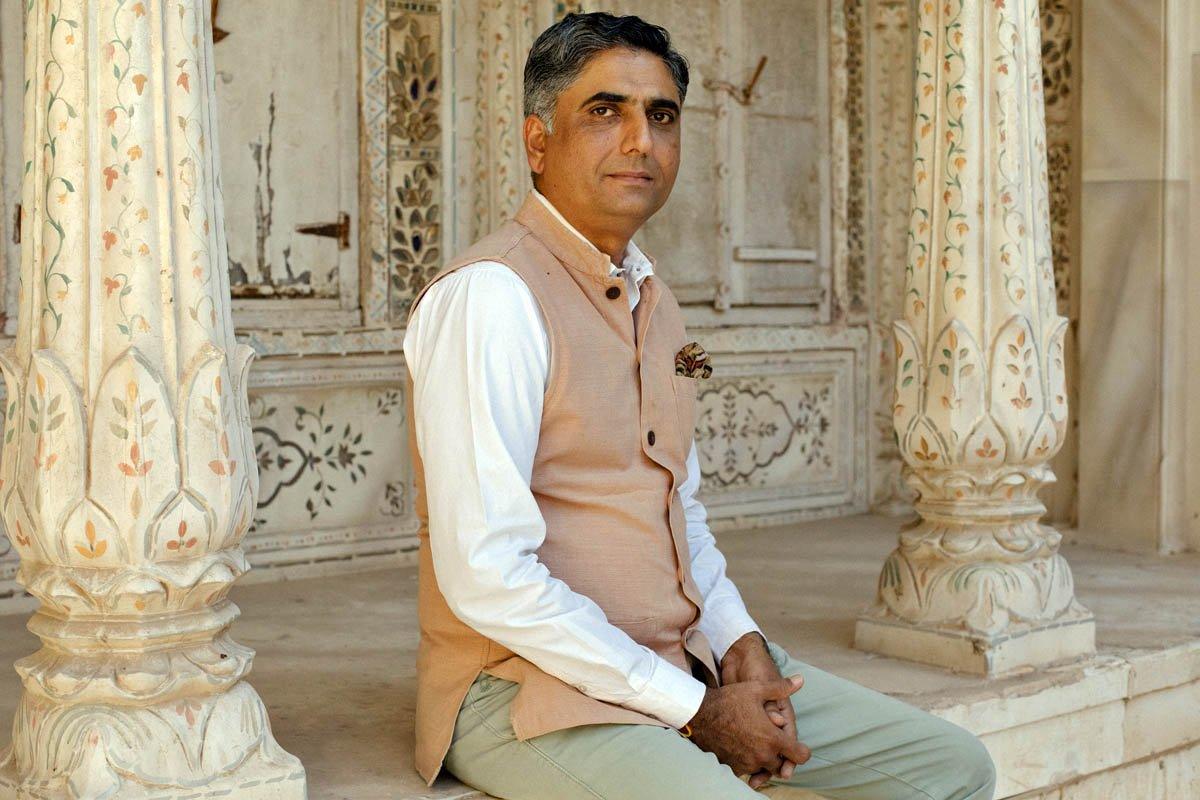

Immaculately dressed in a Nehru waistcoat and cravat, Jasol now presides over the vaulted archives within Mehrangarh's thick stone walls. They house thousands of precious artefacts and documents, often requested for exhibition abroad.

Art historians now argue over whether the Red Tent belonged to Shah Jahan or his ruthless son, Aurangzeb - who put his own father under house arrest.

"But it is still our rarest and most prized object," says Jasol. All other Mughal tents of the same size have been dismantled and the pieces scattered.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

It began to show its age. "It was on display in one of the galleries here," says Jasol. "But every morning the staff would see a sort of gold dust… There was a lot of stress on the velvet and the brocade so we put it into storage to rest."

Its conservation is part of a bigger project to revamp the museum to appeal to India's booming domestic tourist market.

When Mehrangarh opened as a museum in 1974, most visitors were British or American. "All the rooms had been locked up and only the temples had been active," recalls Jasol. "I remember the first director describing how it was full of bats and bat droppings."

Now Indian visitors - curious about their history - have overtaken foreigners.

The Red Tent's big clean is being carried out by team of three conservators. "The effort that went into making it shows the dedication to the emperor," says one, Shakshi Gupta, peering at the fabric through a magnifying glass.

"Velvet these days might last just 20 years if you are lucky. This kind of labour and intricate weaving by hand would be too expensive."

The women are living in rooms at the fort for the next year. "It was a little spooky at first sleeping here," Shakshi says. "If the walls of this tent could talk, they must have seen so much."

Photos by Gareth Phillips except where otherwise stated.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.