We should have listened to the broken teenagers

- Published

Former detective Margaret Oliver is played by Lesley Sharp in the drama Three Girls

Child sexual abuse has never been a higher police priority. But too many rapists avoid justice, argues former detective Margaret Oliver. As her role in prosecuting the Rochdale grooming gang is marked in a new TV drama, she says police must do more to win the trust of victims

I'll never forget the day I arrested Shabir. The light had begun to fade as we knocked on the door of his terraced house in Oldham one early evening back in 2011. As the safety chain rattled and the door opened, the man standing before us seemed anything but the evil predator leading a Rochdale grooming gang he was about to be exposed as.

He came quietly as we arrested him and there was no sign of the defiance and abusive outbursts that would later be seen in court. He still had the look of someone who thought he was going to get away with it.

And well he might, as many rapists like Shabir had been getting away with it for years. I'd worked with too many young victims of horrific rapes and seen cases go nowhere - even when there was solid evidence. I'd lost count of the times I had to look in the eyes of broken teenagers and explain that there was nothing I could do. The rapists who'd destroyed their lives were about to get off scot-free.

But not this time.

Actors depict victims of grooming and sexual abuse in Rochdale

Getting Shabir off the street was a big breakthrough and I was convinced he was going to be the first of many. We were close to uncovering an epidemic of child sexual abuse and there were scores of men we knew had been violently raping underage girls that were in our sights.

That we'd come this far owed a lot to the huge resources now being allocated to tackling grooming gangs (Operation Span was the biggest inquiry Greater Manchester Police were running). But, more importantly, it was down to the hard-won trust we'd managed to establish with the girls these vile rapists were targeting.

Without that trust, it didn't matter if 10,000 officers were assigned to the case. We had to get girls to give evidence in court and I knew only too well that Greater Manchester Police did not have a particularly sophisticated approach to winning vulnerable hearts and minds when trying to prosecute rapists.

Even though an awareness of child grooming was starting to sweep through the country, the police were still relying on an outdated, approach that didn't work.

Joining the police as a mum of four in 1997, I'd spent years learning how to build trust as a detective and family liaison officer working on major murders. I knew that good policing could not function without it. But the hard work of building up trust wasn't especially valued by the top brass. I wasn't breaking down doors or wrestling violent drug dealers to the ground. I was going to a cemetery to help a mother pick a plot to bury her son and supporting people who were prepared to give up everything and go on to the witness protection programme to put away murderers.

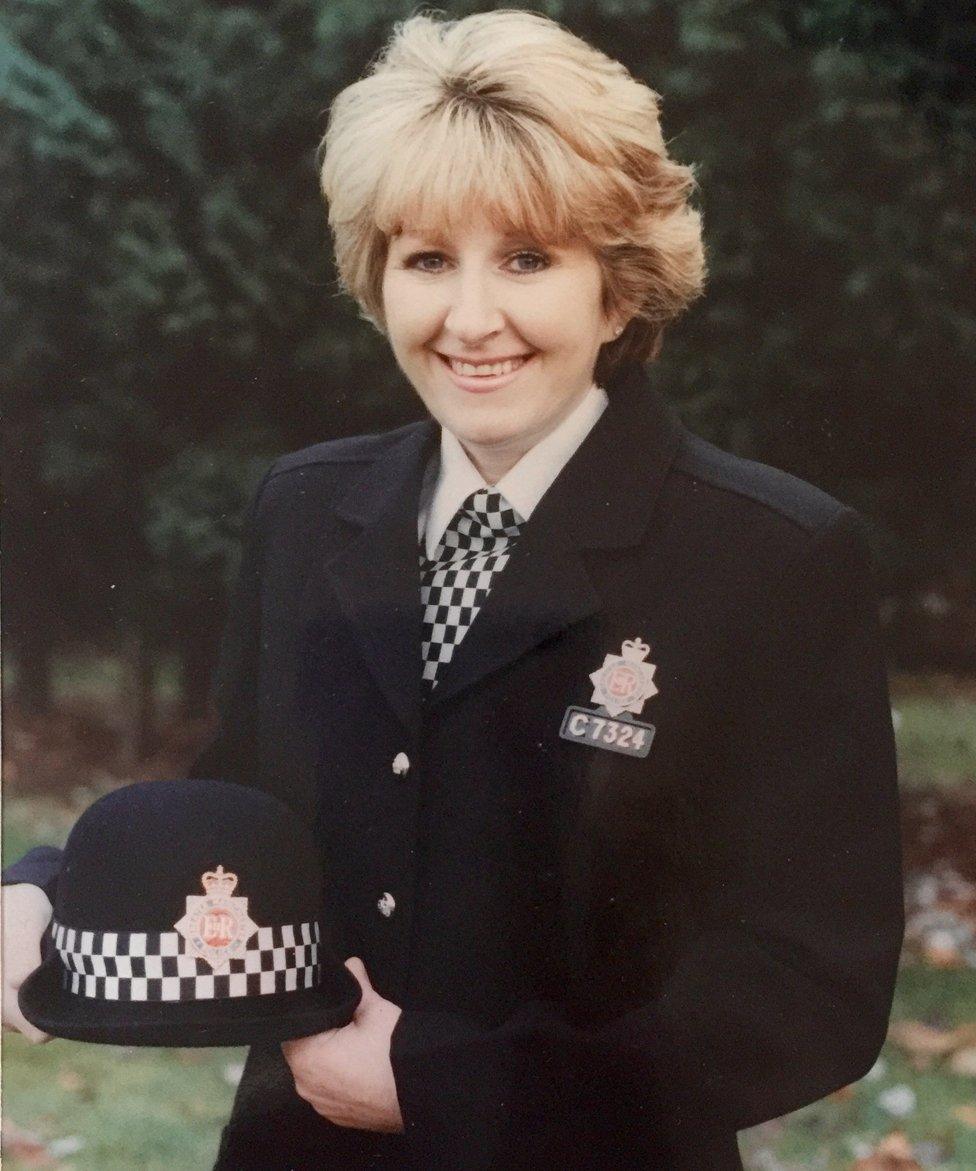

Maggie Oliver when she was a serving officer with Greater Manchester Police

It wasn't long before I was working on rapes, domestic abuse and child protection jobs - the kind of cases that other officers working in Moss Side generally didn't want to do. And I was good at them. But if you won the trust of vulnerable girls who'd been through hell, you had to deliver - and that was heavily dependent on the appetite of people at the top to investigate these crimes.

Years before I worked on a scoping exercise - a full-blown major incident team investigation which had identified considerable numbers of child abusers in south Manchester. I'd listened to girls who had been drugged so they couldn't move before they were violently raped - but the investigation was closed down. A few people were warned under the Child Abduction Act but no-one was charged.

I was sickened then and still feel angry now when I think back to that case. Vulnerable people were reaching out, desperate to secure justice, and we were letting them down. I'd sworn an oath to uphold the law and ensure "equal respect to all people" when I joined the police. Those words seemed meaningless now.

Unless we started showing respect to young girls from poorer areas, we were never going to win their trust. When Greater Manchester Police's failings in dealing with child abuse were later laid bare in a series of damning reports, one police officer gave a radio interview in which he admitted that officers referred to the girls as "scrubbers" and child prostitutes.

That was putting it lightly. I'd heard worse from other officers. There was no real effort to win their trust and a staggering lack of empathy. Some police officers wouldn't even come into the houses where the girls lived. They'd sit in the car eating sandwiches waiting for me to come back. When we drove girls to the station and they asked to put Radio 1 on, officers would switch to Radio 4. There was no attempt to make them feel comfortable. But it's these little things that often count, and which help to build bridges.

I saw myself as a person first and police officer second, but many of my colleagues could only see themselves as police officers first and foremost. Empathy had been trained out of them. The pressures of modern policing and a target-driven culture was driving humanity out of our profession. I couldn't do the job if I didn't care, but to show a human face was a sign of weakness to some. "You've become emotionally involved," they'd say. We had to maintain too big a distance from everyone. As a result, there were many estates where the police were hated. The people who lived there suffered disproportionately from crime, but had given up on the police. They didn't trust us because we showed them no respect.

It's this failure to win the trust of victims of appalling crimes that's at the heart of the BBC drama about the Rochdale grooming scandal. It shows a desperately real side of policing that's rarely ever dramatised and the general public know little about.

In the end Shabir and 11 other men were convicted for child abuse in 2012. But this was just the tip of the iceberg. There were many, many more who got away with it and I was left with the sense that this was a box the police didn't really want to open. But they couldn't keep the lid down for long and now the secret is out. A crime that had been contained and swept under the carpet for years can no longer be ignored.

For me, the end of the road was when they betrayed the trust I'd earned from a key witness and I couldn't get assurances on how vulnerable witnesses would be treated in the future. I knew men who'd violently abused girls were still walking the streets and we had the power to stop them. I couldn't do a job I loved as long as I knew rapists were getting away with it because police viewed the girls they preyed upon as unreliable witnesses. The criminals knew this and they were emboldened by it.

"No one will believe you," they'd laugh at sobbing girls, as they left them crushed in a heap on the floor.

Maxine Peake - who plays local sexual health worker Sara Rowbotham - with Lesley Sharp

Barely a week goes by these days without a headline referring to a crisis in the police. But the crisis no-one's talking about is the crisis of trust, particularly where young people are concerned. A few years ago, an all-party group of MPs found that a significant proportion of children and young people have a profound lack of trust in the police. It should have acted as a wake-up call, but I don't believe things are getting any better.

When the human side of the police is shown, we always break down barriers and there are plenty of shining examples of brilliant police officers who do this week in week out. But we need more and we need leaders who set a culture in place who insist the values of empathy, honesty and integrity are always upheld in our dealings with vulnerable victims. If we can't reach out to vulnerable witnesses, all the announcements from Westminster won't mean a thing. Criminals will keep getting away with it.

Watch Three Girls at 9pm on Tuesday 16 May 2017 on BBC One

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.