Treating children with electroconvulsive therapy

- Published

Electroconvulsive therapy - in which a small electric current is passed through the brain causing a seizure - is now used much less often than it was in the middle of the last century. But controversially it is now being used in the US and some other countries as a treatment for children who exhibit severe, self-injuring behaviour.

Seventeen-year-old Jonah Lutz is severely autistic. He's also prone to outbursts of violent behaviour, in which he sometimes hits himself repeatedly.

His mother, Amy, is convinced that if it wasn't for electroconvulsive therapy - ECT - he would now have to be permanently institutionalised for his own safety, and the safety of those around him.

The use of ECT featured famously in the 1975 Hollywood movie, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, starring Jack Nicholson. Set in a mental institution, the Oscar-winning film cemented most people's view of ECT as barbaric.

But Amy describes the modern version of the therapy as little short of miraculous.

"ECT has been transformative for Jonah's life and for our life," she says. "We went for a period of time - for years and years - where Jonah was raging, often multiple times a day, ferociously. The only reason he's able to be at home with us, is because of ECT."

It's estimated that one in 10 severely autistic children like Jonah violently attack themselves, often causing serious injuries ranging from broken noses to detached retinas. No-one really knows why. Some theories link self-injuring behaviour to anxiety caused by an overload of sensory signals, others to frustration as the autistic child struggles to communicate.

Amy and husband Andy tried countless traditional treatments using medication or behavioural therapy before finally turning to ECT - a treatment that first began to be used on children like Jonah a decade ago, in parts of the US. Each session alleviates his symptoms for up to 10 days at a time - but it's not a cure.

Jonah's doctor, Charles Kellner, ECT director at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, is so convinced it's effective and safe that he allows Amy to witness the procedure and the BBC to film it.

Prof Kellner says the best way to overcome the negative image of ECT portrayed in popular culture is "to show people what modern ECT is really like, and show them the results with patients like Jonah".

Jonah is one of a few hundred children in the US to receive the controversial treatment. He has had about 260 ECT sessions since the age of 11.

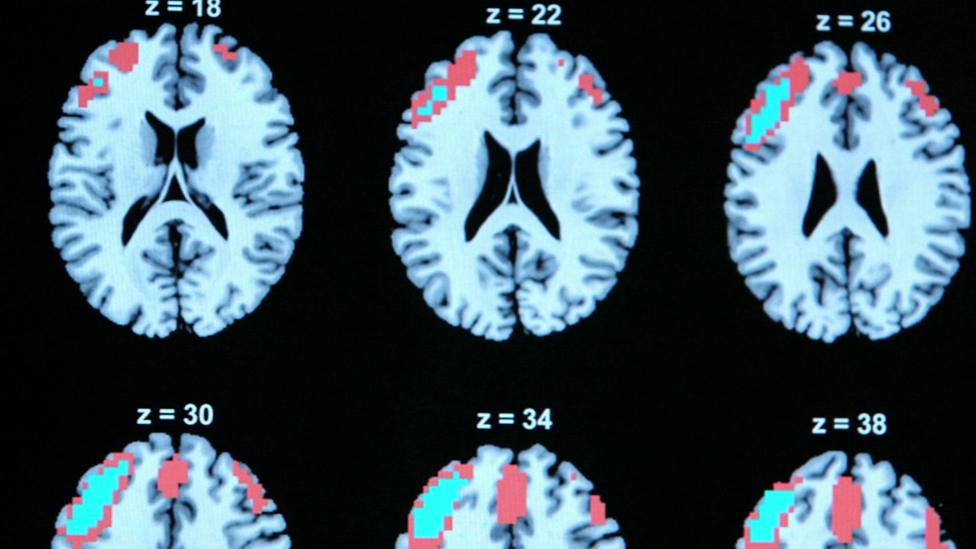

"There's a lot of interesting new neural imaging research showing that ECT actually reverses some of the brain problems in the major psychiatric illnesses," Kellner explains, as he makes final checks on the wiring around Jonah's temples.

"We don't know exactly why it works in people with autism and superimposed mood disorders, but we think it probably reregulates the circuits in the brain that are deregulated because of autism."

The modern treatment is carried out under general anaesthetic, with muscle relaxants to prevent violent convulsions. At the flick of a switch, Kellner administers just under an amp of electric current in a series of very short pulses.

Jonah's body begins to shake as the current induces a seizure - ECT specialists think this may "reset" the malfunctioning brain. The convulsions last for about 30 seconds.

Amy is unperturbed by what she sees.

"If a doctor says they need to cut open your child's chest to conduct life-saving surgery, you would allow it. That is more barbaric yet we accept it," she says.

Within an hour Jonah is fully alert. He and his mother head out of the hospital and on to the New York street to find an ice cream parlour.

Find out more

Viewers in the UK can watch Chris Rogers's Our World documentary My Child, ECT, and Me on the BBC News Channel on Saturday 20 May or Sunday 21 May - click here for transmission times or to watch online

Viewers outside the UK can watch it on BBC World News over the coming week - click here for transmission times

Because the long-term effects of ECT on children exhibiting self-injuring behaviour are unknown, in some countries - and in a handful of US states - the treatment is not allowed. The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence doesn't recommend ECT for use on under 18s.

But ECT is a well-established treatment in adults for severe, often life-threatening depression. Its use is controversial, though, with memory loss the main acknowledged side-effect. What's disputed is the scale of the memory loss. Studies carried out by ECT doctors suggest lapses are mostly short-term and that memory function soon returns to normal. But opponents of ECT cite surveys claiming to show that more than half of patients suffer serious long-term memory loss.

"It's a traumatic brain injury," says Dr Peter Breggin, a psychiatrist who has long fought the psychiatric establishment, and campaigns for a total ban on ECT. "The electricity not only travels through the frontal lobes - that's the seat of intelligence, and thoughtfulness and creativity and judgment - it also goes through the temporal lobes - the seat of memory. You are damaging the very expression of the personality, the character, the individuality, and even, if you believe in it, the expression of the soul."

For former US Army intelligence officer Chad Calvaresi and his wife Kaci, the potential benefits of ECT far outweigh the risks for their 11-year-old, violently autistic daughter, Sofija.

"When she was aggressing towards me, my instinct as a mom was to grab her and hold her and hug her and wait," Kaci explains. "But she got so big and strong that I couldn't do that."

Sofija spent much of her early life suffering neglect and abuse in a Serbian orphanage, before Chad and Kaci adopted her in 2009. They were determined to give her a better life in America, but in 2016 they suffered the heartbreak of institutionalising her again - this time for her own safety.

"She beat herself so bad her nose was busted and bleeding, her lips were busted open and bleeding," Chad explains. "She gave herself a black eye. I was scared of my own daughter."

For six months Sofija received medication and therapy as an in-patient at the renowned Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, but there was little improvement. During her frequent violent episodes it often took three highly trained care staff - all wearing protective clothing and shielding Sofija with padded mats - to prevent her injuring herself or others.

After exhausting all other options, Sofija's doctors finally agreed to Chad and Kaci's request to give her ECT. Just a month later her behaviour had improved enough for her to return home.

We caught up with the family after six months and more than 30 treatments, and the transformation was remarkable. Sofija was swimming in the family pool and playing with her siblings, and while her violent episodes hadn't disappeared completely, her parents felt they were less intense and more manageable. Sofija was also receiving home schooling in maths and English. "She's sharp as a tack," says Kaci. "The only memory loss that Sofija has had from ECT is she forgets the procedure has actually happened."

ECT for severely self-injuring autistic children like Sofija is still in very limited use, and without a long-term scientific study it remains highly controversial. But even though Sofija is likely to need ECT every week for the foreseeable future, her parents have no regrets - they have their daughter back home.

"It's overwhelming if I think about it," says Kaci, "but what future did she have without it? My hope is she doesn't need it for the rest of her life but at this point I see it like a diabetic needing insulin. It keeps her alive. Literally it keeps her alive and it makes it possible for us to be able to have her in our home living life with our family and enjoying Sofija."

Sofija enjoys a maths lesson at home

For and against ECT

The Royal College of Psychiatrists says ECT is a "safe and effective treatment for severe depression" in adults but acknowledges on its website, external that some dispute this:

For

Many doctors and nurses will say that they have seen ECT relieve very severe depressive illnesses when other treatments have failed. Bearing in mind that 15% of people with severe depression will kill themselves, they feel that ECT has saved patients' lives, and therefore the overall benefits are greater than the risks. Some people who have had ECT will agree, and may even ask for it if they find themselves becoming depressed again.

Against

Some see ECT as a treatment that belongs to the past. They say that the side-effects are severe and that psychiatrists have, either accidentally or deliberately, ignored how severe they can be. They say that ECT permanently damages both the brain and the mind, and if it does work at all, does so in a way that is ultimately harmful for the patient. Some would want to see it banned.

You can watch the Our World documentary "My Child, ECT and Me" at 21:30 on Sunday on the BBC News Channel, on BBC World at these times and on the BBC iPlayer.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.